Here I look at one of the most talked-about movies of the year, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer.

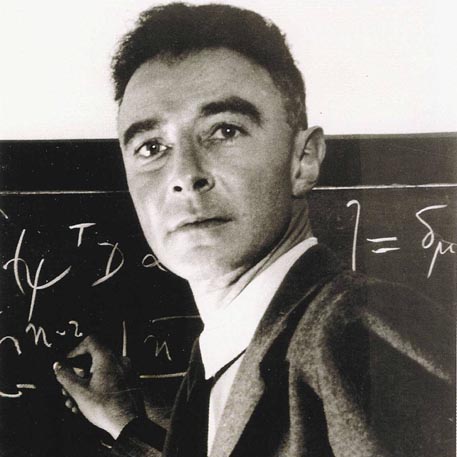

The life and career of J. Robert Oppenheimer seem tailor-made for dramatization. A brilliant theoretical physicist who taught at the University of California-Berkeley (he helped infer the existence of black holes decades before they were discovered), Oppenheimer is best known for serving in the 1940s as director of research at the US government laboratory at Los Alamos, New Mexico, that built the first atomic bombs. Oppenheimer and his colleagues created the original atomic bomb that was exploded in the Trinity test and the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Although his atomic bomb work made him one of the most famous scientists in the world, Oppenheimer later paid a career price in the 1950s. A complicated mix of professional rivalry, Cold War-era concerns about Oppenheimer’s Communist associations (about which the scientist had given misleading statements), and Oppenheimer’s growing unease with the nuclear arms race led to him being quasi-blacklisted. He was stripped of his government security clearance and retreated from public life in his remaining years.

Oppenheimer’s biography thus offers a window into some of the 20th century’s most dramatic episodes: World War II, the atomic bombings of Japan, and the Cold War and Red Scare. His life also offers a familiar, irresistible narrative: a brilliant man whose most impressive achievement later contributes to his own downfall. Kai Bird and the late Martin J. Sherwin aptly called their Oppenheimer biography American Prometheus, after the titan who stole fire from the gods and paid a terrible price. The scientist’s life also echoes such tales as the Lion-Makers, the Sorcerer’s Apprentice, and Frankenstein (another latter-day Prometheus story).

This complicated, eventful story has now received a cinematic dramatization in Oppenheimer, written and directed by Christopher Nolan. The resulting movie certainly captures the fable-like quality of the scientist’s story, in which “The spirits, whom I’ve careless raised/Are spellbound to my power not.” Yet Nolan adds another dimension to this narrative, portraying Oppenheimer as a man whose destructive and self-destructive tendencies flowed from a fascination with chaos and even death.

As written by Nolan and played by Cillian Murphy, Oppenheimer is a psychologically troubled man fixated on quantum physics’ revelation of a reality behind the everyday world, in which the usual rules do not apply. An early sequence neatly captures this obsession with upending the accepted order by juxtaposing the young Oppenheimer’s study of quantum physics with his contemplation of the fractured perspective in a Picasso painting. His theorizing about black holes is another facet of a concern with entropy and collapse. On a personal level, Oppenheimer’s fixation with disorder leads him to pursue relationships with two troubled women and perhaps (in a mysterious incident) to attempt to poison one of his university professors.

In this interpretation, Oppenheimer’s contribution to the most destructive weapons in history is simply the most consequential expression of his larger obsession. J. Robert Oppenheimer becomes the morbid romantic on a grand historical scale.

The movie dramatizing this historically and psychologically weighty story requires careful, sustained attention. Running to three hours, with perhaps two dozen significant characters, Oppenheimer is packed full of important information: indeed, the first 45 minutes to hour is mostly exposition.

The dense story is further complicated by Nolan’s penchant for jumping back and forth in time within a narrative. In Oppenheimer, this non-linear approach takes the form of a double framing device. The movie provides parallel plot threads of Oppenheimer defending himself before an Atomic Energy Commission panel reviewing his security clearance and of former AEC Chair Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) defending his treatment of Oppenheimer before a congressional hearing. As the two antagonists recount their respective versions of events (with the Oppenheimer story-line presented in color and the Strauss one in black and white), the movie flashes back to Oppenheimer’s past career, including the building of the atomic bomb.

Despite all these demands on the audience, Oppenheimer succeeds as a story and successfully conveys both Nolan’s conception of the scientist and the horrifying threat of nuclear weapons.

The screenplay compensates for the massive quantity of events and information the movie must cover by typically keeping scenes short. Each episode delivers the necessary plot or character points and then we are on to the next episode. The dialogue is similarly tight, communicating essential information with a minimum of verbal padding. This approach gives the movie forward momentum and generally prevents it from dragging. At its best, the dialogue even resembles the rapid-fire repartee characteristic of 1940s-era movies.

Oppenheimer’s heart is the passages dealing with the atomic bombs’ construction at Los Alamos. While the movie does not delve deeply into the technical side of the construction, it provides enough information for viewers to grasp the basics: a story-telling device involving a goldfish bowl and a cocktail glass is used effectively to convey the bombs’ progress to viewers. These scenes generate thriller-like suspense as Oppenheimer and the other scientists involved in the project approach the dreadful day of the bombs’ creation.

Christopher Nolan is known for filming in IMAX, and the work of Oppenheimer‘s cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema certainly looks impressive on an IMAX screen. The New Mexico landscapes of Los Alamos and its surroundings are appropriately grand yet desolate in the movie. On a subtler level of visual storytelling, Oppenheimer uses an apt recurring motif of rain falling on water: the tiny particles causing larger ripples provide a neat metaphor for the various chain reactions that concern the movie’s protagonist.

Even more impressive than its visuals, however, is Oppenheimer’s use of sound. Nolan and his sound designers know precisely when to go loud and when to go quiet, when to use sound and when to use silence. Along with the recurring visual motif of rain, they use a still more powerful aural motif: the sound of feet drumming on a floor. This very ordinary sound is put to terrifying use in the movie.

The filmmakers’ use of visuals and sound reach a climax in Oppenheimer’s portrayals of the July 1945 Trinity test of the first atomic bomb and of the subsequent bombings of Japan.

The portrayal of the test is appropriately frightening yet fascinating. Nolan and his visual effects team famously declined to use CGI to recreate the atomic detonation, instead relying on practical effects. Their efforts paid off: the resulting explosion looks impressive. As with the rest of the movie, though, what is more crucial to the episode is the use of sound. The contrast between what is seen and heard (and not heard) gives the scene tremendous power.

The movie’s re-creation of the test conveys how Oppenheimer’s obsessions and work have culminated in something both awesome and monstrous. In this vein, I also appreciated a subdued yet striking moment before the Trinity test when Oppenheimer simply stands in front of the bomb in an attitude that seems both mournful and reverential.

Nolan chooses not to show the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings directly on screen. Nevertheless, the bombings and their victims are very much present in several eerie scenes where Oppenheimer contemplates the significance of his work. One scene, in which Oppenheimer addresses the other Los Alamos team members, again uses sound and visual effects to drive its agonizing point home. A later scene, where Oppenheimer meets with President Harry S Truman (Gary Oldman), manages, through staging and dialogue, to be quietly devastating.

Oppenheimer slackens somewhat in its final act dealing with Oppenheimer’s blacklisting, which is inevitably a less absorbing topic than the bomb’s construction and use. Nevertheless, the movie ultimately justifies this focus on the scientist’s post-war troubles. Both the scenes with Oppenheimer before the AEC panel and with Strauss before Congress provide a way to cross-examine Oppenheimer’s actions and highlight his responsibility for the atomic bombings and the nuclear threat we all live under today.

The weakest part of the movie is its handling of Oppenheimer’s relationship with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), an aspiring psychiatrist and Communist with whom he had an extra-marital affair. Although largely historically accurate and important on both a plot and character level, the affair subplot is treated in too perfunctory a way to be very interesting.

This subplot also leads to the two worst scenes in the movie. In one, Oppenheimer quotes a famous Bhagavad-Gita passage while having sex with Tatlock. This touch is apparently meant to illustrate the “in love with death” theme but ends up just being deeply silly. The use of the quotation in this odd context robs some of the power from a later, far more famous, episode when Oppenheimer quotes the passage.

In the other bad scene, Oppenheimer’s wife Kitty (Emily Blunt) is confronted with her husband’s infidelity in a moment that could have worked but that Nolan handles in such a ham-fisted way as to drain away any potential power.

The Tatlock story thread takes up relatively little screen time, though, and is more a minor flaw than a serious problem with the movie.

Cillian Murphy, with his gaunt face and large eyes, looks reasonably like the real Oppenheimer and gives a subtle performance as the scientist. Murphy plays the role with a reserve that comes across, depending on context, as arrogant, diffident, or haunted, which are all appropriate notes to play for Oppenheimer. Matt Damon is excellent as General Leslie Groves, the commander of the atomic bomb project. Damon brings an aggressiveness and emotional bluntness to Groves that contrasts well with Murphy’s aloof performance. The scenes featuring Oppenheimer and Groves are among the liveliest in the movie.

As Lewis Strauss, Robert Downey Jr. does an interesting riff on his usual movie persona, presenting a character no less intelligent and articulate than his other roles but with a complete, pitiless absence of humor. As the hard-drinking Kitty Oppenheimer, Emily Blunt has sadly little to do but still manages to convey multiple dimensions to her underwritten role. The conflict between Kitty’s brutal pragmatism and her husband’s scruples also helps to underline the movie’s themes.

Among the strong supporting cast, two standouts for me were David Krumholtz and Benny Safdie as, respectively, physicists I. I. Rabi and Edward Teller. Heavy-set, proletarian, and commonsensical, Krumholtz’s Rabi is the perfect Sancho Panza figure to Oppenheimer’s Don Quixote. Safdie has a more challenging role: Teller is a controversial figure, both because of his role in Oppenheimer’s blacklisting and his work creating the hydrogen bomb–he was one of the inspirations for Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. Yet Safdie and Nolan’s screenplay, while acknowledging Teller’s Strangelovian qualities, do not take the easy route of portraying the physicist as a simplistic villain but rather present him as a temperamental, complex human being.

In a movie filled with memorable and powerful incidents, Nolan saves the most powerful moment for the final scene. At the close, the full significance for humanity of what Oppenheimer and his colleagues wrought so many years ago is revealed. I hope many, many people—especially policymakers in Washington, Moscow, Beijing, and elsewhere—see and remember this conclusion.

Post-Script: Oppenheimer has provoked an interesting discussion of whether Nolan should have directly portrayed the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings and whether he erred by not giving a face to the Japanese victims of the bombings. For an excellent analysis of this issue, see the Like Stories of Old video on the topic.

For my part, I can see both sides of the argument. Censoring or softening the presentation of real-world violence does seem questionable, especially if viewers might not be familiar with the historical reality involved and might need to be confronted with it to fully appreciate its horror. At the same time, I appreciate that violence can be presented indirectly or non-literally and still be powerful, while graphic violence can just cause people to look away–or, worse, to look for the wrong reasons.

I think Christopher Nolan’s approach in Oppenheimer was a valid one. Nevertheless, for the sake of presenting a more rounded perspective on the bombings, I will look in the coming months at some notable movies that have presented the Japanese perspective on this subject in various ways.

A version of this review originally appeared on the Rehumanize International blog.