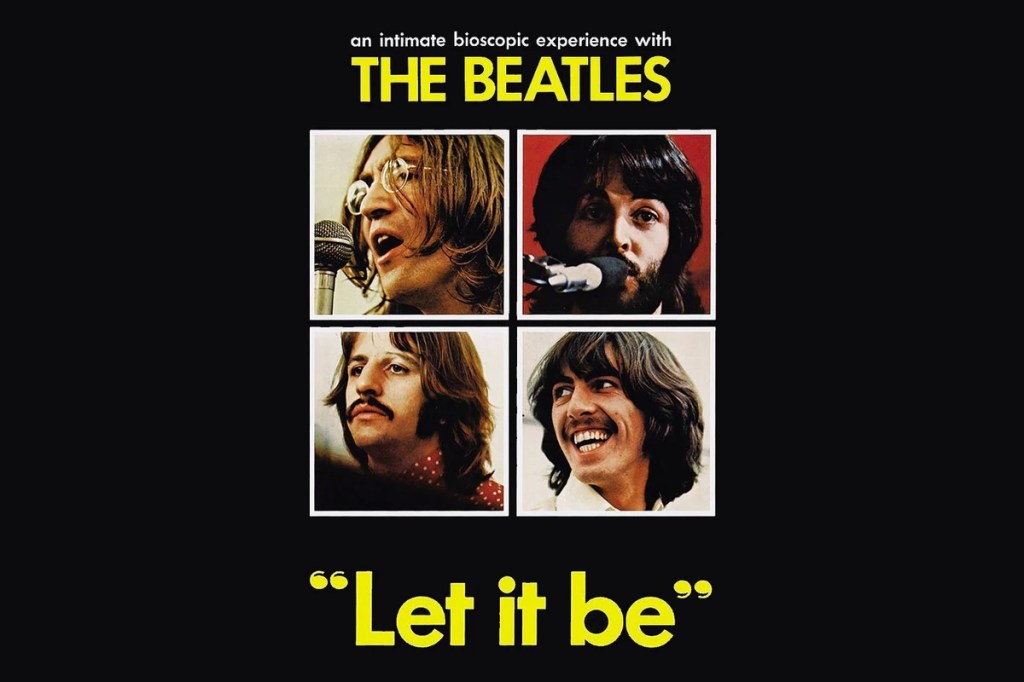

Continuing (after too long a gap!) my Beatles retrospective, I look at the curious case of Let It Be.

Watching Let It Be (1970) today is an odd experience. The oddity lies not so much in the actual movie as the imbalance between the movie and the wealth of associated stories, supplementary materials, and interpretations that have overshadowed it over the years.

Let It Be originated in the winter of 1969 as a rather vague attempt by a film crew, led by American director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, to do a documentary on the Beatles rehearsing for a concert that would serve as the movie’s finale. Two key difficulties arose, though:

First, the band had no definite plans to perform in a concert, which made the whole enterprise uncertain and improvisational.

Second, Lindsay-Hogg and his crew were catching the Beatles at an especially fractious moment in their careers. The Beatles bickered over their music and the direction the movie ought to take, tempers flared, and at one point George Harrison even temporarily quit the group.

The filmmakers shot hours upon hours of footage that they eventually edited down into a short, 80-minute documentary completed more than a year later. Let It Be was released in theaters in May 1970, about a month after the Beatles broke up. The movie thus ended up unintentionally being a kind of melancholy retrospective on the now-shattered group.

The movie subsequently received videotape and laser disc releases. It was not released—and still has not been released—to DVD, though, and became progressively harder to find as the years passed. For a while, Let It Be seemed on the path to becoming a piece of lost media.

The efforts of Lindsay-Hogg and his crew were far from forgotten, though. The makers of the 1990s Beatles Anthology TV series mined some of the 1969 footage, including both material used and not used in the final movie, to tell the story of that period in the band’s life. The dominant theme of the material presented, as well as the recollections by the surviving Beatles, was how contentious and unpleasant the experience of making the documentary was.

Over 25 years after that, the footage from 1969, now with gorgeously restored visuals and sound, served as the source material for Peter Jackson’s Get Back. An epic, nine-hour-long series, Get Back reconstructed on a day-to-day basis all the Beatles’ ups and downs during the time when the crew was filming them. Get Back presented a more balanced picture of that period than the Anthology, showing the many arguments and divisions within the band over the weeks of filming, but also the good times when they came together to make great music.

Not content with giving us Get Back, though, Peter Jackson and his technical wizards ultimately restored Let It Be as well. The newly revamped documentary received a new release on the Disney+ streaming service in 2024.

After almost 60 years and such a convoluted history, what are we to make of the movie that started it all? How does Let It Be come across today?

Watching the movie brought a couple surprises for me. I was struck by how simple and seemingly artless it was. In contrast to many other documentaries, including Beatles documentaries such as the Anthology, Get Back, Eight Days a Week, or Beatles ’64, Let It Be has no narration, no interviews with participants or outside commentators, not even captions or title cards.

Instead, Let It Be opens with Mal Evans and others setting up the Beatles’ instruments and other equipment while Michael Lindsay-Hogg and his film crew assemble nearby. The movie then proceeds to show us various short scenes of the Beatles playing music, talking, or goofing around. Associated players such as Yoko Ono, Linda Eastman, or George Martin drift in and out during these scenes.

Roughly a third of the way through, the action shifts from the original set up at Twickenham film studios to a studio at Apple headquarters. Here the Beatles are joined for their jam sessions by keyboardist Billy Preston. Over the course of these scenes at Twickenham and Apple, we hear the Beatles perform all the songs that would eventually be featured on the album Let It Be, as well as a few songs that ended up on Abbey Road and various covers of non-Beatles songs.

Through all this, we get no explanations or context for what is happening on screen. The overall effect is like watching someone’s home movies, albeit professionally shot and lovingly restored ones.

The other notable surprise is how placid and generally conflict-free the movie is. After the decades of hearing about how miserable the filming experience was and how the band was falling apart, it is faintly shocking how little evidence of that turns up on screen. George may have quit the group during filming, but you would never know that from watching Let It Be.

The closest the movie ever gets to showing divisions within the group is one infamous scene in which George and Paul argue about George’s guitar playing. Perhaps another example would be a later scene when Paul complains to John about how their rehearsing and the accompanying filming do not seem to be going anywhere. Otherwise, we get no indications that anything was awry with the group.

(The paradox here is that Jackson’s Get Back, because of all its scenes of collaboration and camaraderie among the Beatles, has been credited with debunking the notion that they were all at each other’s throats at this time. In fact, though, Get Back contains far more scenes of conflict within the band than Let It Be.)

Neither the film’s simplicity or selectively positive portrayal of the band’s life make Let It Be a bad movie, though. For Beatles fans, there is a lot to enjoy here.

Even in the later, more strained period of their careers, few people could be as effortlessly charming and charismatic as the Beatles. It’s always fun to watch them play music and kid around: consider the over-the-top way John and Paul rehearse “Two of Us,” with heavy mugging and silly voices thrown in for good measure. We also get quieter clowning, as when Paul and Ringo play the piano together.

Some memorable incidents arise from the presence of loved ones in the studios. At one point, John and Yoko waltz around Twickenham while the other three Beatles play George’s song “I Me Mine.” When Linda and her daughter Heather arrive at Apple, the movie presents cute moments of the Beatles playing with Heather. At one point, she and Paul make noises into a microphone; at another, Heather hits one of Ringo’s cymbals and he reacts with mock surprise.

Such rambling scenes give us glimpses into the Beatles’ creative process circa the late 1960s. By this phase of their careers, the days when George Martin would make them record an entire album in a day were long gone. Composition was a lengthy process of trial-and-error that might eventually produce a song.

The journalist Hunter Davies, in his excellent book on the group, chronicled the curious stop-start process of songwriting during the making of Sgt Pepper. John and Paul’s composition of “With a Little Help from My Friends” involved a long time banging away on the guitar and piano as they tried to identify worthwhile bits and write apt lyrics. The process would be broken up by breaks to play other, non-Beatles music; smoke marijuana; or conduct other business.

Davies quoted George on how they worked in those days:

[W]e haven’t got a clue about what we’re doing to do. We have to start from scratch, thrashing it out in the studio, doing it the hard way. If Paul has written a song, he comes into the studio with it in his head. It’s very hard for him to give it to us and for us to get it. When we suggest something, it might not be what he wants because he hasn’t got it in his head. So it takes a long time. Nobody knows what the tunes sound like till we’ve recorded them, then listen to them afterwards.

Let It Be shows us this process unfold on camera (as does Jackson’s Get Back, at even greater length). While often slow and arduous, the composition process also leads to dazzling moments. One of the highlights of the movie is when Ringo and George work together, on guitar and piano, to hone the song that would become Ringo’s “Octopus’ Garden.”

To watch musicians brainstorm and experiment and then gradually to hear a familiar, beloved song emerge as a result is a wonder to behold. Get Back has a similarly indelible sequence built around the title song. The work is mundane and laborious yet tinged with the miraculous. The fact George Martin joins in the composition of “Octopus’ Garden” with some light scatting to the song just adds to the joy of the experience.

Watching the Beatles work also means we get to hear lots of great music in the movie. Let It Be of course includes a performance of the title song, Paul’s soaring, soulful anthem featuring a guitar solo from George that (as numerous scientific studies have proved) is one of the greatest guitar solos of all time.

We also get “The Long and Winding Road,” Paul’s wistful ballad that, being performed live, is free from all the bells-and-whistles Phil Spector added to the album version. Other songs include Paul and John’s back-and-forth “I’ve Got a Feeling”; John’s passionate love song/plea “Don’t Let Me Down,”; and “Get Back,” with its infectious, driving rhythm.

Credit should go to Lindsay-Hogg and editors Tony Lenny and Graham Gilding for how they crafted this material. While Let It Be lacks a tight structure or larger context, the filmmakers did make some creative choices that give the movie a rough narrative.

The early scenes at Twickenham and later Apple are entertaining but, as the movie goes on, a general sense of aimlessness sets in. By the time the band is playing “Bésame Mucho” with Billy Preston and Paul is complaining to John about how they are not getting anywhere, the viewer shares Paul’s sentiment. Where is all this going?

Then, the movie reaches a turning point with, appropriately enough, the performance of “Let It Be.” The loose, almost cinema verité-style of the earlier scenes gives way to a more assured, polished style: Paul sings directly into the camera; we cut to shots of George, John, and Ringo during their parts; we get insert shots of Paul’s hands on the piano or Ringo’s cymbals clanging; and so on. The overall impression is of the band now gaining renewed confidence. This more confident style continues through subsequent performances.

The movie soon moves to its climax, the Beatles’ iconic concert along with Preston on the rooftop of Apple headquarters. The previous listlessness and irritability is gone: the four Beatles are now playing with enthusiasm, grinning at each other as in the glory days of the past.

As they play their set, the movie cross-cuts to the reactions of ordinary Londoners, on the street or on adjacent rooftops, to this impromptu concert by the world’s most famous musicians. Reactions vary from excitement to irritation to bemusement. My favorite moment is the dry comment of a passing vicar who says, “Nice to have something free in this country at the moment, isn’t it?”

The contrast of the performance on the rooftop with reactions on the ground also leads to genuine dramatic suspense. London police respond to complaints about the noise. The movie shows us police officers coming to Apple headquarters and going up onto the roof with the intent of shutting down the performance.

When the police arrive, the Beatles, who are beginning a reprise of “Get Back,” briefly hesitate. Then, sensing that this is the perfect moment they and the filmmakers have been waiting for, they opt to defy the police. George cranks up the amp, and they finish the song. Paul in particular has a ball with the moment, throwing in new lyrics such as “You’ve been playing on the roofs again!…Your mommy doesn’t like that!…She’s gonna have you arrested!”

The band finishes the song and then, presumably not wanting to push their luck, wraps up the performance. John provides the sign-off line: “I’d like to say ‘thank you’ on behalf of the group and ourselves, and I hope we’ve passed the audition.” And with that, Let It Be ends. The whole sequence is a blast.

Viewed with a fresh eye almost 60 years later, Let It Be is not a great movie, but it is a good one. The documentary offers an memorable snapshot of the Beatles toward the end of their time working together as a group. It shows how, even when the band was approaching its breaking point, the four musicians could still create amazing songs.

In the end, I think the verdict must be that Michael Lindsay-Hogg and his team succeeded in doing just what they intended to do. They made a movie about the Beatles rehearsing for a concert that they then performed at the end. Moreover, Let It Be captured on film, in that rooftop concert, the last time the band would ever perform together in public. That is no mean accomplishment for a movie.