Next in my Zhang Yimou retrospective, I look at House of Flying Daggers.

House of Flying Daggers (2004) is Zhang Yimou’s second wuxia movie, and it raises the pressing question: “Does the movie live up to that title?”

The answer is no, not quite (could any movie?). It comes close, though.

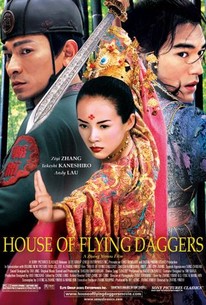

Co-written by Zhang with Li Feng and Wang Bin, House of Flying Daggers begins like a Chinese Robin Hood tale. Set in the 9th century, amid the corrupt and faltering Tang dynasty, the movie shows us local law enforcement under Captain Leo (Andy Lau) working to suppress the titular House, a secret society dedicated to stealing from the rich to give to the poor and otherwise defying authority.

(So, I am afraid I must report the movie does not feature a death-trap-like house in which daggers spring from the walls. Yes, that was probably my chief disappointment as well.)

Among Captain Leo’s men is Jin (Takeshi Kaneshiro), an insouciant fellow with a reputation as a womanizer. Leo gives Jin an assignment seemingly well-suited to him: to infiltrate a brothel where a member of the House of Flying Daggers is said to be secretly working. Jin goes, posing as a client, and it soon emerges that the House agent disguised as a courtesan is a young woman named Mei (Zhang Ziyi). Mei is blind yet no less devastating in combat because of it.

After apprehending Mei, Leo and Jin cook up an elaborate scheme to use her to draw out the rest of the House of Flying Daggers. Before long, Jin and Mei are traveling together on a journey that might lead them to the young woman’s comrades. The situation becomes more complicated as Jin and Mei start to develop what might be feelings for each other.

Little is simple in the House of Flying Daggers, however, and as the story continues it becomes clear that the characters, their situations, and their relationships are often not what they seem. Revelations, reversals, and betrayals abound, punctuated by periodic martial-arts set-pieces.

Along with stunt work, Zhang uses CGI in these action set-pieces, relying on it to a greater degree than in his previous wuxia movie, Hero. He uses computer effects specifically to highlight characters’ preternatural marksmanship, particularly how members of the House of Flying Daggers employ the throwing knives that give the society its name.

The camera seems to follow individual daggers, arrows, or other weapons, traveling with them as they hurdle through the air toward their targets. The effect hardly looks realistic, but it emphasizes the combatants’ skill and provides heightened clarity to the action sequences: in a confrontation, viewers can see where each projectile is and where it is going.

Two action sequences in particular stand out for their memorable staging. One, set in a bamboo forest, features characters fleeing from a unique type of human wave attack. Another is a climactic duel in which Zhang sets aside dance-like elegance and goes for visceral force, using staccato editing to convey the violence of the fight and including plenty of close-ups to highlight the duelists’ mutual hatred.

Fine though the fight choreography is, though, House of Flying Daggers’ chief visual treat, as in most Zhang movies, is the stunning array of colors on display. Both cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding and costume designer Emi Wada do excellent work.

Most of the movie takes place outdoors, so we witness the profound green of the bamboo forest; the mixed greens, yellows, and reds of another forest slowly entering autumn; the golden shine of an open field of grass and wildflowers; and the white of birches and snow.

The costumes are no less splendid, from Mei’s courtesan robes and their long sleeves, Jin’s deep blue-purple clothes, or the costumes of the Flying Daggers members, which rival the bamboo trees for vivid green.

We get to savor these natural and human-made sights because alongside the action pyrotechnics Zhang and Zhao also give us quiet moments and the painterly images that often fill Zhang’s movies.

The principal actors all do good work. Zhang Ziyi burns with intensity: when her face is suffused with hatred or she sheds a tear, you believe the emotion. Takeshi Kaneshiro plays Jin with a superficial self-confidence undercut by naivete; the handsome young warrior turns out to be something of an innocent amid the surrounding intrigue. In supporting roles, both Andy Lau and Song Dandan are called upon to play very different notes at different points in the story and do so effectively.

Good as House of Flying Daggers is, I must acknowledge I did not enjoy it quite as much as Hero. Various minor issues hamper the movie. For all the beauty of the landscapes, the basic situation remains a relatively static one for most of the run-time: people travel or chase each other through the countryside. Some of the plot twists become repetitive: late in the movie, we get two remarkably similar back-to-back scenes between pairs of characters. The action scenes are not quite as plentiful as in Hero, which leads to the plot dragging at times.

Still, being as good as Hero is a high standard to meet, so I cannot fault Zhang and his team for not matching their earlier achievement. As it is, House of Flying Daggers is a well-made action melodrama with plenty of the operatic style one would hope for in such a work. That is an accomplishment to be proud of as well.

Leave a comment