Next in my Zhang Yimou retrospective, I look at the visually distinctive Shadow.

Watching Shadow (2018), I was reminded of someone playing an elaborate game with dominoes. Like a domino master, Zhang Yimou and his co-screenwriter Li Wei set up their characters and plot through a long period of painstaking preparation, before they then start everything tumbling down in a spectacular fashion. Also, dominoes’ signature color of black and white plays a prominent role in the movie.

Adapted from an earlier screenplay by Zhu Sujin, Shadow is set in the ancient kingdom of Pei. The young king (Zheng Kai), who comes across as a spoiled weakling, aspires to establish peace with the rival kingdom of Yan. Others are not pleased with the king or his plans, though: his willful younger sister (Guan Xiaotong) resents his interference, and the army wants to make war on Yan kingdom.

The king’s most important opponent, though, is the Commander (Deng Chao), the leader of the armed forces. Having once lost a duel to his counterpart in the Yan kingdom, General Yang (Hu Jun), the Commander is eager for revenge. As the movie opens, the Commander has challenged General Yang to a re-match, in defiance of the king’s wishes.

As soon becomes apparent, though, little in Pei is as it seems. Early in the movie, we learn that the man who presents himself as the Commander is in fact an imposter named Jing. The previous duel with General Yang injured the Commander so grievously that he has been wasting away ever since. The ailing real Commander (also played by Deng Chao) has therefore recruited a lookalike, or “Shadow,” to take his place in public.

The real Commander is secretly training Jing to fight General Yang in the next duel. In this training he is aided by his wife (Sun Li), who is skilled in martial arts that employ the improbable weapon of an umbrella.

If he can master this “feminine” fighting style and defeat Yang in combat, Jing can give up pretending to be the Commander and return home to his beloved mother.

Some obstacles may lie in the way of this happy resolution, however. We are given hints that the real Commander is not being entirely honest about what his true plans are. Also, Jing and the Commander’s wife may be developing feelings for each other.

If all this seems complicated, then believe me that the summary above only scratches the surface. Everyone in Shadow turns out to be following a distinct agenda, and the movie ultimately serves up enough plot twists, reversals, and betrayals to fill an entire season of prestige television.

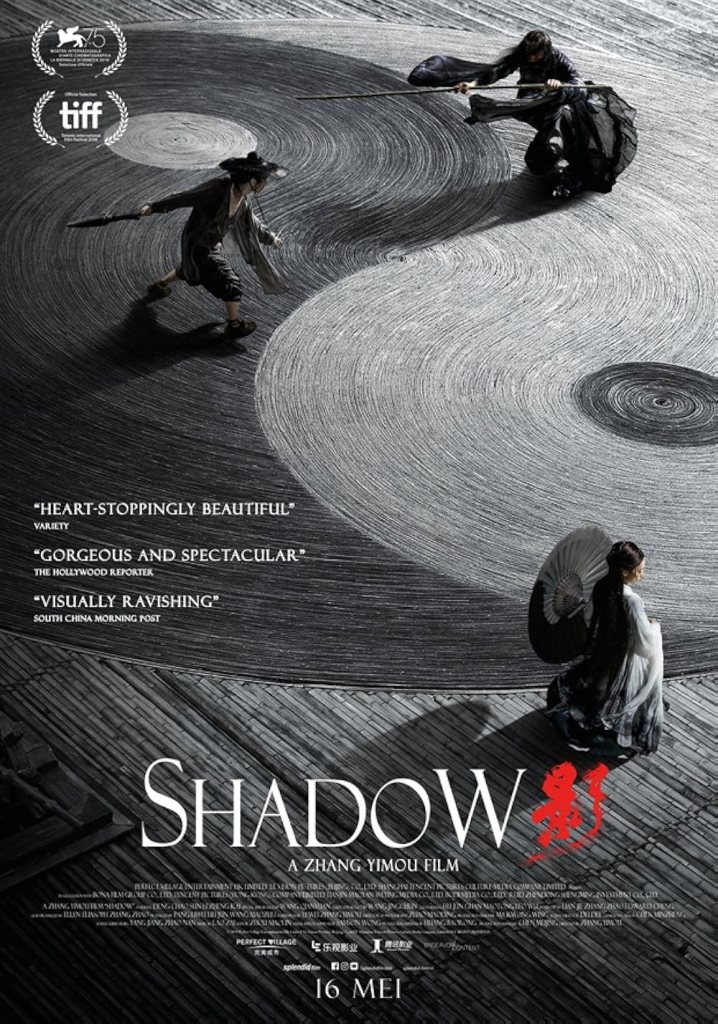

In telling this story of palace intrigue, Zhang, his veteran cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding, production designer Kwong Wing Ma, and costume designer Chen Minzheng have adopted a highly unusual visual style. Known as a maestro of red and other vivid colors, Zhang has made the bold artistic choice here of limiting his color palette to black, white, and gray. Everything in Shadow, from the landscapes, to the sets, to the characters’ costumes, are rendered in some shade of these three colors.

The king’s palace and other interiors are black and gray stone offset by screens that display either silvery murals or rolls of snow-white paper etched in dark black ink (as the king explains, the latter display his “Ode to Peace”). Outdoor scenes feature slate-gray mountains and washed-out trees under a canopy of perpetual rain. Court members’ robes are decorated with varying patterns, strokes, and squiggles of black against lighter backgrounds, although Jing and the Commander’s wife sometimes dress entirely in white.

Different visual motifs echo the black-gray-white color scheme: the endless rain, uses of smoke, and the ways characters are glimpsed through the gauzy screens. Above all, there are the repeated yin-yang symbols that turn up in the movie, as on a board used to tell fortunes or the floor of a cavern where the Commander and his wife teach Jing the ways of combat.

Along with the color choices, Zhang gets visual interest from the layout of sets such as the king’s palace and the Commander’s home. As designed by Kwong, the palace recalls the labyrinth of the house in Raise the Red Lantern. Characters constantly weave their way through chambers and bric-a-brac or slip away into the cavernous secret room beneath the Commander’s house.

All these details enhance the overall sense of a murky, twilight world that must be carefully navigated, in which nothing is clear and no one can be wholly honest or trusting with each other.

If the treatment of color is Shadow’s most memorable feature, its second-most memorable is the wuxia-style action that dominates the final third or so of the movie. Both the eventual re-match duel between Jing and General Yang and a battle between armies are inventively staged set-pieces (you will never look at an umbrella the same way again after these sequences). The movie’s final scene, while not as creative, still contains some surprises, as well as a body count that Shakespeare would envy.

If the visual style and action are Shadow’s greatest strengths, the movie also has its weaknesses. The most significant problem is the pacing. To return to the domino analogy, the first two-thirds of Shadow are devoted to setting up the pieces, which is a markedly less entertaining process than seeing them all fall into place later. The viewer must sit through a lot of dialogue-heavy scenes in which the characters’ various schemes are explained before getting to the fun stuff. During these early passages, I found myself feeling a bit bored and sometimes confused by all the plot machinations.

A more ambiguous issue with Shadow is the characters. Few of them are sympathetic and none of them are very well developed. All have a couple basic characteristics that they repeatedly display: Jing longs to return home but maintains a stoic front; the Commander is bitter and vindictive; his wife is sadly dignified; the king is selfish and petulant; his sister is callow and spirited, etc.

Zhang has made other movies with minimal characterization, with varying degrees of success. Hero triumphed because its emotionally distant characters came across as larger-than-life, like figures from a myth. Curse of the Golden Flower stumbled because its palace intriguers came across not as mythic but merely as nasty people.

In my judgment, Shadow falls somewhere between these other two movies in its approach to the characters. The various members of the Pei court are not as charismatic as Hero’s warriors. Nevertheless, the stylized way they are presented (as underlined by the fact that most of them do not even have proper names) make them feel like they stepped out of a fairy tale. Their artificial quality takes the edge off their far-from-admirable behavior.

Also, special credit should go to Deng Chao and the movie’s makeup team for the dual role of Jing and the Commander. While neither character is complex, Deng’s appearance and behavior in each role is so different that I often forgot they were played by the same actor.

Overall, Shadow is a visually impressive movie that is not very involving for much of its run time but boasts a gripping, action-packed climax. Although far from Zhang’s best movie, it still demonstrates the extraordinary technical skill of the director and his team.