Two movies, made almost 30 years apart, offer two different interpretations of the same fanciful, melancholy book. In this review, I look at Night on the Galactic Railroad and Giovanni’s Island.

Night on the Galactic Railroad, sometimes also translated as Milky Way Railroad, is a book by schoolteacher, poet, and children’s author Kenji Miyazawa (1896-1933). The book was probably written around 1927, although it was never finished and was published posthumously.

A fable-like tale, Night on the Galactic Railroad follows a poor young boy named Giovanni. With his fisherman father away from home and his mother ailing, Giovanni must work various before- and after-school jobs to help support his family. Because of his poverty, his schoolmates bully him, but Giovanni has one friend, a boy named Campanella.

On the night of the Milky Way Festival (Japan’s Tanabata Festival), Giovanni runs out on an errand and soon finds himself traveling on a magical train. The train travels through the Milky Way, passing by or stopping at such celestial bodies as the Northern and Southern Crosses, the Swan, and the Scorpion. Campanella turns up on the train as well. The two boys ride together on a journey rich with symbolism and allusions: a church-like atmosphere marks the Northern and Southern Crosses, for example, while beautiful music emanates from the Lyra (Harp) constellation.

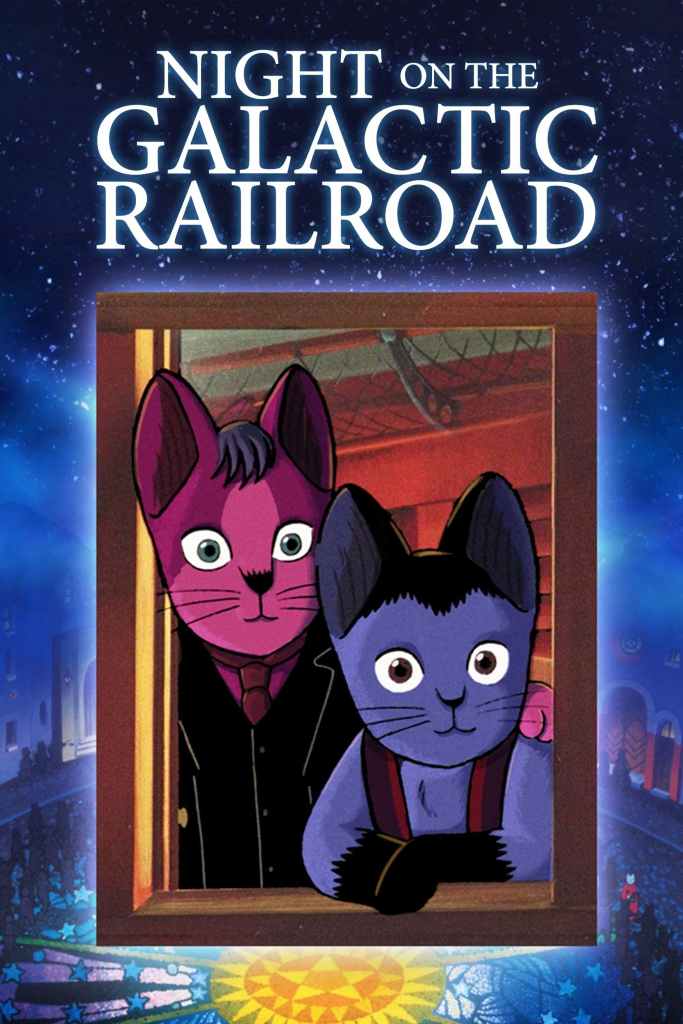

This unusual children’s book has inspired other works of art, including two animated movies. Night on the Galactic Railroad (1985) is a faithful adaptation of Miyazawa’s story. Giovanni’s Island (2014) is a substantially different story that nevertheless refers to and parallels the original book in crucial respects.

The two movies offer an intriguing study in contrasts. Night on the Galactic Railroad is ambitious and creative, yet also emotionally cold. Giovanni’s Island has a far more conventional narrative and visual style yet is also far more moving. Both deal in weighty themes such as loss.

Directed by Gisaburô Sugii, from a screenplay by Minoru Betsuyaku, Night on the Galactic Railroad closely follows the plot of Miyazawa’s book while introducing some significant new features.

The adaptation’s most obvious distinct feature is that, while in the book all the characters are presumably meant to be human, the movie is set in a world of anthropomorphic cats. Giovanni, Campanella, and most of the other characters are all feline in form here, with Giovanni’s simple vest and Campanella’s coat and tie serving to identify their differing class backgrounds.

Another difference is that while in the book the characters’ Italian names are just a universalizing touch to an otherwise Japanese setting, the movie sets the early scenes of school and village life amid appropriately Mediterranean-looking buildings, piazzas, and hills.

The animation relies on simple, clear draftsmanship and often uses rich, dark colors. Several landscapes and cityscapes reminded me of a kind of Italianate version of Edward Hopper’s paintings. This impression was only strengthened when the celestial train passes through a Middle American-style cornfield.

The train ride gives us several surreal images and sequences. On their journey, Giovanni and Campanella visit a paleontological dig within a landscape that seems to be one vast skeleton of a prehistoric beast. At another point, they walk through a petrified, crumbling ghost town. At still another, they descend a seemingly never-ending staircase in the middle of a void.

One of the boys’ fellow passengers is a bird catcher whose wrangling of herons is portrayed with a dance-like grandeur. Also joining them for the train ride are a pair of children and their young tutor (notably these three are among the few human characters in the movie).

The circumstances surrounding the trio’s arrival on and departure from the train produce scenes that are both awe-inspiring and poignant.

After the use of anthropomorphic cats, the most notable stylistic choice Sugii and his team make in Night on the Galactic Railroad is to embrace the scary, unnerving possibilities of this story.

This choice is apparent in the movie’s oddly deliberate pace. Mundane early scenes such as Giovanni working an after-school job in a printing press or buying some groceries at a local store play out at unusual length, with little dialogue or music. Rather than being boring, though, the effect (at least for me) is to create a sense of tension, as though the scene is building to some terrible, violent climax.

A multitude of other details included by the filmmakers contribute to this unsettling atmosphere: a persistently ringing phone that no one ever answers; an ominous comment muttered by a villager leaving a shop; the fact Giovanni’s invalid mother is never shown on screen but is simply a voice calling from a darkened bedroom; and the way passengers aboard the train often appear in unexpected ways or simply materialize out of the air.

The movie also emphasizes the grotesqueness of certain characters and the possible menace of certain situations. The train conductor, seen from young Giovanni’s perspective, looks like a giant as he looms over the boy. The conductor’s enormous hand, reaching out for a ticket Giovanni might not be able to produce, is almost a character in its own right. When Giovanni goes on a night-time errand to get milk for his mother, the scene’s staging—the lonely path leading to the dairy, the dairy’s darkened interior, and the wraith-like appearance of the establishment’s sole occupant—turn what is, on a plot level, just a functional scene into a nail-biter.

I do not know if this tonal approach to the story is the best one, but the movie is certainly memorable as a result. A sense of quiet dread pervades even scenes in which little is happening.

Here, though, we come to Night on the Galactic Railroad’s weaknesses. The visuals and foreboding tone, though effective, cannot wholly cover up the dramatically slack story. Like Miyazawa’s book, the movie is just a series of fantastical episodes that finally ends with a twist that can be seen all the way down the railroad.

To be fair, I am not sure the movie’s ending is even meant to be a “twist,” given how explicitly the events and dialogue telegraph what is coming. Also, the climactic scene is still moving despite being predictable. Even making such allowances, though, watching a slight plot play out slowly to an inevitable conclusion is not quite a satisfying experience.

The movie’s events do not have as much emotional impact as perhaps the filmmakers intended. Given how dream-like and stylized everything is, I found it hard to relate to the characters or be touched by what happens to them. While Night on the Galactic Railroad does have a certain power, it is an abstract power arising from the underlying scenario rather than any strong identification with Giovanni, Campanella, and other passengers on the train.

In contrast to the fantastical setting of Night on the Galactic Railroad, Giovanni’s Island uses real-life history as its backdrop. Directed by Mizuho Nishikubo, from a screenplay by Shigemichi Sugita, Wendee Lee, and Yoshiki Sakurai, Giovanni’s Island is set in the late 1940s and covers a dimension of World War II that is probably little known to most western audiences.

The story follows adolescent boy Junpei and his younger brother Kanta. The two boys live with their widowed father and extended family on Shikotan, a small island in the Kurils, in Japan’s far north. The two boys know and love Miyazawa’s Night on the Galactic Railroad, which was a favorite of their late mother, and the movie contains numerous quotations from and allusions to the book.

The brothers’ island home is too remote to be directly affected by the war, but after the war ends the inhabitants must deal with foreign occupation: in this case, by the Soviet Union.

Junpei and Kanta soon find their house repossessed by the Soviet commander and his family, while they must relocate to a stable. Their schoolhouse is divided between the native inhabitants and the children of the Soviet soldiers. As the occupation continues, food and other goods become scarcer.

Yet daily life continues even under foreign military occupation, and the two brothers, who do not fully understand what the occupation means, find ways to enjoy themselves. Despite language barriers, they start playing with their new Russian classmates.

Most important, they befriend Tanya, the daughter of the Soviet commander who now lives in their old house. Reasoning, as Junpei notes, that she won’t understand their Japanese names anyway, they take their cue from the Miyazawa book and introduce themselves to her as “Giovanni” and “Campanella.” In keeping with the Miyazawa influence, a shared toy train set also serves as a bond between the brothers and Tanya.

Giovanni’s Island has an animation style that comes across as both simple and sophisticated at once. The draftsmanship, done in pastels, has a soft, sketchbook appearance: one can see individual pencil strokes etched in the images on screen. This style is a good way both to convey the beauties of rural Shikotan, with its green hills, sandy cliffs, and surrounding ocean, and to reflect the young protagonists’ sensibilities.

Despite the simplicity of the imagery, the movement of characters and perspective is quick and fluid. Moreover, the realistic scenes of life on Shikotan are complemented by highly stylized sequences set among the stars that recreate and dramatize moments from Night on the Galactic Railroad.

The filmmakers handle the movie’s complicated subject matter with care. Serious conflicts between the island’s adult residents and the Soviet occupiers are presented on screen: Junpei and Kanta’s father in particular, being a leader of Shikotan’s community, finds himself at odds with the Soviets. Nevertheless, for much of the movie these weightier matters are in the background. The focus is how the occupation affects the young protagonists, sometimes in unexpected ways. Through this child’s-eye view of foreign occupation, Giovanni’s Island shows how ordinary life goes on and can contain happy experiences, even while constant menace looms over the characters.

The movie’s ability to hit different notes simultaneously is apparent in an early scene of an encounter between Junpei and the occupiers. The boy is attending class in Shikotan’s rather ramshackle schoolhouse when a group of Soviet soldiers, armed with rifles and machine guns, bursts into the classroom. The teacher is shaken but tries to continue with class and asks Junpei to solve a math problem at the blackboard. As Junpei goes up to the board, one of the soldiers seems like he might shoot. Violence is averted when the troops’ commander arrives and approaches Junpei and his teacher. The Soviet commander takes a piece of chalk and solves the problem on the blackboard, wordlessly tapping the board to indicate the correct answer before handing the chalk back to Junpei. The soldiers then move on from the classroom. As the tension dissipates, we get a shot of Junpei that tilts down to reveal the boy has wet his pants in fear.

As Russian students move into the schoolhouse, the native students develop an ambivalent relationship with their colonizing peers. The school’s Japanese and Russian students begin a practice of each singing during the school day in their respective languages. This singing starts out as a competition between the two students groups but then takes a different turn. A similar change unfolds for Junpei and Kanta specifically: the Soviets initially appear to them as grotesque giants but as they get to know Tanya and eat and even dance with her family, their perceptions change.

These scenes of life on occupied Shikotan also contain some well-observed character details. I appreciated the touch that while most of the Japanese students in this humble community wear ordinary clothes to school, Junpei, as the son of a community leader, wears a formal uniform. When Tanya discovers that Junpei has been drawing pictures of her, her reaction to this incipient crush is amusingly direct: she is obviously pleased and immediately poses so he can draw another picture.

Giovanni’s Island shifts dramatically in story and tone about halfway through, when the Shikotan community must face changed circumstances. In response, Junpei and Kanta go on an odyssey that involves great danger and sacrifice. These later passages of the movie also contain clear parallels with the Miyazawa story.

While the brothers’ dangerous journey is suspenseful, I found the second half of the movie somewhat less absorbing than the first. The later sections lack the nuance and varied tones of the earlier, more slice-of-life scenes of occupation. Nevertheless, certain moments still land powerfully, as when a group of travelers arrive in what is revealed to be a far grimmer destination than they expected.

The climax of Giovanni’s Island involves a tragedy that may strike viewers as either heart-breaking or painfully manipulative. I found it a mixture of both, and the movie perhaps could have benefited from a subtler approach—although I acknowledge that the climactic tragic event is in keeping with the Night on the Galactic Railroad story.

Whatever the flaws of its later sections, though, Giovanni’s Island ends beautifully. The final scene gives us an epilogue to Junpei, Kanta, and Tanya’s story that blends sorrow and regret with reconciliation and hope in a way I found deeply moving.

Night on the Galactic Railroad and Giovanni’s Island are very different movies, yet they share an ability to haunt the viewer. Each is a memorable tribute to Kenji Miyazawa’s original book.

Part of this review originally appeared on the Consistent Life Network blog.

Leave a comment