Continuing my Zhang Yimou retrospective, I consider the bittersweet Under the Hawthorn Tree.

Like many other artists, Zhang Yimou has certain scenarios and themes he returns to again and again. He also likes reworking essentially the same story in different variants, sometimes improving on the previous version: as I mentioned before, his early movie Ju Dou was essentially a more polished and confident version of his first feature, Red Sorghum.

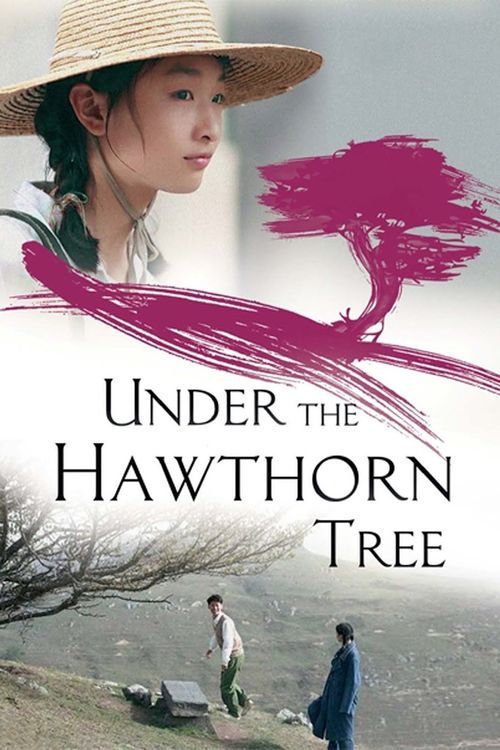

Zhang has performed a similar task with his movie Under the Hawthorn Tree (2010), written by Yin Lichuan, Gu Xiaobai, and A Mei, from a novel by Ai Mi. The movie felt to me like a more successful rendition of a lesser Zhang movie, The Road Home. Both are period pieces, seen from a young woman’s perspective, about romantic fidelity under the shadow of future tragedy. Under the Hawthorn Tree also allows Zhang to explore perhaps his favorite theme, perseverance, often of a quixotic kind.

Under the Hawthorn Tree is set in the late 1960s, during the Cultural Revolution. At the time, urban students were sent to rural areas to assist farmers and learn the value of manual labor.

Teenage Jing (Zhou Dongyou) is one such student. She goes to stay with a farm family in a village where a hawthorn tree with red blossoms grows. According to village lore, the blossoms are red rather than the usual white because the tree was watered by the blood of Chinese resistance fighters during the war with the Japanese.

While laboring on the farm, Jing meets Sun (Shawn Dou), an older student working as part of a geological exploration project in the village. The two take an instant liking to each other and a tentative romance begins between them.

Complications abound in their relationship, though: Jing has to return home once her stint in the village is over, both have to figure out their future careers, and Jing has to reckon with her mother (Xi Meijuan). Taxed with raising Jing and her two younger siblings on her own, the mother does not like the idea of Jing being in a relationship at such a young age.

For a while, Jing and Sun try to sustain a furtive long-distance relationship while Jing pursues a stable position as a school-teacher. Sun provides little gifts, sometimes to assist Jing and her family in their poverty, sometimes just to show his affection. As time goes on, Jing and Sun begin to take bigger risks of various kinds in their romance. Then, fate intervenes in an unexpected way.

For roughly its first half, Under the Hawthorn Tree tells a sweet, absorbing love story. Tales of prohibited or discouraged romance are reliable sources of two kinds of dramatic tension: the tension over if and when the couple will express their feelings and the tension of whether they will be found out and punished.

Under the Hawthorn Tree effectively generates both varieties of drama. The movie is especially good at evoking the romantic power that outwardly tiny expressions of affection can have. I appreciated a quiet, romantic scene where Jing and Sun oh-so-slowly but surely hold hands. (Take that, Mr. Darcy Hand Flex!)

In many ways, the general contours of the love story will be recognizable to people from across a variety of nations and cultures. Jing and Sun are like so many adolescents in love: swept up in the excitement of their relationship and frequently not thinking clearly or prudently about their future plans.

The movie also does not shy away from the darker aspects of romantic fixation. At one point, Jing is injured while working but is unwilling to go to hospital, not liking hospitals or doctors generally. Sun responds by cutting his own arm so he will need to go the hospital and thus Jing will too.

When Jing talks to her mother about her love for Sun, the mother offers a caution offered by innumerable mothers around the world: Sun may profess eternal devotion, but such professions are easier to utter than to prove in action. I also liked the grins and pokes Jing’s brother and sister direct at her during this scene, in the universal sibling language of “You’re in so much trouble now!”

Alongside these broadly recognizable circumstances, though, are characteristics distinctive to the story’s specific time and place. Jing and Sun must navigate not merely parental or social pressures but political ones.

The young couple’s future livelihoods depend on the approval of Party officials, and inappropriate behavior on Jing’s part could jeopardize her teaching position. Moreover, Jing’s family already lives under a cloud: the mother is raising the family on her own because her husband is in prison for being a “rightist.” Sun must deal with a similar situation, as he makes clear by relating a horrifying story about his own mother.

The screenplay memorably captures the characters’ political world through various verbal tics in how people express themselves. Personal decisions or plans are repeatedly justified or explained with references to the good of the Revolution or the guidance of Chairman Mao. Characters will sometimes express vague hopes for the future by invoking the phrase “if policies change,” which has a similar quality here as “Lord willing” might have in another society.

The nature of life during the Cultural Revolution is also made clear visually in a brief sequence where Jing and her classmates rehearse a song-and-dance routine celebrating Communism. The camera neutrally records the sequence in a few long shots, and the students come across as just another typical group of teenagers doing a school activity—they could be high schoolers anywhere practicing for the school musical. The lyrics they sing convey a different impression, though.

Meanwhile, this being a Zhang Yimou movie, a Tragic Reversal is likely and does indeed occur before the movie’s end. The reversal places Jing and Sun’s relationship and the meaning of mutual devotion in a whole new context. The later passages of the movie also include a subplot about one of Jing’s classmates and her parallel romance, whose deeply sad and painful conclusion offers a counterpoint to the Jing and Sun relationship.

This kind of small-scale character drama depends immensely on the performances, and Under the Hawthorn Tree succeeds here. Xi Meijuan plays Jing’s mother with a muted concern that still conveys deep worry, sadness, and love. Shawn Dou, as Sun, comes across as friendly but somewhat hard to read, which keeps us guessing about his character. When the movie calls for more demonstrative acting, though, Dou rises to the challenge.

The heart of Under the Hawthorn Tree, however, is Zhou Dongyou’s performance as Jing. The waif-like Zhou, who was 18 at the time of the movie’s production and looks several years younger, proves more than equal to the task of carrying a movie. She can express an array of emotions just through her face, particularly her eyes, and makes clear the personal odyssey Jing goes through over the course of the story.

Two scenes stand out as highlights of Zhou’s abilities. During a meeting with Sun when it seems like he might kiss her, a wonderful mixture of anxiety and excitement ripples across her face. Later, in a tricky scene where Jing and Sun are confronted with a crucial decision, Zhou brings an almost excruciating intensity to the moment.

The movie does not have flashy visuals, but cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding does render the Chinese countryside in profound shades of green that are beautiful. Zhang’s knack for composition remains sublime, and together he and Zhao provide endless suitable-for-framing shots.

The final passages of Under the Hawthorn Tree depart from the relative realism of the rest of the movie and take a turn into outright tear-jerking melodrama. I daresay this shift will turn off many viewers. However, I did not mind.

I liked the end of the movie partly because it seemed so clearly to invite a symbolic or allegorical interpretation that strict realism was not necessary. In particular, the screenwriters’ choice to be deliberately vague about a key plot point suggests that the precise details of the conclusion are less important than what the conclusion implies about the Cultural Revolution and its consequences.

Also, I liked the end of the movie partly just because I found it very affecting. Maybe Under the Hawthorn Tree did not “deserve” such a reaction, but whether and why a particular work of art elicits emotion is mysterious. I think by the end of the movie I had come to care enough about the characters and their experiences that I was willing to accept the implausible conclusion and even be moved by it.

The final emotional cut comes from some ending title cards that provide both an epilogue and a few lines of verse. The verse offers an understanding of “devotion” that is unbearable in its poignancy.

Leave a comment