Next in my Beatles retrospective, I turn to the dazzling Yellow Submarine.

When I was a kid, my introduction to the Beatles came from two sources. The first was my older sister, who was a massive Beatles fan in her teenage years. Beyond owning many of the albums, she plastered her room in our house with posters of the Fab Four and even hung up a humorous collage featuring the group’s sometime guru, the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. The first video we ever rented as a family, once home video became an option, was A Hard Day’s Night—I can only assume because of her advocacy. The Beatles were thus an inescapable presence in our household when I was growing up.

(My sister later moved on to other interests, but as a result she performed one of the greatest acts of generosity one human being can show to another: she handed down her Beatles albums to me!)

The second source of my youthful exposure to the Beatles was the movie Yellow Submarine (1968). As I recall, Channel 56 out of Boston would periodically show the movie as a Saturday matinee, and since it was a kid-friendly animated flick I would watch it.

The movie’s otherworldly setting and quest/adventure story made it feel like other fantasy adventures I ate up when young, a sort of hippie version of The Hobbit or the Chronicles of Narnia. Yellow Submarine was full of the sort of arcane details and terminology (Pepperland! The Sea of Monsters! The Dreadful Flying Glove!) that suggested a vast realm of world-building beyond the movie’s plot.

Overall, I think the impression Yellow Submarine left on my young self was that the Beatles were part of an elaborate realm of mythology with its own stories and associated lore that only older people more well-versed in it than I could fully grasp…all of which, as it happened, turned out to be true.

In retrospect, what is remarkable about this movie that helped provide my earliest view of the Beatles is how little the four musicians had to do with the project.

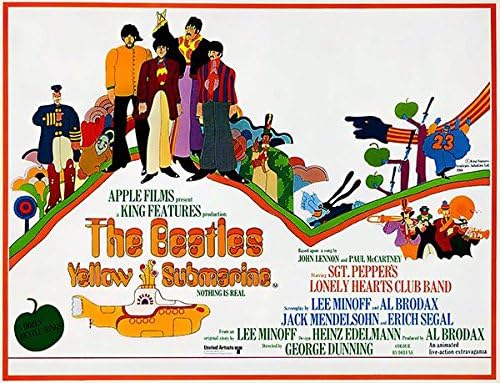

Directed by George Dunning and written by Lee Minoff, Al Brodax, Jack Mendelsohn, and Erich Segal, Yellow Submarine was an attempt to fulfill the group’s 1963 deal with United Artists for a three-picture deal without the Beatles actually having to go through the tedium of making another movie. An animated movie that featured the likenesses of John, Paul, George, and Ringo as well as copious Beatles songs seemed a way to square that particular circle. The notion even had a certain precedent, as Al Brodax had already created a comical TV series in the United States starring animated versions of the Beatles. Production accordingly went forward, with minimal input from the band.

Despite such an inauspicious origin, though, the venture paid off: Yellow Submarine turned out to be a fun, visually inventive movie with fantastic music.

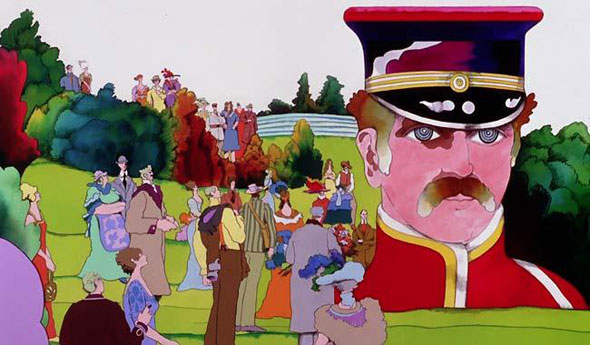

The movie opens in the green, idyllic country of Pepperland, which lies (or lays? I forget) deep beneath the sea and where peace, love, and music reign.

However, Pepperland is attacked and invaded by the wicked Blue Meanies, who hate happiness in general and music in particular. The Meanies freeze the people of Pepperland in a kind of suspended animation, turning the normally colorful society gray.

One man escapes the Blue Meanie invasion, though. The graybeard official known as Young Fred sails off in Pepperland’s treasured yellow submarine to find someone to help liberate the country.

Young Fred sails the submarine to Liverpool and quickly seizes upon Ringo Starr as the man who can help. Ringo is game and enlists the other Beatles to join in the quest.

A touch I appreciated here is how the movie does not waste time on exposition: whenever a situation requires Young Fred to explain his plight, he simply lets out a string of sub-verbal grunts and yells culminating in the cry “Blue Meanies!” The Beatles intuitively understand.

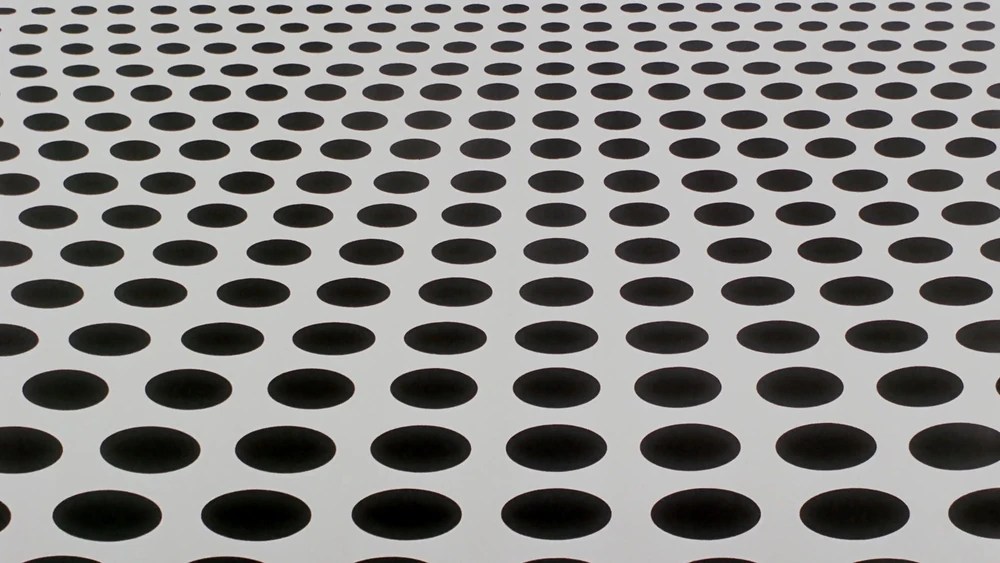

On their odyssey to Pepperland, the Beatles and Young Fred travel through various extraordinary places such as the Sea of Time, where time can run rapidly backwards or forwards; the Sea of Monsters, populated by strange, vaguely dinosaur-like creatures; the Foothills of the Headlands, populated by gigantic Easter Island-style heads; or the Sea of Holes, a panorama of holes in time and space that collectively form a vast optical illusion.

Along the way, they also meet Jeremy Hillary Boob, Ph.D, a fellow who is part koala, part commedia dell’arte mask, with a little bit of peacock thrown in. Jeremy speaks in rhyme and pretends to be much smarter than he is, but he can be loyal and useful in a tight situation.

Do the Beatles ultimately free Pepperland from the iron (gloved) fist of the Blue Meanies? Of course they do! Needless to say, though, the story does not really matter; the whole point is just to enjoy the array of stunning animated sights on display and listen to Beatles songs. The movie delivers beautifully in both respects.

Yellow Submarine is notable for how it borrows, steals, and mashes up so many different styles and types of imagery. Although most of the movie is hand-drawn animation, George Dunning and his animators also throw in some live action footage and in places use rotoscoping, a technique in which animation is drawn over live action film footage.

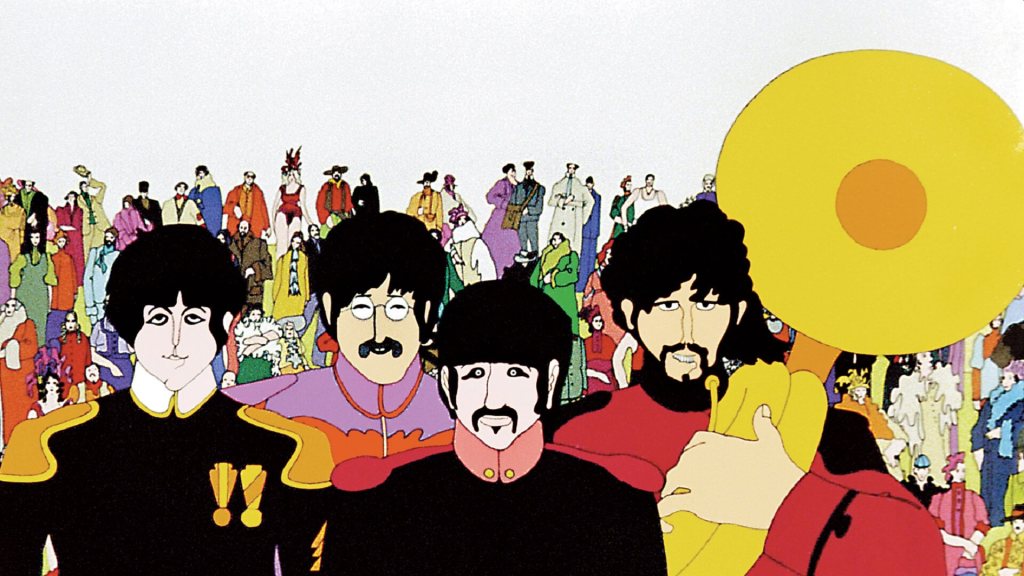

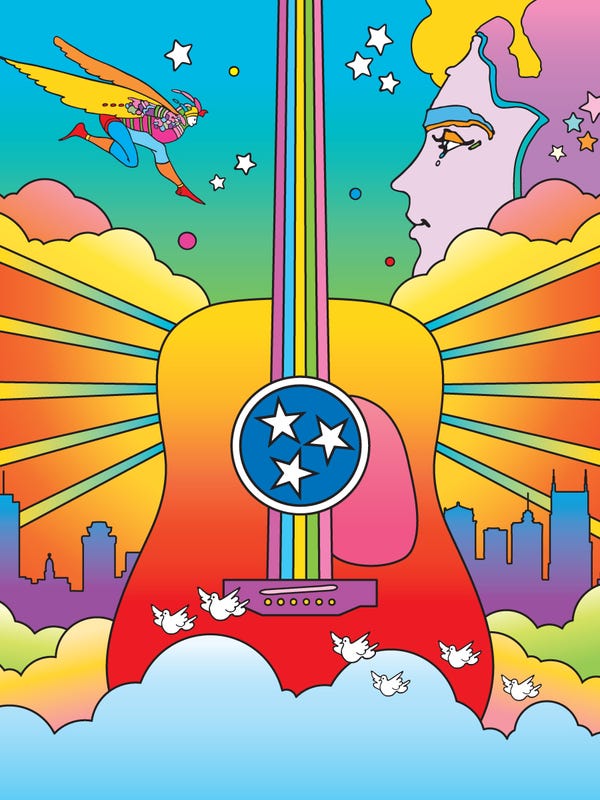

The dominant artistic influence seems to be the brilliantly colored psychedelic art of Peter Max.

Max was friends with the Beatles and says that John Lennon wanted him to oversee the movie’s artwork. He did not end up playing that role, but he recommended artist Heinz Edelmann, who became the movie’s art director. Under Edelmann’s supervision, much of Yellow Submarine feels like an homage to Max.

Other artistic influences or styles turn up as well. Some of the visuals are reminiscent of comic strips or editorial cartoons: Pepperland’s inhabitants, with their exaggerated proportions and vaguely Edwardian style, feel like they stepped out of a turn-of-the-century magazine. Some visuals are clearly influenced by pop art, as with the warehouse-like room Ringo and Young Fred tour that is filled with giant images of Marilyn Monroe, Buffalo Bill Cody, the Phantom, and the like. A sequence drawn to accompany “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” has a distinctively Toulouse Lautrec feel.

A dominant theme in the character design is surreal juxtapositions of elements, as with Jeremy’s mishmash anatomy or the Pepperland animal that appears to be a dog/monkey hybrid or the undersea monsters, such as the winged horse-centaur creature that coughs up random objects such as an ice cream cone or a gas pump.

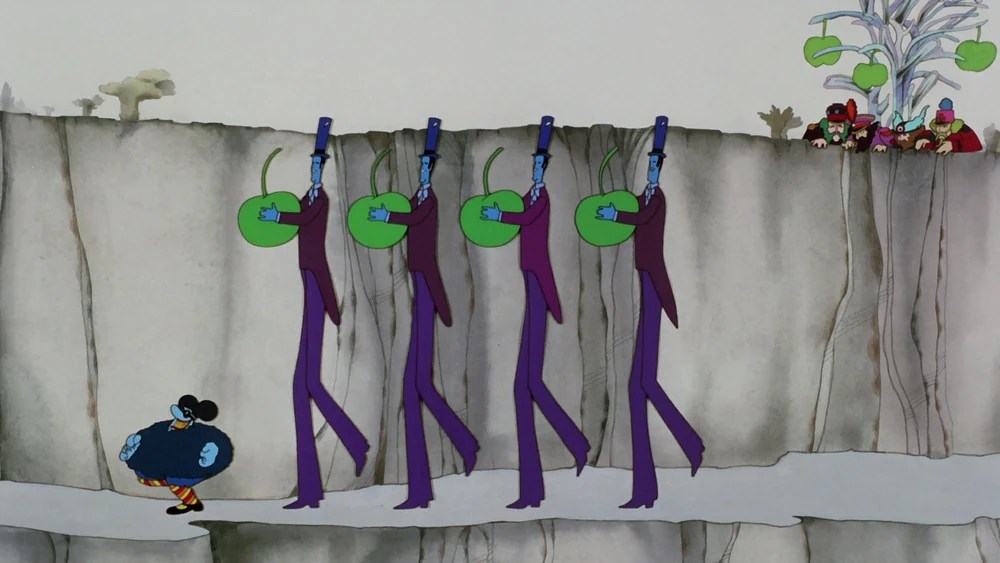

The animators also come up with fun character designs for the various fiendish creatures in the Blue Meanies army, such as the Apple Bonkers (men in suits and top hats with impossibly long stilt-like legs who drop green apples on their prey) or the Flying Glove, a giant, anthropomorphic blue glove that punches and squashes all in its path.

Overall, the art in Yellow Submarine is immensely creative and casts a long shadow over subsequent animated features. Former Pixar honcho John Lasseter once commented that the movie “pave[d] the way for the fantastically diverse world of animation that we all enjoy today.”

While I cannot confirm direct influences, I see shades of Yellow Submarine’s style in the movies of Ralph Bakshi, Gisaburô Sugii’s Night on the Galactic Railroad, and Benoit Chieux’s Sirocco and the Kingdom of the Winds. Even some Hayao Miyazaki’s movies, such as Spirited Away or The Boy and the Heron, while quite different stylistically, have a Yellow Submarine vibe, with their arrays of grotesque characters and settings (although I am sure Miyazaki would never, ever admit to such an influence).

To accompany the movie’s visual delights, the writers have come up with appropriate banter for the Beatles and other characters to toss back and forth. Some of the droll exchanges are Alun Owen-worthy. When Young Fred is initially pleading for Ringo’s assistance, they have this exchange:

YOUNG FRED: Help! Help! Help!

RINGO: Thanks, we don’t need any.

YOUNG FRED: Help! Won’t you please, please help me?

RINGO: Be specific.

When the submarine is traveling through the Sea of Time, the Beatles discuss the situation’s implications:

GEORGE: Maybe time’s gone on strike.

RINGO: What for?

GEORGE: Shorter hours.

RINGO: I don’t blame it. Must be very tiring being time, mustn’t it?

GEORGE, JOHN, PAUL: Why?

RINGO: Well, it’s a twenty-four-hour day, isn’t it?

Later, they comment on some of the creatures in the Sea of Monsters:

GEORGE: Hey! There’s a Cyclops!

PAUL: Can’t be. It’s got two eyes.

JOHN: Must be a “bicycle-ops” then.

RINGO: There’s another one.

JOHN: A whole “‘cyclopedia”!

These exchanges, and all other Beatle dialogue in the movie, are delivered not by the musicians themselves but by voice actors. For the most part, they do a good job. To be precise, Paul Angelis does a very good imitation of Ringo and fairly good imitation of George, while Geoff Hughes does a fairly good Paul. John Clive, however, sadly does not sound that much like the real John.

Lance Percival, who does Young Fred, and the other voice actors also do fine work, although I pity the poor sods in 1968 who had to decipher a lot of the nonsensical, heavily accented dialogue. When re-watching the movie, I relied on subtitles.

The most important part of the soundtrack, though, is not the dialogue but the music. This comes through crystal clear and, since the filmmakers could draw on the Beatles’ later work, Yellow Submarine probably has the best soundtrack of any Beatles movie up to that point.

We get to hear songs from classic albums such as Rubber Soul (“Nowhere Man”), Revolver (“Eleanor Rigby” and the title track), and Sgt. Pepper (“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” “When I’m Sixty-Four”), as well as the single “All You Need is Love.”

The Beatles also contributed four previously unreleased songs for this movie. Two were Lennon and McCartney compositions: “Hey Bulldog,” which boasts an energetic, driving electric guitar riff; and the catchy sing-along tune “Altogether Now.” Two were excellent George Harrison songs: “Only a Northern Song” and “It’s All Too Much.”

“Only a Northern Song” is George’s funny, characteristically tart comment on his frustrations about life within the band (“Northern Songs” was the name of the Beatles’ music publishing company). As Rob Sheffield commented in his book Dreaming the Beatles, the song’s essential message was “Help, I’m being held prisoner in a rock group.”

In contrast, “It’s All Too Much,” is a soaring, cacophonous yet triumphant anthem. While the lyrics are ambiguous—are the sentiments happy or sad? Is the theme romantic or spiritual?—the overall sound and feel is unmistakably joyful. The number accompanies the movie’s climax and is an appropriate note to end on.

Well, almost to end on: despite their lack of interest in doing another movie, the Beatles were so pleased with Yellow Submarine when they saw it that they agreed to appear as themselves in a brief live-action coda. There is not much to the coda: the four Beatles exchange some banter and then sing us out with a reprise of “Altogether Now.” They all appear so happy and relaxed, though (watch Paul trying not to crack up), that it makes for a smile-inducing conclusion to the movie.

Yellow Submarine is a great, visually and musically entertaining movie. Perhaps the only people who were not pleased by it, though, were the folks at United Artists, who apparently did not view it as genuinely fulfilling the three-picture deal. The Beatles would still have to make at least one more movie. Heading into 1969 and an increasingly fractious time in their lives, that is what the band would set out to do.