The next installment in my Zhang Yimou retrospective also involves looking back at the inaugural work of the Coen brothers.

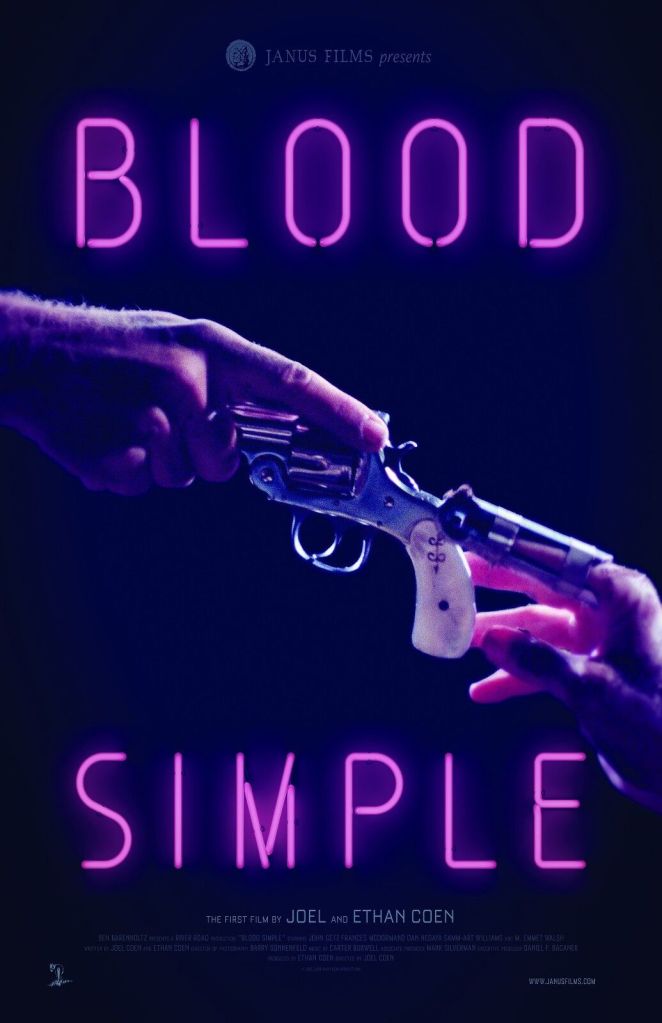

For his sixteenth feature, Zhang Yimou did something new: remaking another movie. Zhang’s movie A Woman, a Gun, and a Noodle Shop (2009) is a transplant to a Chinese milieu of Blood Simple (1984), the first movie made by Joel and Ethan Coen. Watching both movies and seeing how they compare therefore seemed the appropriate course of action.

Blood Simple takes place in rural Texas, amid a seedy world of dive bars, dingy houses and apartments, and lonely back roads. The story also takes place amid some of the seedier aspects of human life: adultery, domestic violence, greed, and murder.

Abby (Frances McDormand) is unhappily married to Julian Marty (Dan Hedaya), a sleazy bully of a bar owner. One night she begins an affair with Ray (John Getz), a bartender who works for Marty.

When private investigator Visser (M. Emmet Walsh) informs Marty of Abby’s affair, Marty pursues progressively nastier and more violent means of getting back at his wife. Eventually he makes a fateful decision: he asks Visser to kill Abby and Ray. After some slight hesitation, Visser agrees. This deal sets in motion a chain of sinister and violent events that do not go as anyone involved planned.

Blood Simple has an absorbing plot, with some good twists, but that plot is not the main draw here. This is a movie that depends more on atmosphere and detail than anything else.

Director Joel Coen and cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld make some striking stylistic decisions to create the appropriate effect. Appropriately for such a dark story, much of the movie takes place at night, with characters often shrouded in shadow.

Moreover, the movie is sparing in its use of establishing shots and long shots in general, emphasizing two-shots of characters (sometimes in confined spaces such as car interiors) and tight close-ups of faces.

We also get a lot of tight close-ups of other things: a pair of walking feet, a cigarette lighter, a discarded knife, a quartet of dead fish, a handgun.

This approach, which for all I know might have been dictated partly for budgetary reasons (if you do not have the most impressive locations, then you avoid showing them too clearly), works well on a storytelling level. The movie has a claustrophobic quality as it seems to take place in cramped spaces, and our limited sense of the characters’ surroundings is unsettling—what is happening just outside our field of vision? The big close-ups add a certain off-kilter quality, as if objects are out of proportion.

I should add that on the relatively rare occasions we do get long shots of an interior or a landscape, these shots have an eerie, lonely beauty to them. Two stand outs are a shot of a character silhouetted against the night sky and a shot of a farmer’s field in the early morning hours.

The atmosphere is aided by the screenplay written by both Coens. In contrast to their later work, Blood Simple is almost totally devoid of humor, instead taking a resolutely grim tone. The dialogue is sparse and artfully conveys how these not-very-articulate people try to communicate, as they often talk around issues and misunderstand each other. Several dialogue scenes play out slowly and awkwardly, with the sinister significance of what the characters are discussing heightening the tension and overall sense of unease.

The movie is also careful in how it uses violence. Until the final scenes, violent incidents are kept to a minimum. Yet blood plays a major role in the story: what little violence occurs produces plenty of it, and the Coens rely on the power of that to produce the necessary sense of horror.

Blood Simple’s central set-piece, and by far the movie’s most powerful sequence, follows Ray being presented with a macabre problem straight out of Hitchcock that unfolds in a nightmarish fashion. Two details in particular, one involving a truck traveling down a highway and another involving a decision that is not precisely violent but involves lethal consequences, are both masterfully chilling.

The cast serves the story well. John Getz, Frances McDormand, and Dan Hedaya all give moderately stylized performances. They are playing types—the Stoic Everyman, the Ditsy Wife, the Brutish Husband—rather than people and therefore avoid strict naturalism while not going too far over the top.

M. Emmet Walsh, however, gleefully hams it up as Visser, dispensing folksy pseudo-wisdom and laughing at his own unfunny jokes while engaging in villainy. Even Walsh makes room for some subtlety in his performance, though: I liked a couple silent moments when he allows Visser to look apprehensive, as if the private investigator is not quite sure he wants to commit the acts he has planned to carry out.

Blood Simple goes slightly astray in its final scenes, which resolve the story through a series of violent confrontations. These scenes are suspenseful and well staged, with particularly good uses of light and shadow. Nevertheless, they are a bit too conventional an ending for a movie that relies so effectively on a general mood of dread and the sense that everyone is guilty in some way. Can a shoot-out really resolve the evil that lurks in the human heart?

This minor misstep aside, Blood Simple is a very powerful latter-day film noir. Its power helps to explain why 25 years later Zhang Yimou opted to remake it.

The screenplay for A Woman, a Gun, and a Noodle Shop, written by Xu Zhengchao and Shi Jianquan, follows the original movie’s plot pretty much beat for beat. We get the same adulterous love triangle that leads to the same violent, complicated situations. The remake’s main points of interest, then, are how the story is localized in China, how Zhang opts to handle this material stylistically, and how the writers selectively depart from the original.

The movie takes place in what I take to be China’s far western Xinjiang region and is set sometime in the distant past, long before automobiles or telephones. The bar of the original has been replaced by the titular noodle shop owned by the wizened Wang (Ni Dahong).

Wang is a cruel miser who abuses his much younger wife (Yan Ni), who is having an affair with noodle shop employee Li (Xiao Shenyang). The private investigator role is filled by Zhang (Sun Honglei), a member of the local police force who is willing to earn money on the side by dishonorable means.

Also present are two characters without precise parallels in the original, noodle shop employees Zhao (Cheng Ye) and Chen (Mao Mao), both comic innocents out of their depth amid the bloody intrigues around them.

For some passages of the movie, director Zhang and cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding create a similar noir-style atmosphere to the original. Plenty of scenes are set at night, and the filmmakers make good use of the beautiful yet vast and desolate landscapes of their desert setting.

Presumably operating under fewer budgetary restraints than the Coens in their first feature, Zhang and Zhao fill the movie with long shots of the countryside or Wang’s large noodle shop-house complex that have a similar haunting emptiness to comparable images in Blood Simple. Time-lapse photography of clouds scudding across the sky, a recurring motif in the movie, add to the sense of foreboding: events constantly seem to be speeding to some dire conclusion.

Other visual touches work well. I liked how Zhang and Zhao give us overhead shots of the noodle shop that show how different characters are simultaneously pursuing different underhanded activities. At times, the filmmakers effectively use hand-held cameras to convey characters’ frenetic, panicked state of mind. Like in Blood Simple, stark contrasts of light and darkness are also employed memorably.

In a departure from Blood Simple, though, Zhang also injects elements of broad comedy and self-conscious absurdity into the story. Consistent with Zhang’s usual penchant for strong colors, Zhang and costume designer Huang Qiuping dress their characters in ways that opera stars might find a bit too flamboyant. Zhao, with his partly shaved head and top-knot, and Chen, with her pigtails and bangs, look like child characters from a pantomime.

Most of the cast give very big, histrionic performances. (The exception, in a kind of mirror image reversal of Blood Simple, is Sun Honglei, who is quietly scary as the corrupt police officer.) Characters do pratfalls or engage in various bits of slapstick. Along with the Coens’ influence, A Woman, A Gun, and a Noodle Shop also has a whiff of the bonkers’ comedy style of Stephen Chow.

Stylistic differences aside, the movie’s most notable change from Blood Simple is in its characterizations of Li and Wang’s wife. Unlike the Marlboro Man-like Ray, Li is written and portrayed as a bumbling coward who earns contempt for his weakness from his lover. Meanwhile, the fiery wife (who is never named) comes closer to a classic femme fatale than the naïve Abby.

Li is not only much weaker than Ray but also much more innocent. A Woman, A Gun, and a Noodle Shop has the same central set-piece as Blood Simple but with some crucial details changed. These changes make Li far less morally compromised than Ray and make the scene as a whole not so much chilling as just pitiable. That said, I appreciated how the business with the approaching truck on the highway is changed to the low-tech alternative of an approaching group of men on horseback.

The various changes made by Zhang and screenwriters and Xu and Shi are interesting, but overall I do not think they really work. The violent thriller elements and goofy comedy do not gel but instead produce a tonally disjointed quality to the movie.

Moreover, by absolving Li of the guilt that attached to Ray, the filmmakers take away the everyone-is-a-crook pessimism that was so crucial to the original movie’s sensibility. To be fair, I should acknowledge that the climax works better here than in the original for precisely this reason. A Woman, a Gun, and a Noodle Shop’s suspenseful showdown between sympathetic and unsympathetic characters is more consistent with the less morally gray events that preceded it.

I give Zhang and his team credit for trying something so different from his previous movies, but I would judge A Woman, A Gun, and a Noodle Shop ultimately to be (no pun intended) a misfire. This is yet another case where checking out the original and skipping the remake is the way to go.

I do not want to end on a purely negative note, though, so I will highlight a brief but wonderful moment in A Woman, a Gun, and a Noodle Shop. During one early scene, we watch shop employees Li, Zhao, and Chen prepare the dough that will become noodles. They do so by spinning the dough into a progressively bigger and bigger disc, whirling, flipping, and tossing it among themselves with the deftness of jugglers.

It is a fun, dazzling little sequence and the most successful introduction of a light-hearted element into the story. The noodle preparation scene prompts me to make an unsolicited recommendation to Zhang Yimou: in any future wuxia movies, the martial arts sequences should contain some cooking.