I kick off my Beatles retrospective by looking at the movie that started it all, A Hard’s Day Night.

Expressions such as “one of a kind,” “sui generis,” and “lightning in a bottle” exist to describe A Hard Day’s Night (1964).

Directed by Richard Lester and written by Alun Owen, the movie is pure, concentrated cinematic joy: fun and funny, with a relaxed attitude toward its subjects, the Beatles, that makes the whole endeavor immensely likeable.

A smash hit when it was released, the movie remains well-regarded to this day, receiving near-uniform praise from the 100+ critics aggregated by Rotten Tomatoes (Jonas Mekas of the Village Voice was a rare dissenter). Roger Ebert included it in his pantheon of “Great Movies,” calling it “one of the great life-affirming landmarks of the movies.”

Even the notoriously acerbic Dwight Macdonald, who turned a baleful eye on works by Ingmar Bergman and Akira Kurosawa and dismissed 2001: A Space Odyssey as an “over-long and over-blown space fantasy,” was charmed by A Hard Day’s Night. Macdonald pronounced the movie “not only a gay, spontaneous, inventive comedy but…also as good cinema as I have seen for a long time.”

A Hard Day’s Night’s success is all the more striking given how unpromising it seemed on paper. The movie was a vehicle for a group of non-actor musicians, which was not a genre that had a good record of producing quality movies, either before (see the unhappy history of Elvis Presley’s movie career) or since (see, say, Cool as Ice or Spice World). It was intended to be a quick, easy attempt to make some money off a pop group, at least in part through the music publishing rights and tie-in soundtrack albums.

Richard Lester, although he had an Oscar-nominated short film on his resume, was not a top-tier director at the time. The expatriate American living in Britain had mainly done TV and a few features prior to working with the Beatles. His budget for the movie was so low that he had to shoot in cheap black and white, over a rushed film shoot of about seven weeks.

And yet…

Part of the movie’s success was simply the result of perhaps the best timing in film history. United Artists, the studio responsible for A Hard Day’s Night, signed the Beatles to a three-picture deal in late 1963, when they were popular in England but had not yet become mega-stars. The resulting film came out in the summer of 1964, after the group’s American tour and appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show, when Beatlemania was at its absolute fever pitch. A commercial hit was almost guaranteed under these circumstances.

Still, benefiting from the Beatles’ insane popularity in 1964 cannot explain A Hard Day’s Night’s positive critical reception or its enduring appeal. So, what is so memorable about the actual movie?

The plot is easy enough to summarize. Over the course of perhaps two or three days, the Beatles travel by train to London, to perform a televised concert. Accompanying John, Paul, George, and Ringo are the short, irascible Norm (Norman Rossington), who serves as a fictional stand-in for Beatles manager Brian Epstein, and the lanky, gormless Shake (John Junkin), who I suppose stands in for the road managers Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall.

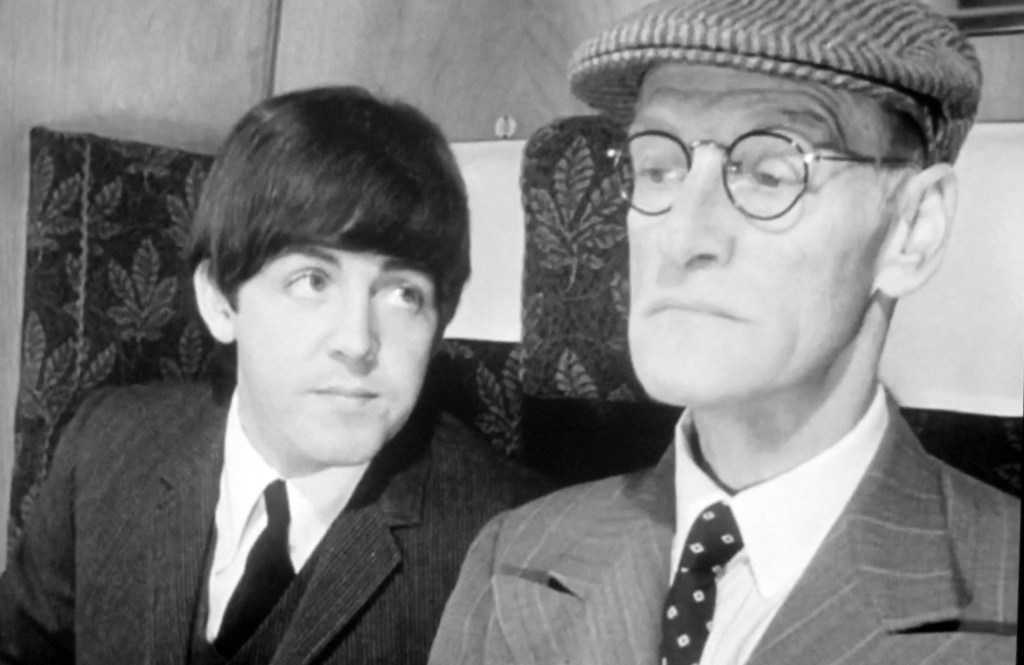

Also along for the ride is John McCartney (Wilfrid Brambell), a (very) fictionalized version of Paul’s grandfather. Although we are repeatedly assured that the elder McCartney is “a clean old man,” he is actually a mean-spirited, lecherous schemer who loves to cause trouble.

As they rehearse for the upcoming concert, the Beatles joke around with each other, flirt with attractive women, poke fun at various pompous authority figures, and try to get a moment’s peace amid the pressures of being on tour. Something approximating dramatic conflict emerges in the movie’s latter half as Ringo wanders off on the eve of the concert (the result of Grandfather McCartney’s machinations) and the other three must scramble to get him back in time.

In the end, though [spoiler alert?] Ringo returns in time for the concert and the Fab Four perform a rocking set for their adoring fans.

The movie’s minimal plotting is among the many strengths of Alun Owen’s screenplay. We can all be glad Owen did not write a more conventional story involving high stakes, villains, or romantic sub-plots. Such a story-line would have felt corny and not been a good fit for the four stars.

Instead, the movie gives us what fans, in 1964 and now, really want: plenty of opportunities just to hang out with the Beatles while they play music and act charming. Owen and Lester, combined with cinematographer Gilbert Taylor and editor John Jympson, inventively use all their resources here to back up the Beatles with a rapid-fire array of gags and comical bits.

The comedic moments include sitcom-style mix-ups, as when Grandfather McCartney pretends to be a wealthy high-roller to gain entrance to a posh casino or George is mistaken for an aspiring actor. They include visual gags with props, as when a TV actor playing a wounded soldier takes his lunch break, adds some ketchup to his chips, and, for good measure, thoughtfully adds some to his made-up wounds as well. They include visual gags with staging, as in a prolonged chase involving police officers and a would-be car thief. (This chase, filmed mostly in long shot, resembles silent comedy.)

The screenplay gives us plentiful verbal comedy, as with the nonsensical responses the Beatles give to reporters (“How did you find America?” “Turn left at Greenland”; “What do you call that haircut?” “Arthur”) or an odd little ballet of miscommunication John gets into with a female fan.

Sometimes Owen, who before writing his script spent time with the Beatles to get a sense of them, gets a laugh just from how he writes a line to fit their distinctive Liverpudlian cadences. Consider a moment when George cautions Paul on how to approach some schoolgirl admirers:

PAUL: Should I?

GEORGE: Aye, but don’t rush. None of your five-bar gate jumps and over sort of stuff.

PAUL: What’s that supposed to mean?

GEORGE: I don’t know, I just thought it sounded distinguished-like.

Or this brief exchange between George and Ringo:

GEORGE: Ah, you’ve got an inferiority complex, you have.

RINGO: Yeah, I know, that’s why I play the drums–it’s me active compensatory factor.

Lester and his team also get comedy from editing or camera movement. Consider the sequence at a reception where the camera weaves through the crowd to show how the Beatles are systematically kept from getting the sandwiches and beer they are vainly seeking.

In probably the film’s most famous sequence, where the Beatles cavort around a field to the strains of “Can’t Buy Me Love,” the filmmakers speed up the film to augment the frenetic quality of their antics. (Gilbert Taylor later revealed that the effect was actually the unintended result of a malfunctioning camera; a happy accident if ever there were one.) The sequence’s juxtaposition of four shots of each Beatle leaping through the air, with differing results, is especially funny.

Occasionally the movie breaks reality altogether for an outright surreal gag. The most memorable of these is when the Beatles suddenly appear outside a train (with George and Ringo riding bicycles) that moments before they were riding aboard. I also appreciated a moment when John suddenly appears at the end of a line of people he had previously been leading—a gag either I had not noticed before or I had forgotten but which made me laugh out loud on re-watch.

As far as the acting, the four Beatles do well in their first foray into movies. They all wisely do not try too hard, playing everything pretty low-key and coming across as bemused and relaxed. The screenplay gives them roughly distinguished on-screen personalities—John is a mischievous wise-cracker, Paul is earnest but turns on the charm for the ladies, George is dryly skeptical, Ringo is forlorn and somewhat naïve—that (for better or for worse) would define their public images for years.

John Lennon does particularly well, being funny in an unforced way. Some of his moments feel improvised, as when he provides a visual double entendre by mock snorting a bottle of Coca-Cola. A similarly impromptu impression of the Queen is probably the funniest moment in the movie.

Meanwhile, the supporting cast of British character actors must walk a tightrope. As the professionals in the cast, they need to provide an energy and polish that the musician stars cannot be expected to furnish, yet they also need to be worthy foils who allow our stars to show off their own cool. In effect, the supporting actors must be the comic relief and the straight men simultaneously. They pull off the tricky task with aplomb.

Wilfrid Brambell, as the Grandfather, hams it up in appropriate musical hall fashion. His comic timing is impeccable, and his not-so-clean old man performance contrasts well with his young, laid-back co-stars. Bramble injects some refreshing astringency into the mix.

Other actors do not go as far over the top as Brambell but give fairly broad performances as various characters the Beatles can have fun deflating. Stand outs are Richard Vernon as a stuffy businessman on a train, Kenneth Haigh as a pretentious advertising executive, and Victor Spinetti as the neurotically uptight director of the Beatles’ TV concert. Spinetti’s air of pained self-pity is especially amusing.

Above all, there is the music. A Hard Day’s Night includes 11 Beatles songs in total. In addition to “Can’t Buy Me Love,” these include “I Should Have Known Better,” “Tell My Why,” and “She Loves You,” all certified toe-tappers, with “I Should Have Known Better” boasting that wonderful harmonica work. We get a couple lovely ballads, “If I Fell” and “And I Love Her.” Most important, we get the title song, with its epic opening chord that also opens the movie.

Lester, Taylor, and Jympson apply the same inventiveness they brought to the movie’s comedy to filming the musical numbers. Sometimes, as with “A Hard Day’s Night” or “Can’t Buy Me Love,” the songs are simply played on the soundtrack over sequences of the Beatles and other characters running or goofing around. “I Should Have Known Better” is handled in a self-consciously artificial way, with footage of the Beatles initially playing cards on the train shifting into footage of them playing instruments and performing the song in the same setting.

Most of the songs, though, are presented just by showing the Beatles performing them on stage in the TV studio, either in rehearsal or in the final concert. Lester and Jympson assemble the footage of these performances into effective, visually varied sequences.

During the studio performances, the movie cuts from long shots of the band to close-ups of the band members’ faces or other details (Ringo’s hand tapping the drums, for example), from the performances as seen on stage to the performances glimpsed on monitors in the control room, from the Beatles to their fans in the audience, and so on. Some individual images in these sequences are striking, such as a magnificent shot of Paul in backlit close-up as he sings “And I Love Her.”

The use of fan footage during the concert is very well done. Although we sometimes hear that recognizable, hysterical “fan scream,” for the most part the filmmakers keep the fan noises faint or remove them altogether. The contrast between the Beatles performing their music while an audience of mainly teenage girls jump about and wave their arms in a kind of wordless ecstasy is somehow more powerful than if we could hear the audience.

As with the footage of the band, the filmmakers pick out memorable individual images of fans in the audience, such as a young blond woman who seems anguished with longing or a boy who is covering his ears to block out the screaming around him but is simultaneously adding to the noise by screaming at the top of his lungs. I also appreciated the filmmakers’ choice to start the concert sequence with a quick series of shots of four girls in the audience, each respectively mouthing “Paul!” “John!” “George!” and “Ringo!”

Viewed as a whole, A Hard Day’s Night is a quintessential example of art thriving on its limitations. Given limited money and limited production time, Lester and his team managed to strike cinematic gold, thanks to a mixture of their stars’ music and charisma, their own creativity, and an overall light touch.

If I had to offer any criticism of A Hard Day’s Night, it would be that, 60 years after its release, it does sometimes seem a bit slow. This is perhaps partly because of the movie’s self-consciously dead-pan style, but also partly because in the decades since its release we all have gotten so used to a breakneck pace for movies, especially when it comes to musical performances.

In this respect, A Hard Day’s Night could be considered a victim of its own success. Because of his work with the Beatles, Richard Lester was once famously called the “father of MTV”—and responded by demanding a paternity test. Such protestations notwithstanding, though, I think the family resemblance is clear.

Lester did indeed help to create the MTV-ified world of entertainment we now inhabit. Unlike the work of so many of his progeny, though, Lester’s work in A Hard Day’s Night has stood the test of time.

Leave a comment