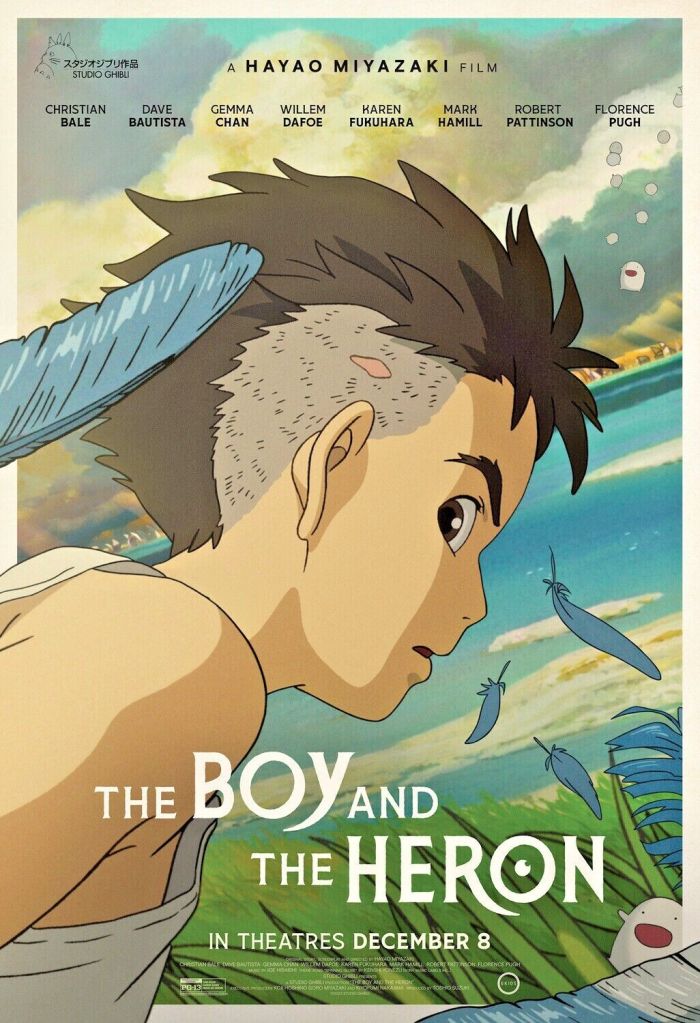

Here I review the long-awaited new movie from Hayao Miyazaki, The Boy and the Heron.

Returning from the longest of his many pseudo-retirements, Hayao Miyazaki has made his first movie in 10 years, The Boy and the Heron (2023).

The much-anticipated movie is a lovely work, boasting all the beauty, grotesqueness, and poignancy we have come to expect from Studio Ghibli’s most famous director. Overall, I would say it is Miyazaki’s best work since Spirited Away, which is probably the film it most closely resembles.

The Boy and the Heron, which Miyazaki also wrote, begins in Tokyo during World War II. In the frightening opening scenes, a boy named Mahito loses his mother in a hospital fire (the chronology suggests the fire might be the result of the Doolittle Raid, but the movie is vague about historical details).

The movie then flashes forward to a few years later. Mahito’s father has remarried. His new wife, Natsuko, is the younger sister of Mahito’s late mother and is pregnant. Mahito now must move from Tokyo to the countryside, to be close both to his father’s job and the ancestral home of his mother’s family.

Mahito keeps up a stoic exterior in the face of so much personal upheaval but is deeply unhappy. He resents his new stepmother, dislikes his new school, and his sleep is haunted by dreams of his mother.

The one aspect of life that rouses him out sullen withdrawal is an odd grey-blue heron that roams the swampy land around his home and seems to take an interest in him.

As the days pass, the heron variously flies close to him, raps on his bedroom window, and leads him to a crumbling stone tower near the house. (The abandoned tower was a project of Mahito’s eccentric great-great uncle, who vanished long ago.) Eventually the heron, with a mouth full of teeth, speaks to Mahito and tells him his mother is still alive.

The preternatural heron aside, these early passages of the movie are relatively grounded and showcase the quiet realism Studio Ghibli movies do so well. Scenes proceed at a deliberate pace, often with little dialogue, as we get a sense of daily life in this elegant family home amid the green countryside.

Mahito’s father works at an aircraft factory, Natsuko tries to be an attentive stepmother while battling morning sickness, and Mahito briefly attends school before a turn of events confines him to home for a while. Sharing the home with them is a group of elderly female relatives who are drawn in comically caricatured fashion, with over-large heads and exaggeratedly bent bodies.

One of the fiercer, more crotchety women is Kiriko, who is constantly trying to find a cigarette amid wartime rationing.

Characters’ movement amid their environment is rendered with the typical care Ghibli animators take to ensure two-dimensional drawings seem like real people and animals. I appreciated how a pedicab that Mahito and Natsuko take home from the local train station bends, wobbles, and creaks under their weight as they climb on board. I liked the naturalism of how the heron folds up its wings when it settles on a new perch and how Kirko, walking through the woods, reflexively recoils when a bent tree branch snaps back toward her. Probably best of all is how Mahito, after getting up in the middle of the night, carefully crawls backwards into his room on all fours so as to avoid making noises that will alert adults to his presence.

The movie also does a good job, sometimes through stylized visuals, of placing us in our young protagonist’s head. When Mahito runs through Tokyo trying to reach the hospital where his mother is, the fiery streets bend and blur around him, reflecting his panicked state.

When he watches his father and Natsuko from the top of the house’s stairs, we see the adults from his limited perspective as just shadows and pairs of feet moving about.

The Boy and the Heron’s story takes a crucial turn about half an hour in. Natsuko disappears suddenly, and Mahito suspects the heron is responsible. Reluctantly accompanied by Kiriko, the boy sets out to find the bird and his stepmother. His search leads him to an otherworldly realm, and this change in setting marks the movie’s transformation from a relatively realistic story with supernatural touches into pure fantasy.

The rest of the movie takes us through a variety of settings, from a windswept coast, to the open sea, to a jungle, to an underground labyrinth in which the stones carry electrical charges, to a strange yet familiar tower.

As Mahito travels through these settings, he meets the many denizens of this fantastical world: a flock of dangerously aggressive pelicans; a community of bear-sized parakeets who have taken aggressiveness a step further and organized into a militaristic society; a hardened but compassionate seafarer who is also named “Kiriko”; a species called the “warawara” who look like sentient balloons; a mysterious, ancient man; and Himi, a girl who can conjure up fire.

He also continues to encounter the heron, which seems to live a double existence of sorts and serves as a not-wholly-reliable guide for Mahito.

The fantastical passages of The Boy and the Heron proceed episodically, according to dream or fairy-tale logic. Lacking a clear plan for finding Natsuko, Mahito proceeds through his various encounters, accepting each situation and trying to make the best of it.

Miyazaki takes a similarly loose approach to this part of the movie. Little about the otherworldly realm and its inhabitants is ever clearly explained. Mahito seems to have entered a world that is beyond life and death yet is not precisely the afterlife either. Characters are similarly hard to pin down, often revealing new dimensions that prevent them from being categorized as simply either good or evil, trustworthy or duplicitous, knowable or unknowable.

I suspect how much you enjoy The Boy and the Heron will depend greatly on whether you can enjoy the serendipity and ambiguity of the story or find these features frustrating. Speaking for myself, I liked that the movie does not explain too much and allows the emotional or imaginative power of the various episodes to stand alone, unburdened by too much exposition.

Mahito’s magical odyssey touches lightly on such familiar Ghibli themes as humanity’s relationship to nature and the folly of war. The latter theme is reflected in the war-like parakeet society as well as the machismo of Mahito’s father (the parakeets and the father eventually cross paths in an amusing, mutually deflating encounter).

The heart of the story, though, is Mahito’s struggle with grief and loss and to accept how his life has changed. This aspect of the boy’s journey comes to a climax in two brief but deeply moving scenes late in the movie, in one of which Mahito makes a heart-felt confession and then in the other hears some heart-breaking yet reassuring words.

The Boy and the Heron is not just moving, though. It is also scary. While free of the violence found in Ghibli movies such as Princess Mononoke, the movie is full of disturbing situations and imagery and is likely to be frightening to children.

Several moments have a similar nightmare quality to the sequence in Spirited Away in which Chihiro’s parents are transformed into pigs. An unsettling visual motif that turns up repeatedly is of someone being smothered by swarms of animals or, in one scene, paper. (The movie also briefly dips into a vein of gross-out humor, similar to Chihiro’s encounter with the Stink Spirit, in a scene where Mahito must carve up a gigantic fish.) Parents of younger children should proceed with caution.

The score by the great Joe Hisaishi is quieter and more restrained than previous Ghibli music. Hisaishi provides no great themes but rather more meditative passages of music that nicely capture the story’s dreamy yet heartfelt quality. (Since I saw the movie in Japanese with subtitles, I cannot comment on the quality of the English dub.)

My favorite image from the movie is probably a serene, watercolor-like shot of Mahito and Kiriko the seafarer sailing across a becalmed sea. A runner-up would be a shot of Mahito walking across a sunlit colonnade that seems to be suspended in some ethereal state between worlds.

My choice for favorite humanizing detail would be a toss up between the above-mentioned moment of Mahito crawling backwards on all fours and a moment when the boy takes a drink and a single drop of water runs down his chin.

As I said, I think The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s best work since Spirited Away. While certainly not equal to Spirited Away—it lacks that movie’s sheer abundance of invention and Mahito is not as memorable a protagonist as Chihiro—the movie definitely deserves a place in the upper tiers of the Ghibli canon.

I have heard that Miyazaki may not go back into retirement but may make yet another movie. I wish him well and look forward to whatever he does next. For the time being, though, I am simply grateful that, now in his 80s, he came back to film-making and created as lovely and touching a movie as this one. That is the most magical part of all.

Leave a comment