The next entry in my Zhang Yimou retrospective poses the question: what happens when wuxia warriors face off against giant lizard monsters? Watch The Great Wall to find out!

Five years after making The Flowers of War, his first film with a major Hollywood star, Zhang Yimou directed The Great Wall (2016), which featured not only another big western star but a far more western production all around.

For the first time in his career, Zhang was working from material written by non-Chinese writers: The Great Wall screenplay was written by Carlo Bernard, Doug Miro, and Tony Gilroy, from a story by Max Brooks, Edward Zwick, and Marshall Herskovitz. The result is an action-adventure movie that blends wuxia with Hollywood blockbuster.

Set sometime in the 12th century, The Great Wall begins with an English mercenary, William (Matt Damon), and a Spanish mercenary, Tovar (a pre-Mandalorian Pedro Pascal) traveling through the Chinese wilderness in search of the land’s fabled “black powder,” that is, gunpowder. They hope to make their fortunes off the superweapon.

The mercenaries soon get more than they bargained for, though. First, they are attacked at night (and lose two traveling companies) to some mysterious beast that William wounds and that leaves behind a giant scaly claw. Next, when they reach the Great Wall of China, they are captured by Chinese forces.

The Chinese garrison at the Great Wall keep William and Tovar alive largely because they are intrigued by how William wounded the scaly attacker. The reasons why soon become clear.

China is under attack by creatures known as the Tao Tei, giant monsters that seem to be mixture of dinosaurs, the Xenomorphs from Aliens, and the Wargs from Lord of the Rings.

Hordes of Tao Tei repeatedly assault the Great Wall in attempts to break into China. The garrison, who are clearly old pros at dealing with this kind of threat, repel them not only with gunpowder but other weapons such as flaming projectiles launched by catapult and scythe-like blades embedded in the Wall.

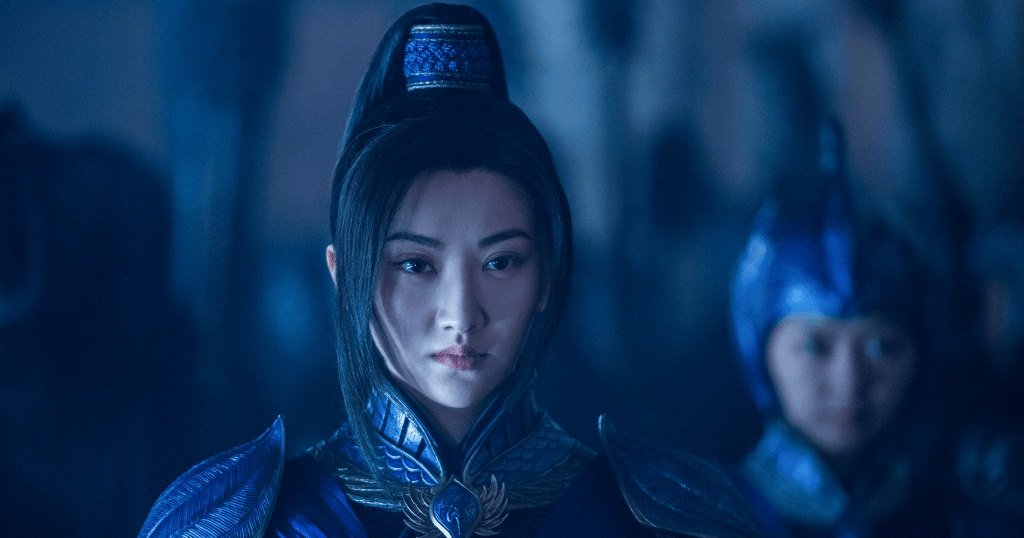

The Chinese also have a crack team of all-female soldiers who rappel down the Wall on ropes to engage the Tao Tei at close quarters. The leader of these soldiers, Commander Lin Mae (Jing Tian), detests the western mercenaries for being greedy and self-interested. As she tells William, Chinese warriors live by a different code, which prizes loyalty to country and trust among comrades-in-arms.

Also on hand is another westerner, Ballard (Willem Dafoe), who has been a prisoner at the Great Wall for many years (his presence both explains how Lin Mae knows English and allows him to provide exposition to the protagonists). Ballard has an agenda of his own and is soon trying to enlist William and Tovar in his schemes.

This situation soon presents William with a choice: will he continue with his self-interested ways or will he help the Chinese against the monstrous threat to their homeland?

At this point in the review, the reader should have a pretty good sense of what kind of movie The Great Wall is. That is, this is a dumb, ultra-cheesy, CGI-drenched action movie that is about as far from Raise the Red Lantern or Zhang’s other thoughtful dramas as you can get. Pretty much every step of the plot is predictable, characterization is minimal, and battles against big green monsters are plentiful.

Clearly a movie like this does not qualify as real cinema (I envisage Martin Scorsese frowning at it). And clearly if I want to be a Serious Movie Reviewer I should decry it.

Actually, though, I liked this movie. It’s dumb, but it’s also fun.

While the story may be predictable, the screenplay tells it with admirable efficiency. The Great Wall is fast paced, with each scene advancing the plot in some way. Characters and their motivations are established quickly. Plot points are carefully set up to be paid off later. Everything is neatly wrapped up in a brisk 93 minutes.

Zhang and his frequent cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding render the movie with all the brilliance we would expect from one of their collaborations. The Great Wall is largely free of what Steven Greydanus dubbed “Medieval Grunge.” Instead, colors pop off the screen.

We are treated to the yellow and rainbow hues of the Chinese deserts. The different types of soldiers at the Great Wall are distinguished by color-coded armor of blue, red, black, gold, and purple.

During an episode set in the capital city, we get an imperial court filled with vibrant yellow, red, and green.

A crucial scene late in the movie is set in a tower whose stained-glass windows cast kaleidoscopic light on the characters. Even the Great Wall, which must necessarily be gray stone, is colored what I can describe only as a vivid gray, the archetype of gray.

While the action sequences involve the computer-generated Tao Tei and thus are a poor substitute for live-action stunt work, Zhang and his team still find inventive ways of staging these sequences. To give just a few examples:

I appreciated how the Tao Tei herd together and use their fan-like armor to protect the queen of the species. I liked a scene where William must face a Tao Tei beast despite a thick fog preventing him from seeing it—and where Lin Mae provides a clever means of getting around this obstacle. I also liked the touch of Tovar employing matador techniques against one of the beasts.

Some running business involving a captured monster and a magnet pays off well in the heroes’ final plan to defeat the Tao Tei (the climax admittedly relies on an overly pat conceit straight out of the Phantom Menace, but the whole business was entertaining enough that I could forgive that).

Also, I must say that, digital or not, the toothy, usually blood-drenched maws of the Tao Tei are pretty frightening to behold. The movie definitely sells the threat posed by these creatures.

All the actors pitch their performances at the right level, committing to the story as if it were classic mythology. Matt Damon and Jing Tian play off well against each other, William’s taciturn stubbornness contrasting with Lin Mae’s fiery intensity. They effectively show how the pair’s relationship grows from hostility to wary trust to mutual respect with a hint of romantic attraction.

Meanwhile, Pedro Pascal, as the hero’s sidekick, gets to have fun as the more cynical, sarcastic side of their partnership. An exemplary moment is when, after William has amazed the Chinese soldiers with a display of his extraordinary archery skills, Tovar responds with a yawn.

Pascal and Damon have an easy-going chemistry and share some amusing banter. At one point Tovar, who has been increasingly exasperated by his friend’s behavior, intervenes to help William out of a life-threatening situation. Tovar comments, “I’m only doing this so I can kill you myself later.”

As Ballard, Willem Dafoe does not have much to do, but he gets at least a few entertaining opportunities to display the character’s basic amorality.

Let me clear: The Great Wall is no masterpiece and certainly nowhere near the best film Zhang has ever made. Yet if I had to sit down and watch a mindless action movie in which appealing actors exchange quips amid slugfests with CGI monsters, I would easily take The Great Wall over Jurassic World or most MCU movies.

A long-time cliché among movie buffs is that international cinema is the place to go for serious, avant-garde filmmaking that you cannot find in Hollywood. And now it seems that international filmmakers even do dumb, special effects-heavy action movies better than Hollywood. This is perhaps the unkindest cut of all.