Before continuing my Zhang Yimou retrospective, I must take a quick detour to a seminal movie in the genre that would define the next stage in Zhang’s career: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

Zhang Yimou broke into a new artistic realm in the early 21st century. Having made his name with historical family dramas and off-beat, cinema-verité-style features, Zhang made a string of movies in the 2000s that belonged to the new (for him) genre of wuxia.

Wuxia, which can translated as “martial hero,” is a very old type of fiction in Chinese literature and cinema. Wuxia stories revolve around the adventures of independent, wandering warriors. In their travels, these warriors often must fight against some injustice.

As Jeanette Ng describes the genre,

The archetypal wuxia hero is someone carving out his own path in the world of rivers and lakes, cleaving only to their own personal code of honour. These heroes are inevitably embroiled in personal vengeance and familial intrigue, even as they yearn for freedom and seek to better their own skills within the martial arts. What we remember of these stories are the tournaments, the bamboo grove duels and the forbidden love.

In China, wuxia is roughly analogous to Japanese tales of samurai, European romances about knights errant, and American westerns.

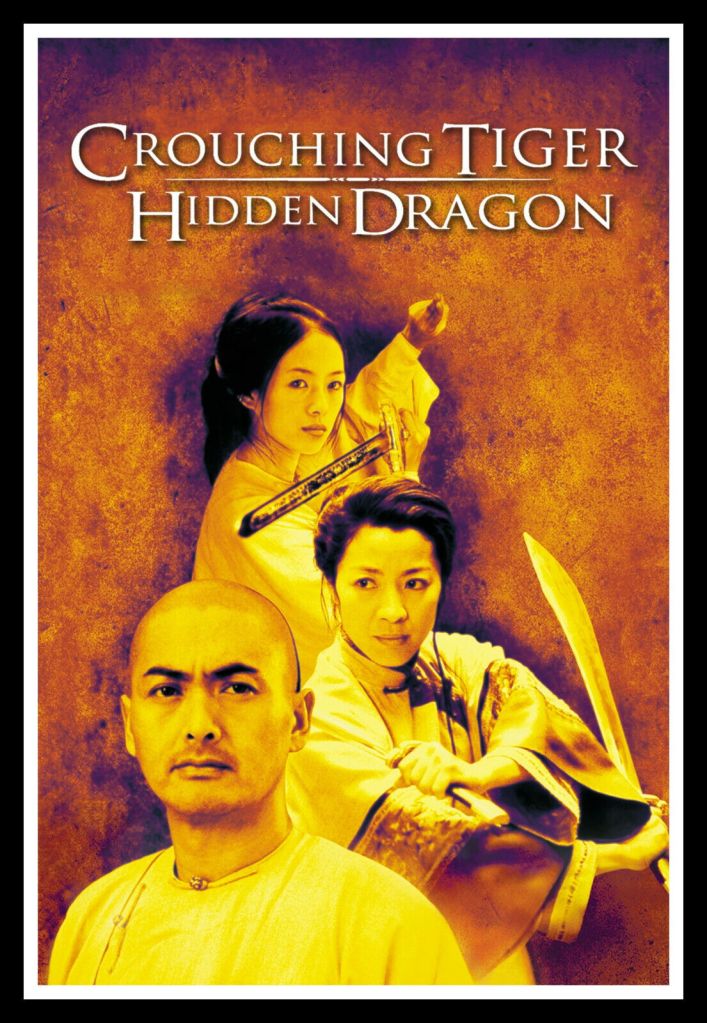

Before I could discuss Zhang’s contributions to wuxia cinema, though, I felt I had to give due attention to an earlier movie that introduced many western audiences to wuxia and helped convince Zhang that his own contributions to the genre could be commercially successful. I am referring of course to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000).

Directed by Taiwan-based filmmaker Ang Lee and written by Wang Hui Ling, James Schamus, and Tsai Kuo Jung (from a 1940s-era novel by Wang Du Lu), Crouching Tiger is set in China sometime during the Qing Dynasty (1636-1912).

The story begins with Master Li Mu Bai (Chow Yun Fat), a warrior who has grown discontented with his way of life and is seeking something different, perhaps a more spiritual path. Li visits his old friend and comrade in arms Shu Lien (played by 2023 Best Actress Oscar Winner Michelle Yeoh), who now runs a martial arts school and shipping business.

As part of his spiritual quest, Li has decided to give up his sword, the ancient and powerful Green Sword of Destiny. He entrusts the sword to Shu Lien, asking her to take it to Peking for safekeeping in an elderly aristocrat’s home. In addition to setting up this mission, these early scenes also establish that Li Mu Bai and Shu Lien have strong but unexpressed feelings for each other.

Shu Lien takes the sword to Peking as charged. At the aristocrat’s home, she meets another guest, a willful young woman named Jen (Zhang Ziyi). Although betrothed to be married, Jen has other plans for her future, longing to become an independent warrior like Li Mai Bai and Shu Lien. In keeping with her ambition, she is soon revealed to be a preternaturally gifted martial arts fighter.

Also in Peking is a police inspector and his daughter, who are pursuing the mysterious Jade Fox, a female outlaw who has done them a wrong. Li also has an interest in this pursuit, having a score of his own to settle with Jade Fox.

Before you know it, the Green Sword of Destiny has been stolen and this cast of characters is embarked on an adventure replete with the requisite chases, duels, romance, and big operatic moments.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon has much to recommend it. The heart of the movie is its martial arts fight scenes, which were choreographed by Yuen Wo Ping, who also did the fight choreography for The Matrix. Watching these fights, in which dueling opponents move about one another, striking and parrying blows, with dizzying speed, offer a similar pleasure as watching acrobatics or carefully synchronized dancing.

The fight scenes are enhanced by the conceit, derived from Taoist tradition, that skilled warriors can defy physical laws, variously jumping impossible distances, walking on water, or outright flying. The actors and stunt people thus frequently move about on wires during the action scenes, like martial arts versions of Peter Pan.

How viewers react to this self-consciously unrealistic touch will probably have a big influence on their appreciation of the fight scenes. For my part, I was willing to accept the magical elements. The warriors’ gravity-defying abilities felt tonally consistent with the dance-like quality of the action choreography and at the very least looked no more silly (and far less digital) than displays of similar abilities by American superheroes.

The stand-out action set piece is a simultaneously exhilarating and exhausting show down at the martial arts school between Jen and Shu Lien (readers will remember I paid tribute to this scene in my Shang-Chi review).

Another good scene is a night-time duel between Shu Lien and a masked opponent. A shorter but still memorable set piece is a confrontation between Li and Jen amid the treetops of a forest, where they must contend not only with each other but with the ever-shifting nature of the terrain.

I note that both Shu Lien’s night-time fight and the Li and Jen fight also contain unexpectedly funny moments in which one of the duelists applies a simple, direct, and effective tactic. In such moments, the parallels between the fight scenes and old silent comedy also become apparent.

A different type of comedy pops up in a fast-paced sequence in which Jen must face off against an array of thugs; the over-the-top action here recalled Looney Tunes cartoons.

Beyond the action set-pieces, Lee and his cinematographer Peter Pau provide other beautiful sights in the movie. Crouching Tiger features some stunning natural beauty, ranging from the desolate landscapes of the Xinjiang region (including what seems to be the Asian equivalent of the Painted Desert) to a monastic retreat located atop lush, misty mountains. I also appreciated the use of color, from the vibrant green of the trees to the deep reds of a wedding procession.

The performances are good. I found Zhang Ziyi’s acting style a bit too broad in The Road Home, but her approach is well suited to the bold, passionate Jen. In contrast, Chow Yun Fat and especially Michelle Yeoh offer nice studies in underplaying, conveying a lot of emotion with relatively small gestures. I also appreciated Lung Sihung’s performance as Sir Te, the somewhat curmudgeonly but bemused aristocrat charged with caring for the Green Sword of Destiny.

The screenplay also provides its own intriguing study in contrasts among the characters by including two very different romantic couples. The older couple Li Mui Bai and Shu Lien care deeply for each other but their personal code prevents them from openly displaying or acting on their feelings. The younger Jen, however, acts on her feelings and engages in an intense romance in defiance of social convention with Lo, a “barbarian” from Xinjiang (is Lo meant to be a Uighur, I wonder?).

We get a sense of Jen and Lo’s romance from an extended flashback in the middle of the movie about their initial meet cute. Lo was a bandit chieftain who raided Jen’s caravan and stole her beloved comb. She pursues him into the wilderness and repeatedly fights him to get her property back. In the process, they fall in love. It’s all rather like It Happened One Night, but with more hand-to-hand combat.

The movie thus gives us two complementary romances: one older and repressed, one younger and open. Which relationship will ultimately prove the stronger, though?

(For my part, I have to say that for all the passion of Jen and Lo’s relationship, they cannot hold a candle to Li Mui Bai and Shu Lien. Just watch the lovely scene where those two share some tea and talk about how special it is just to quietly be together; it does not get more romantic than that.)

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon has many strengths. Yet the movie also has a glaring weakness, at least as far as I was concerned.

For all the excitement of the fight scenes, beauty of the imagery, and skill of the performances, I found the story pretty uninteresting. Compared to typical adventure stories, Crouching Tiger has remarkably low stakes. The heroes do not need to save the world, protect the kingdom from invasion, or even liberate a village from bandits.

All Jen cares about is the rather vague goal of being left alone to pursue her own path in life. Given her strong will and immense fighting skill, we are given little reason to doubt she can achieve her ambition. More to the point, few other characters seem particularly interested in thwarting this goal—Li and Shu Lien certainly are not—so her quest for independence generates little real conflict.

What conflict there is here revolves around possession of the Green Sword of Destiny. Since the sword’s significance seems largely symbolic, though, I found it hard to care too much about who ends up with it. Granted, the movie also contains the subplot about the search for the Jade Fox, but that takes up relatively little screen-time and Li, despite his ostensible personal stake in the chase, does not seem that interested in it for much of the movie.

Because of the story’s lackluster quality, the ultimately tragic conclusion does not have much emotional impact. I could not help thinking that a better, less costly resolution could have been easily achieved.

In Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Lee and his team created what I would describe as a beautiful-looking, skillfully made, but rather hollow movie. Still, I am glad to have been introduced to the wuxia genre by it. As I continue my retrospective, I will be interested in seeing what Zhang Yimou did with the genre.

Leave a comment