Next in my Beatles retrospective, I look at two documentaries that get back to when the Fab Four first hit it big.

Following the release of Yellow Submarine, the Beatles went on to participate in a documentary that ultimately became the film Let It Be. This would be the final film they participated in while the band was still together.

I will review Let It Be, but before I look at that movie, I want to take a step back in the band’s history by looking at two other documentaries that chronicle the Beatles’ career. Before remembering the band’s later era, when the relationships among the four musicians were fraying, it seems appropriate first to remember the early era, when the bonds were at their strongest.

Two documentaries that cover this early period are The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years (2016) and Beatles ’64 (2024). Eight Days a Week, directed by Ron Howard and written by Mark Monroe and P. G. Morgan, covers the Beatles’ careers from 1963, when they first became famous in Britain, to 1966, when they stopped performing live shows. Beatles ’64, directed by David Tedeschi (no writer is credited), has a narrower focus, looking exclusively at the Beatles’ first, pivotal 1964 tour of the United States.

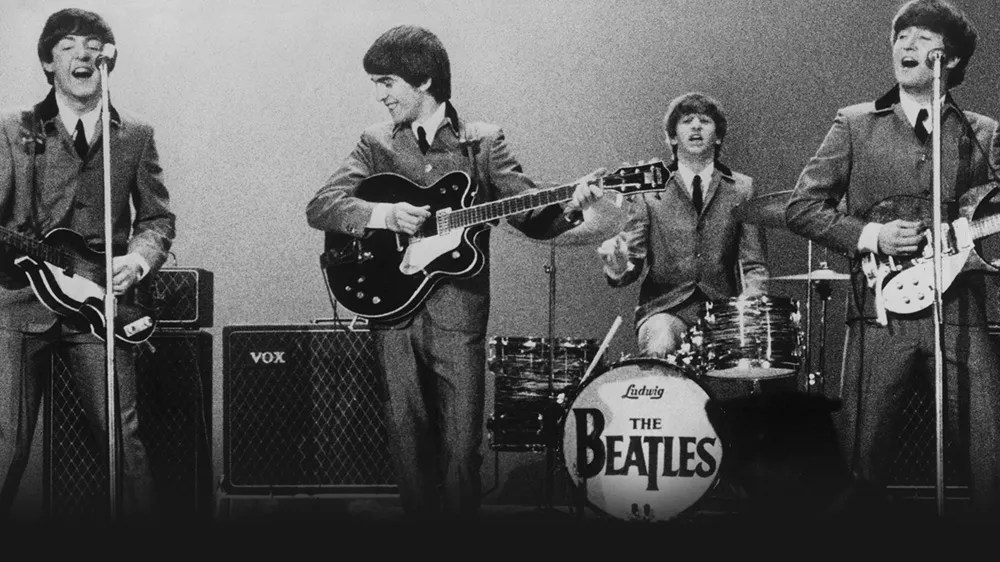

The two films are quite similar in their approach to the material and filmmaking style. Both unfold in a straightforward, chronological way: Eight Days a Week begins with the Beatles hitting it big with their first album, Please Please Me and ends with their final 1966 concert and the recording of Sergeant Pepper. Beatles ’64 begins with the group’s arrival in New York and first Ed Sullivan show performance and proceeds through the stop in Washington, DC, to the final Ed Sullivan performance in Miami.

Both documentaries draw on period footage of the Beatles, either performing, rehearsing, or during downtimes; and of their many ecstatic fans. Beatles ’64 relies heavily on film shot by documentarian brothers David and Albert Maysles during the band’s first American tour, and Eight Days a Week also draws on the Maysles’ work.

Both documentaries intersperse the older footage with interviews. These include new interviews with Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr and archival interviews with John Lennon and George Harrison. People close to the Beatles, such as Neil Aspinall, Richard Lester, or journalist Larry Kane, who covered the Beatles’ extensively during their touring years, also appear.

Both documentaries balance out such “insider” perspectives with interviews of an eclectic array of acquaintances and fans who reminisce about their early experiences of the Beatles.

Eight Days a Week features interviews with Whoopi Goldberg, Sigourney Weaver, Elvis Costello, Eddie Izzard, and comedy writer Richard Curtis, as well as composer Howard Goodall, who analyzes the band’s music.

Beatles ’64 leans more into interviewing other musicians, such as Smokey Robinson, Ronnie Spector, and Ronald Isley, as well as fans such as Jamie Bernstein (Leonard Bernstein’s daughter), writer Joe Queenan, and music producer Jack Douglas.

Both documentaries also handle their subject matter in a way I would describe as affectionate and superficial. The filmmakers clearly love the Beatles and have made films meant to please fellow fans who want to watch the musicians play their early songs and to experience vicariously the thrill of Beatlemania. Neither movie delves too deeply into the technical side of the Beatles’ music or the four musicians’ relationships or the band’s historical significance, although both movies touch on these topics.

The bottom line is that a dedicated Beatles fan will not find much that is new or unexpected in either Eight Days a Week or Beatles ’64. Such a fan can still watch both movies and have an enjoyable time—at least, this fan did.

Because the two movies are so similar, I will not attempt to review each one individually but will just offer some thoughts about what stood out to me about the tale they (collectively) tell and then give an assessment of how they compare overall.

Some common themes emerge across Eights Days a Week and Beatles ’64:

Exuberance: If any word summed up the Beatles’ early career, it would be “fun.” Their songs in this period might not have been as musically sophisticated as their later work, but they were infectiously joyful. This spirit is on display in the documentaries through performance footage of “She Loves You,” “Twist and Shout,” “All My Loving,” “I Saw Her Standing There,” “From Me to You,” and other numbers.

This spirit is also reflected in the ecstasy of the Beatles’ teenage fans. We repeatedly are presented with the sight, familiar from A Hard Day’s Night and innumerable previous documentaries, of crowds of fans, mostly young women, at the concerts. We see them grinning, shrieking, trembling, weeping, snapping photos, and mouthing along to the lyrics. We learn how in November 1963 the queue of fans waiting for tickets to see the group stretched for a mile in Liverpool.

We also get interviews, conducted by the Maysles or contemporary news crews, of fans clustered outside the Beatles’ hotel in New York or other Beatle-adjacent venues. The fan love of the group expressed in these interviews is as ardent and often scarcely less ecstatic as what is expressed at the concerts.

An American female fan declares “I love the Beatles…and I’ll always love ‘em,” adding that even when she is “105 and an old grandmother, I’ll love ‘em.” She also throws in the personal message to Paul: “Adrienne from Brooklyn loves you with all her heart.” Another fan opines “Ringo has a sexy nose.” Still another comments, “George has got sexy eyelashes.”

One fan rattles off the gifts she and her friends have collected for the Fab Four: “George likes to relax, so we bought him a pillow; and Paul likes to sketch and paint, so we bought him a sketch pad with charcoal; we bought John an ID…we bought Ringo two science fiction books.” (Amid this litany, one member of the group interjects: “You didn’t chip in for it, Alice!”)

The most direct comment comes from one young interviewee who is asked “What do you love about the Beatles?” In reply, she screams, “EVERYTHING!”

Vickie Brenna-Costa, who was among the fans gathered outside the Beatles’ hotel in New York during their first American tour, is interviewed in Beatles ’64. Looking back, she describes her and her fellows’ sentiments: “It was a crazy love…Why we were [in a] screaming frenzy? I can’t really understand it now. But then, it was natural. It was a natural thing to do.”

Race: Rock n’ roll is an art form that originated among Black Americans but that white musicians such as Elvis Presley and the Beatles rode to tremendous success. Moreover, the Beatles’ rise to fame overlapped with one of the most intense periods in Black Americans’ struggle for equal rights. This complicated historical mixture of race and music is acknowledged in both documentaries, although both also avoid delving too deeply into the topic lest anything overly sensitive or contentious come up.

Smokey Robinson reminiscences about meeting the Beatles during their pre-fame Cavern Club-era, when he and the Miracles were on a tour of Britain. “They got my attention,” he comments. “They were playing music that you were familiar with…they were between rock and pop and rhythm and blues, all together.”

Of the Beatles later covering his song, “You Really Got a Hold on Me,” Robinson is gracious: “To have somebody like the Beatles…to take one of my songs and record it, I can’t beat that as a songwriter.”

Ronald Isley also expresses pleasure at having the Isley Brothers’ “Twist and Shout” covered by the Beatles. “We were so glad. It was great for us.” However, he wryly adds, “We were kind of wondering, ‘Why couldn’t we be on some of the shows that they were on?’…We should have been on the Ed Sullivan Show.”

Alongside the commentaries from Black musicians, Beatles ‘64 has archival footage of Black New Yorkers interviewed about the newly arrived Beatles. Reactions are tepid. One man politely says, “I think they’re very nice. Very nice…They’re original.” An elementary school-aged girl says, “I guess they’re OK.”

A Black record store patron is blunter: “I think they’re disgusting, myself…Every time I turn on the radio…it seems like that’s all I hear is the Beatles.” The patron’s tastes run in a different direction, with his favorites being the Miles Davis Quartet and John Coltrane Quartet.

The relative indifference of Black listeners had its advantages, though, as an anecdote in Beatles ’64 illustrates. Ronnie Spector recalls how she took the group out to eat in Harlem, where, to their great relief, no one recognized them. At the barbeque place they went, Spector describes, “The Black guys are eating their ribs…And nobody paid them any attention. And it was great. They loved that.”

Even across the racial divide, though, certain demographics are reliably pro-Beatles. Asked about the band, a group of Black teenage girls wax enthusiastic (“Oh, I love them. They’re great!” “They deserve all this!”) in tones similar to their white counterparts.

Echoing this enthusiasm, Whoopi Goldberg explains in Eight Days a Week how her love for the Beatles transcended the obvious differences: “I felt like I could be friends with them,” she comments. “I never thought of them really as white guys. They were the Beatles!”

One racially significant episode, recounted in Eight Days a Week, goes beyond the question of musical imitation or fan reactions. During their second tour of the United States in the summer of 1964, the Beatles were scheduled to perform at the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Florida, then a segregated venue. The group was adamantly opposed to performing in segregated settings, though: at the time, Paul commented that segregation “just seems mad to me…You can’t treat other human beings like animals.”

Because of the Beatles’ stance, the Gator Bowl concert ultimately occurred but with an integrated audience. The historian Dr. Kitty Oliver, who grew up in the segregated American South, recalls attending the concert as a teenager. Being surrounded by white people made her apprehensive, but this feeling soon faded and Oliver found herself “yelling as loud as I could and singing along.”

Oliver comments, “That was the first experience I had where it was possible to be around people who were different, and at least for a while these differences could disappear.”

Danger: The jubilant fan enthusiasm for the Beatles had a more ominous flip side: the frenzy elicited by the band could easily turn to reckless behavior or even violence. Various moments in Eight Days a Week and Beatles ’64 make clear the danger underlying their celebrity.

Sometimes the potential danger associated with the Beatles is explicit. Eight Days a Week reveals that the mile-long queue of Beatles’ fans mentioned above led to the police and ambulances being called in and over 100 fans needing help, if only because they had been standing in the rain for so long.

We hear about or see footage of fans rushing the stage during Beatles’ performances, such as in Vancouver in 1964, the 1965 Shea Stadium concert, or a 1966 performance in Cleveland. Elsewhere we see photos of kids at Beatles concerts who ended up bleeding or on stretchers.

Confronted with rampaging fans, police officers clearly struggle to maintain order. Kane observes that “None of the police in any of the cities were prepared for this.”

Eight Days a Week also shows how John’s infamous 1966 comment about the Beatles being “bigger than Jesus” sparked a backlash that could have flared up into violence. Ed Freeman, a folk-musician-turned-Beatles-roadie, recalls a bomb scare when the band was touring Memphis.

Sometimes the danger is more implicit yet somehow all the more striking for that. Footage shot from within a car while the Beatles were riding in it shows fans running from the sidewalk into the road to touch the car or put their hands on the car windows. The musicians react with good humor to it all, but the images show just how close anyone off the street could get to them.

Perhaps the most unsettling incident in the two documentaries was recorded by the Maysles and is featured in Beatles ‘64: two teenage girls get into the Beatles’ hotel (“We came in the other way, through the drugstore”) and roam the halls looking for the group. Soon a police officer intercepts them and a brief, awkward conversation ensues, as the girls hem, haw, and lie to the officer. The officer finally escorts them out. The moment passes without comment but underlines just how vulnerable the band was.

These moments achieve added weight from two pieces of historical context. The first is how the Beatles’ first visit to America and subsequent careers unfolded in the aftermath of John F. Kennedy’s assassination (the Ed Sullivan show appearance was less than three months after the president’s death) and against the backdrop of the other assassinations and violence that marked the era.

Both documentaries note this context. Beatles ’64 opens with a recap, through archival footage, of Kennedy’s all-too-brief presidency before beginning the main story of the Beatles’ tour. Eight Days a Week contains references to the 1964 murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner and the 1966 mass shooting at the University of Texas.

The second piece of historical context, of course, which neither documentary overtly mentions but is inescapable, is the fact that John’s life would ultimately be ended and George’s life foreshortened by deranged attackers. In light of the material shown in Eight Days a Week and Beatles ’64, what is remarkable is not the tragedies that befell two members of the Beatles but how safe they stayed for so long.

Solidarity: Amid the dangers, the fan frenzy, and the media circus, the crucial factor that allowed the Beatles to function and to produce great music was the communal bond among the four men. The band was, as Paul affectionately puts it, “a four-headed monster.” They all depended on and trusted each other, at least in those early days, and both documentaries highlight that group solidarity.

This solidarity shows up in the Beatles’ easy camaraderie and clowning in moments of downtime. We see this, for example, in the Maysles’ footage of Paul and Ringo in their hotel room mock fighting for the filmmakers’ attention: “No! Me! Me!” they shout as they stick their faces in front of the camera.

Solidarity is also a key part of their live performances, for a very basic practical reason. As Ringo notes, the fans’ screaming combined with the primitive nature of the equipment made it impossible for them to hear each other. They had to do their best to stay in tune and maintain the proper tempo simply by visual cues.

Recalling the Shea Stadium concert, Ringo explains, “I could not hear anything. I’d be watchin’ John’s arse, Paul’s arse, his foot’s tappin’, his head’s noddin’, to see where we were in the song.” (I note that one shot from the performance footage in Eight Days a Week gave me a renewed appreciation of Ringo’s work: viewed from the side as he plays, it becomes apparent just how hard he is whaling on the drums. The sheer physical exertion involved is amazing.)

In Eight Days a Week, Paul discusses a quieter but no less important aspect of the group bond when he describes in loving terms his song-writing process with John:

“[W]e would be in a hotel room with two twin beds, and he’d have his acoustic guitar, I’d have mine, [we’d] sit opposite each other, and because I was left-handed, he was right-handed, it was like looking in a mirror. And we’d just start something and ricochet off each other. He’d do a line, I’d do a line. And we’d just write it down.”

At the end of a day, they would have paper with the lyrics on it and (not being able to read music) would remember the chords.

In a post-Beatles archival interview, George makes the perceptive comment that the band had the advantage of “being four together. You’re not like Elvis, you know? I always felt sorry for Elvis, ‘cos he was on his own. He had his guys with him, but there’s only one Elvis. Nobody else knew what he felt like. But for us, we all shared the experience.”

Given their common themes and their similar approach to the material, the main difference between Eight Days a Week and Beatles ’64 is scope: the three-plus years of the Beatles’ careers covered in Eight Days a Week versus the two weeks covered in Beatles ’64. Each approach has its advantages: breadth in Eight Days a Week versus focus in Beatles ’64.

Both documentaries are enjoyable, but I slightly preferred Beatles ’64. Keeping the narrative limited to the Beatles’ first US visit and its impact gives the documentary a tighter structure and a clear beginning and end. By tackling the whole of the Beatles’ early careers yet then ending well before the band’s break-up, Eight Days a Week feels a bit more shapeless, like an attempted biopic that abruptly cuts off in the middle.

Another subtle advantage of Beatles ’64 is that I found the commentary of the various interviewees in that movie slightly more interesting. In particular, Jack Douglas has an elaborate story about attempting to follow in the Beatles footsteps through a visit to Liverpool that is probably the most entertaining anecdote in either documentary.

The differences between the documentaries are relatively minor, though. What both offer are light, entertaining takes on the Beatles during the era when they were most popular, most united, and most fun.