I continue to catch up, over the holidays, on interesting content. Moving outside my usual reviewing scope, I look at a book and a miniseries. They are both about the movies, though, so it is not that big a change!

Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War (2014), by Mark Harris, is a fascinating book about five great filmmakers and an important era in the American movie industry as a whole. Like any successful property, the book inevitably inspired its own screen adaptation, a Netflix documentary series of the same name that involved its own crew of film notables. Having read the book and watched the series, I will provide my assessments of both.

Five Came Back is about the careers of Hollywood directors William Wyler, John Ford, Frank Capra, John Huston, and George Stevens. The book specifically examines each man’s career during the Second World War, when each one made movies for the US military in an attempt to further the American war effort.

Wyler portrayed Britain’s wartime struggles in the fictional Mrs. Miniver (1942) and later recorded Allied bombing runs over Germany in the documentary The Memphis Belle: The Story of a Flying Fortress (1944). Ford shot footage of both the Battle of Midway and the Normandy invasion. Back in the States, Capra oversaw a series of propaganda and educational films for recruits, most famously the Why We Fight series. Huston witnessed fighting in the Aleutians and Italy and produced films from those experiences. Stevens followed the victorious Allied armies into France and Germany and recorded the horrors of Nazi Germany’s concentration camps. Through these five men’s often harrowing experiences, Five Came Back provides a window into the larger role American moviemaking played in World War II.

Five Came Back also provides a sketch of each director’s background and personality. Wyler was a methodical director of dramas (including several Bette Davis vehicles) and, as a Jewish immigrant from Alsace, had a personal interest in the war against Hitler. The crusty, hard-drinking Ford was infatuated with the kind of male heroism and camaraderie captured in his westerns. The Sicilian-born Capra advocated patriotism and an uncertain populism. Huston was highly gifted but equally dissolute and unpredictable. The withdrawn Stevens was best known for light comedies and seemed an unlikely man to record the war, let alone its most terrible aspects.

The greatest strength of Harris’ book is simultaneously its greatest weakness: the sheer breadth of the material covered. Each director’s career, as well as Hollywood’s role in World War II, could be (and has been) the topic of its own book; combining all these topics into the same volume was an especially ambitious undertaking.

Whether the book is recounting the pre-Pearl Harbor debates within the United States, including within the movie industry, about whether to enter the war; Capra’s efforts to coordinate propaganda movies; Ford filming at Midway; Wyler flying with bomber crews; Huston’s travails in war-torn Italy; or Stevens’ journey through newly liberated Europe, the sheer number of events and subjects included in Five Came Back ensures that some interesting episode or bit of information turns up on almost every page. The abundance of material, combined with Harris’ clear, non-academic prose and skillful way of hopping back and forth among the five principals’ stories, makes the 400+-page book a gripping and surprisingly quick read.

From this sprawling narrative, two main themes emerge. One is the conflict among the triple imperatives of accurately representing the war, carrying out official government policy, and making entertaining (and profitable) movies. The unsurprising pattern was that accuracy generally took the lowest priority during the war years.

Early on in the production of the Why We Fight series, Capra insisted on giving a simplified account of the war and its political context to military recruits: “You give him a lot of ‘On the other hand’s and you confuse him completely,” Capra declared. When editing his Midway film, Ford slipped in a close-up of James Roosevelt, the president’s son; whether the younger Roosevelt was present at the battle was unclear, but the shot guaranteed presidential support for the movie. Political considerations prevented Wyler from giving Memphis Belle the downbeat tone he desired. Government censorship suppressed Let There Be Light (1946), Huston’s post-war film on psychological trauma among veterans, for decades.

Harris also bluntly recounts how some of the directors engaged in unambiguous fabrication. Stevens filmed reenactments of Americans fighting in North Africa that was presented as authentic battle footage. Later, Huston did the same thing more artfully to create the supposed documentary The Battle of San Pietro (1945).

Most dismaying in its own way is the fact that roughly halfway through the war years, Hollywood became much less interested in the Allied war effort. The market had become over-saturated with war movies and the studios altered course to give the public what they wanted, even as the actual war continued to rage.

The other major theme of Five Came Back is how wartime service affected the five directors’ careers and personalities. Exposure to combat and the terrible loss of life from the war left Wyler, Ford, Huston, and Stevens all emotionally scarred in varying degrees; in Wyler’s case, the war also left him with significant hearing loss.

The war’s legacy, Harris argues, influenced the directors’ post-war moviemaking: Wyler explored disability and the difficulties of returning to civilian society in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Stevens gave up the comedies that defined his pre-war career and focused exclusively on drama, including the film adaptation of The Diary of Anne Frank (1959). Ford and Huston explored bravery, comradeship, and moral complexity in their later movies. In contrast, Capra, who fought exclusively bureaucratic battles during the war and saw little carnage first-hand, had trouble adapting to the post-war industry.

Harris’ case that Capra’s different wartime experiences caused his career to languish is a bit strained, though. Following the war, Capra made It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), which, while not especially successful on initial release, went on to become probably the most well-known and beloved of all the movies any of the five directors made.

While all this makes for a very entertaining book, the main drawback to Five Came Back’s extensive and varied subject matter is that Harris cannot linger too long on any specific part of the narrative. Such vivid episodes as Ford’s experiences at Midway or Normandy, Wyler’s flights aboard the Memphis Belle, and Stevens’ first-hand witness of Nazi atrocities seem like they could support longer, more detailed accounts than Harris provides. Also, while Harris makes no secret of the many falsifications and distortions of US wartime filmmaking, he spends little time analyzing or commenting upon this unsettling reality. Readers are left to draw their own conclusions, which is a reasonable but somewhat disappointing approach.

Five Came Back also touches only in passing on what seem like potentially fascinating topics related to the war and the movies. Prelude to War (1942), Capra’s first Why We Fight propaganda film, is described as drawing “rowdy approval” from army recruits, but the book does not say much more about the reaction the Why We Fight films elicited from the military personnel who were their primary audience. Did the films shape young American men’s perceptions of the war they were fighting? Is any information available on this point?

Other films produced under Capra’s supervision and that receive a few pages in the book invite further exploration. The Battle of Russia (1943), a Why We Fight installment dealing with the European war’s eastern front (and one of the more critically praised films in the series), was created using extensive footage provided by the United States’ then-ally, the Soviet Union. More details about that unusual collaboration would have been interesting.

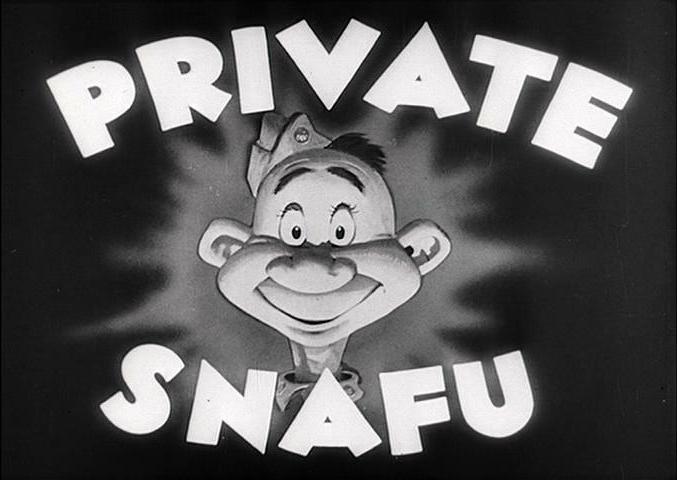

The book also contains a memorable but all-too-brief account of the “Private SNAFU” educational shorts, a raunchy animated series produced through a collaboration between Warner Brothers animator Chuck Jones and Theodore Geisel, aka, Dr. Seuss.

Another intriguing topic mentioned is the checkered history of race in World War II-era films. In general, the depiction of the Japanese in American wartime propaganda was notoriously racist. However, Five Came Back contains the notable detail that Lowell Mellett, an official in the Office of War Information, tried to curb the worst excesses of anti-Japanese sentiment in the movies—a significant example of government intervention actually making the portrayal of the war more nuanced. After Mellett lost his authority over US filmmaking, though, the movies leaned hard into hateful stereotypes. This melancholy tale would benefit from a fuller treatment.

The same is true of the fraught production of The Negro Soldier (1944), a government film meant to encourage Black Americans to join the armed forces. As described in Five Came Back, the film marked a notable step forward in some respects while remaining woefully constrained in others.*

I grant these complaints are somewhat unfair, as the topics I have mentioned are tangential to Harris’ focus on the five directors. I bring them up, though, just to illustrate how Five Came Back left me anxious to learn more about the topic. Perhaps that is in its own way a tribute to the book’s engrossing character: like any good entertainer, Harris leaves you wanting more.

And “more” was what we got. The book Five Came Back was followed by Five Came Back (2017), a documentary miniseries on Netflix directed by Laurent Bouzereau and written for the screen by Harris. The series tells the five directors’ stories over three episodes, each about hour.

Readers of the original source material will not encounter many surprises. On a purely informational level, the miniseries version of Five Came Back does not provide much beyond what is contained in the book. The events covered track pretty closely with the book’s narrative and are inevitably much abridged.

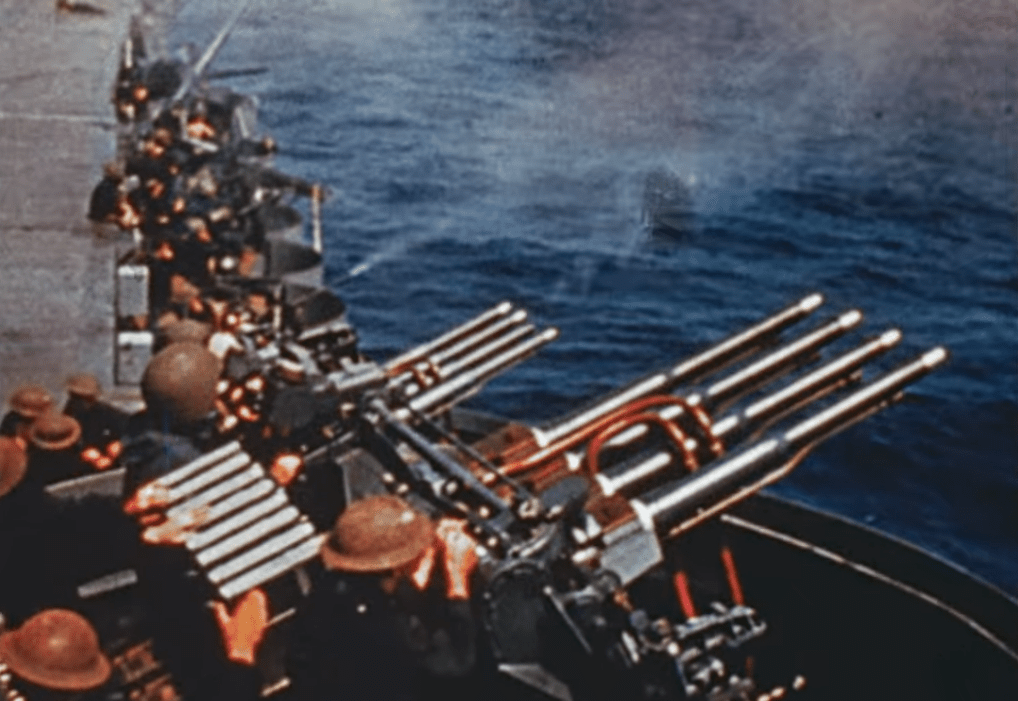

Two aspects of the miniseries elevate it beyond merely a Cliffs Notes counterpart to the book, though. One is inherent in the different medium: in a filmed series we are not limited to reading about the directors’ wartime experiences and movies; we can watch them play out on film, whether in newsreels, features, or more informal footage.

We watch what Ford captured at the Battle of Midway, the propaganda films Capra produced, what Wyler recorded in the bomber planes, and so on.** Seeing the directors’ wartime work, combined with clips from their peacetime movies and a wealth of other contemporary footage from the US war front and home front produces a more emotionally and imaginatively gripping experience than the book.

The series also includes plentiful film and audio clips from the many interviews all five directors gave over the course of their lives about their wartime work. We thus get a welcome sense of each man’s manner and personality: Wyler comes across as quietly good-humored; Ford is gruffly laconic; Capra, warmly expansive; Stevens is undemonstrative and slightly stolid; and Huston is the perpetually world-weary bon vivant (time spent listening to John Huston speak is always time well spent).

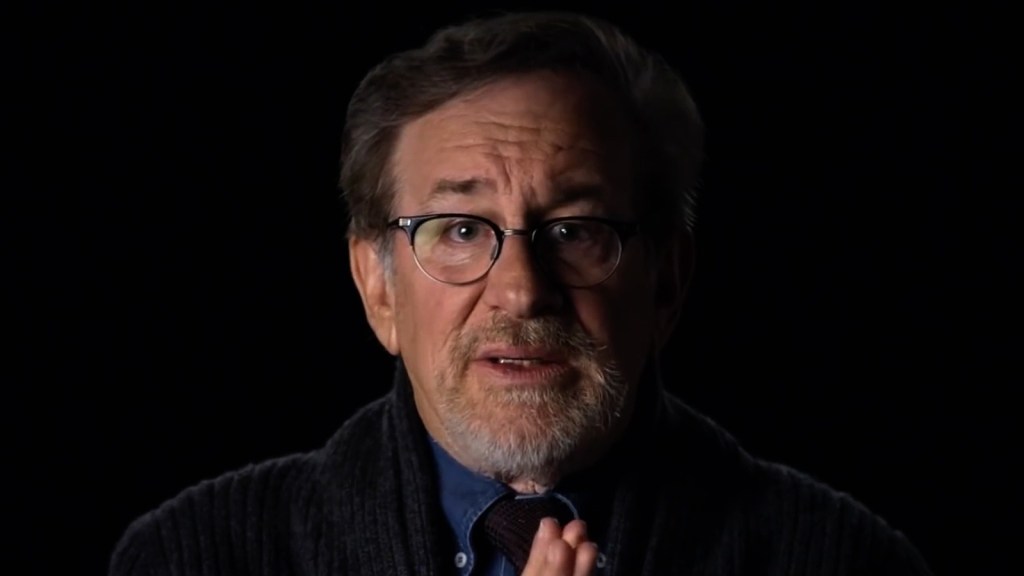

The other significant aspect of the Five Came Back documentary series is a clever storytelling device employed by Bouzereu and Harris. While the series has conventional voice-over narration, provided in quiet yet authoritative tones by Meryl Streep, the wartime careers of the five famous ‘40s-era directors are also recounted by, aptly enough, five famous contemporary directors. Steven Spielberg, Guillermo del Toro, Paul Greengrass, Francis Ford Coppola, and Lawrence Kasdan all take turns within the miniseries describing the experiences and work of their historical counterparts.

The five present-day directors occupy a somewhat uneasy position in the series, straddling the line between “co-narrators” and “interviewees.” The directors’ remarks are clearly scripted rather than being elicited by an off-camera interviewer: they speak directly into the camera, for example. The series’ creators also made the slightly disappointing choice of pairing each contemporary director with a specific past director, so Spielberg talks about Wyler; del Toro about Capra; Greengrass, Ford; Coppola, Huston; and Kasdan, Stevens. I suppose this structure was meant to keep clear which historical director was being discussed at any given moment, but I would have found it more interesting to mix up the commentary a bit.

What prevents the talking heads sequences with the contemporary directors from being merely a gimmick is that, as in the footage of the older generation of filmmakers, each director’s comments reflect his own distinctive style and sensibility. Spielberg is characteristically thoughtful, Greengrass has an engaging ebullience, Coppola speaks in his garrulous, expressive manner, and so on. The cumulative effect is rather like hearing a group of your favorite raconteur uncles telling you an epic story. The device adds a certain warmth to the miniseries that simple narration would not.

Sometimes the director-narrators inject more personal comments with no parallel in the original Harris book. Spielberg dwells on a riveting moment in Memphis Belle, where the camera follows the downward course of another bomber that has been shot down, and the impression this moment made on him. Both he and Coppola reflect on the faked battle footage in the Battle of San Pietro, with Coppola relating Huston’s filmmaking to his own experiences faking war in Apocalypse Now. Greengrass talks about how Ford’s rough, imperfect footage of Midway connects to his own struggles as a documentarian to convey events’ reality.

The Five Came Back series also addresses, in its own way, my dismay at the limited attention given in the book to animation and racial issues. The Private SNAFU series, anti-Japanese propaganda, and The Negro Soldier film all receive attention. While probably no more information on these topics is conveyed in the miniseries than in the book, the choice of including this material while excluding other information from the book means that these topics loom larger here. A clip from The Negro Soldier showing a mock sermon by the film’s screenwriter, Carlton Moss, is particularly striking.

I enjoyed both the book and miniseries versions of Five Came Back, yet I found they evoked differing (and revealing) reactions in me. When reading about Wyler, Capra, et al.’s wartime experiences in prose on a page, I was engaged but in a relatively analytical way. As noted above, the main impression the book left me with was the extreme difficulties of telling the truth about war amid the dueling pressures of wartime policy and the bottom line.

In contrast, seeing the five directors’ tales unfold on screen, through film footage that is by turns ominous (goose-stepping German troops, for example), wrenching (men killed in the Pacific or in concentration camps), or inspiring (ordinary people celebrating liberation by the Allies) and is all skillfully edited together and scored to music produced a radically different effect. I felt strongly moved by the series, which elicited a more cathartic reaction than the book.

These different responses could be said to sum up the essential differences between print and film. That film can grab us emotionally and sweep aside the more thoughtful, questioning side of our minds is a big part of what makes the medium so powerful and dangerous. This capacity of the movies also explains why the US government, in wartime, turned to these five men in the first place.

*If the poor portrayal of the Japanese or Black Americans receives minimal treatment in Five Came Back, another important topic that is almost entirely neglected is propaganda’s role in stirring up anti-German feelings.

The one notable exception is an unsettling story about the making of Mrs. Miniver. In the movie, Mrs. Miniver encounters a German pilot who has been shot down over Britain and attempts to take our heroine hostage in her own kitchen. Wyler insisted, over the objections of MGM head Louis B. Mayer, on portraying the pilot in the most negative way possible. As the director recalled, he wanted to present the German as “one of Goering’s monsters.” In the final movie, the pilot accordingly boasts about bombing civilians in the Dutch city of Rotterdam.

Harris does not comment on the scene’s larger significance, but the demonization of the only German character to appear in the movie is disturbing. The scene acquires a further bitter undertone when one considers that the Allies would go on to bomb German civilians in cities such as Hamburg and Dresden on a scale that dwarfed the Rotterdam bombing.

**A nice supplement to the Five Came Back miniseries is several of the five directors’ wartime movies, which Netflix has also made available: The Battle of Midway, Memphis Belle, multiple installments of the Why We Fight series, and more. As historical, political, and artistic pieces, these would make for fascinating viewing, and I may cover one or more of them in future posts.