Continuing my Zhang Yimou retrospective, I look at Hero.

Hero (2002) is Zhang Yimou’s first entry in the wuxia genre, and it is a cracker: a fast-paced, visually sumptuous action movie that offers viewers all the duels, beautiful locations, and dramatic poses they could desire.

Co-written by Zhang, Li Feng, and Wang Bin, Hero is set in the 3rd century B.C.E., during the reign of Qin Shi Huangdi, regarded as China’s first emperor. Best known in the west for the army of terracotta warriors that adorned his tomb, Qin Shi Huangdi conquered China’s various feuding states and brought unity to the land—although at the cost of extreme repression.

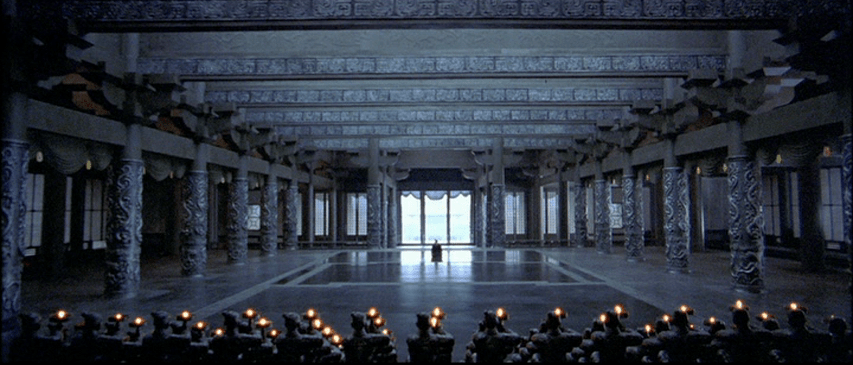

The movie begins with the emperor (played with an appropriate mixture of arrogance and Machiavellian shrewdness by Chen Dao Ming) hosting a guest within his vast palace. The guest is an anonymous, orphaned warrior known simply as “Nameless” (Jet Li).

Nameless claims to have vanquished three legendary warriors who posed a threat to the emperor. Qin Shih Huangdi, who lives in constant fear of assassination, is seemingly interested both in rewarding the man who has removed a danger to him and in discovering how he defeated such formidable opponents.

The conversation between Nameless and the emperor provides the framing device for Hero, which unfolds largely in a series of flashbacks to Nameless’ encounters with the other three warriors, known as Sky (Donnie Yen), Flying Snow (Maggie Cheung, billed here as Maggie Cheung Man-Yuk), and Broken Sword (Tony Leung, billed here as Tony Leung Chiu-Wai). As the imperial interrogation, set in a cavernous throne room, continues, it becomes apparent that there is more to Nameless’ story than the warrior initially lets on. We subsequently see past events played out more than once, in different ways.

If one word sums up Hero, it is “flamboyant.” In keeping with the story’s epic, myth-like quality, Zhang does not bother with subtlety but always goes for maximum effect. This is the kind of movie where drapery and characters’ clothes billow dramatically in the wind at every opportunity, where sunlight flashes on swords as if on cue, and where lines like “Since you want to die, I shall assist you” seem appropriate.

Zhang has always been bold in his use of color, but here he and cinematographer Christopher Doyle all but hurl strong colors against the screen. The movie adopts the stylized conceit of having one strong color be dominant in each distinct setting.

Qin Shi Huangdi’s palace is shrouded in dark black, from the walls and floors to the armor worn by the emperor and his courtiers and guards.

A calligraphy school described by Nameless is awash in blood red, provided by both the school’s décor and the students’ robes. Later, we return to the same setting and characters but now everything is celestial blue.

A wooded grove is presented as a riot of delicately yellow autumnal leaves. In a sun-bleached desert, everyone wears immaculate white.

Composition is similarly aggressive in its artistry. Again, Zhang has always had a knack for striking shots, but the shots here draw attention to themselves in a way not seen in his past movies.

Framing of characters is often perfectly symmetrical, with the actors speaking directly into camera. Contrasts, whether between colors or characters and objects on screen, are stark. Consider how Flying Snow, in her red robes, is placed against the yellow of the grove. Or consider a shot of Flying Snow, Broken Sword, and a calligraphy box and how they occupy the foreground and background of the shot.

Hero boasts more fight scenes than I can count, and all are memorable in some way. As in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, the various duelists leap around and clash with each other with a balletic grace that is hypnotic to watch. And, as in the earlier movie’s duels, the fighters can fly and perform other feats that defy physical laws.

My favorite duels are probably a fight in the rain between Nameless and Sky (which gives the otherwise sadly under-used Donnie Yen a chance to show his skills) and one involving Broken Sword set in a chamber hung with curtains. I would give an honorable mention to a duel in the yellow wooded grove between Flying Snow and the young Moon (played by Crouching Tiger’s Zhang Ziyi).

The different fights in Hero usually contain some distinct feature, in addition to the different settings and colors, to set them apart. The Nameless vs. Sky duel involves a sequence in which we get a glimpse into the opponents’ minds as they play out each other’s tactics and the probable course of the fight beforehand. The Broken Sword duel in the chamber uses the curtains to create a maze-like effect, as the opponents dance around each other, appearing and disappearing. In the wooded grove duel, Flying Snow uses her preternatural abilities to make the wind and leaves an ally against Moon.

In keeping with the dance-like quality of the action sequences, a theme of Hero’s action choreography is synchronization. An army assembling for battle or courtiers rushing into the emperor’s throne room move artfully in time together. In a scene where Nameless demonstrates his martial prowess, we get an impressive display of synchronized movement from some inanimate objects. The duel with Broken Sword in the curtained room includes a similarly grin-inducing moment.

If I have a quibble with Zhang’s approach to the action set pieces, it is that he favors their sheer spectacle over showcasing the stunt fighting. The focus on lavish sets and costumes and the fancy camera work—frequent use of slow motion, unusual camera angles—prevent the movie from giving us clear, unbroken views of the fighters for any great length of time. I would have liked the opportunity just to sit and watch great stunt people do their work for a bit. Also, some of the effects, such as early 2000s-era CGI, look less-than-impressive today.

Still, these quibbles are just that, nothing more. If the action set pieces are mainly opportunities to create memorable images, I thoroughly enjoyed them on that level. Watching beautiful people, clothes, drapery, and other objects fly and tumble about each other, all rendered in breath-taking colors, provides a pleasure all its own.

The use of slow-motion similarly helps sometimes both to clarify the fighters’ actions and underline their power. Sometimes Zhang’s cinematic tricks work quite well in these sequences. I appreciated the awesome grandeur of the overhead shot of two white-clad duelists flipping about each other against a dark background, forming a kind of living yin-yang symbol.

Characterization is kept simple, which works fine for this larger-than-life story. As Nameless, Jet Li is aptly mysterious and self-contained. Flying Snow and Broken Sword are not merely comrades in arms but lovers with a stormy past. The tensions in their relationship are the most emotion-laden aspect of the movie, and Maggie Cheung’s fiery performance balances well with Tony Leung’s more brooding smolder. As Moon, Zhang Ziyi reminded me of her knack for conveying intense emotions without saying a word.

I preferred Hero to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon because the conflicting stakes—love, revenge, freedom, stability—are clearer and more potent, while the story is simpler and moves directly and swiftly to its climax. Both movies have tragic endings, yet I appreciated the tragedy in Hero more. A sad ending can be satisfying as long as it is the right one for the story. For this mythic tale, the ending is apt.

Is the ending depressing? No more so than when Achilles dies from Paris’ arrow or Arthur is mortally wounded by Mordred. Far from being depressing, meeting one’s inevitable destiny in a grandiose fashion is the mark of a classic hero.

Leave a comment