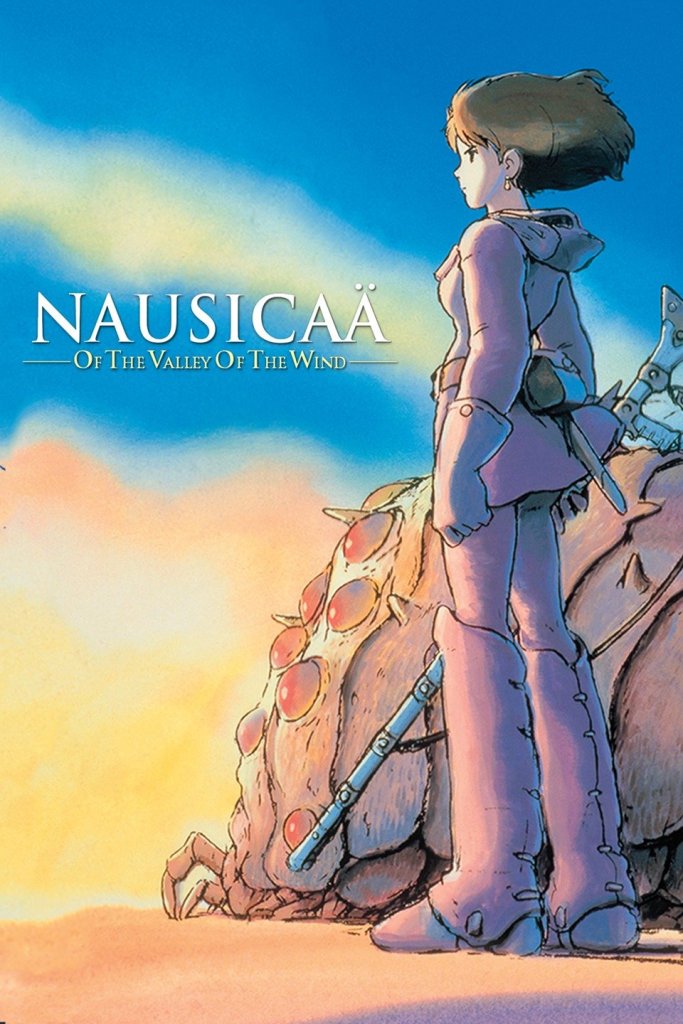

In the final review of my Ghibli retrospective, I examine the “proto-Ghibli” movie, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind.

Once upon a time, in the bygone era known as the early 1980s, a 40-something Japanese film director and artist named Hayao Miyazaki decided to make a movie.

Miyazaki had at the time directed some TV series and one previous feature film, an entry in the Lupin III comedy-adventure series. His new movie would be a science fiction adventure story adapted from a manga (comic book) he had created. The producer would be Miyazaki’s friend, another film director named Isao Takahata.

The pair did not have a studio of their own to make the movie, however. They therefore turned to the animation house Top Craft, which already had a significant body of work to its credit. Most notably (at least for a generation of American kids), Top Craft had done the animation for the Rankin/Bass adaptations of The Hobbit, Flight of Dragons, and The Last Unicorn.

Together, Miyazaki, Takahata, and the Top Craft animators made Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). This movie would be the proto-Studio Ghibli feature, both because its production brought together many people who would work together on the Ghibli movies (Joe Hisaishi also did the music) and because the movie contains story elements and themes that would become familiar parts of the Ghibli canon. The movie is typically included in lists of Ghibli movies, even though technically it was made before the studio’s founding.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which Miyazaki wrote as well as directed, takes place in a far distant future, centuries after human industrial civilization has collapsed in some shadowy cataclysm. The remnants of humanity have organized themselves into various scattered communities.

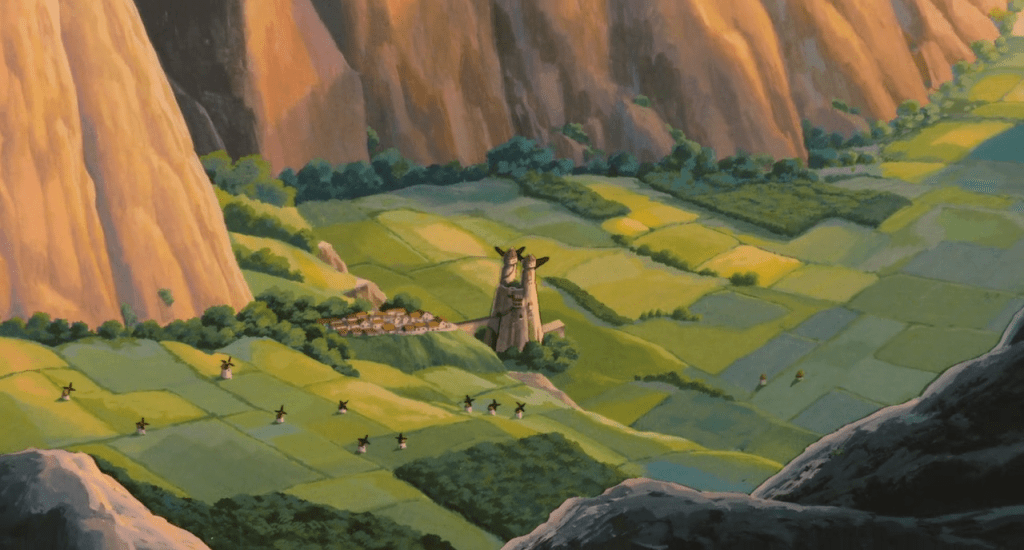

One such community lives in a lush green valley, relying on farming and wind power. They are ruled by the benevolent but ailing King Jihl and live a relatively peaceful and harmonious life.

The kingdom must contend with various dangers, however. Some come from other, more aggressive human societies. The primary danger, though, is the gradual encroachment of the Toxic Jungle, a massive, rainforest-like ecosystem spawned by past apocalyptic events.

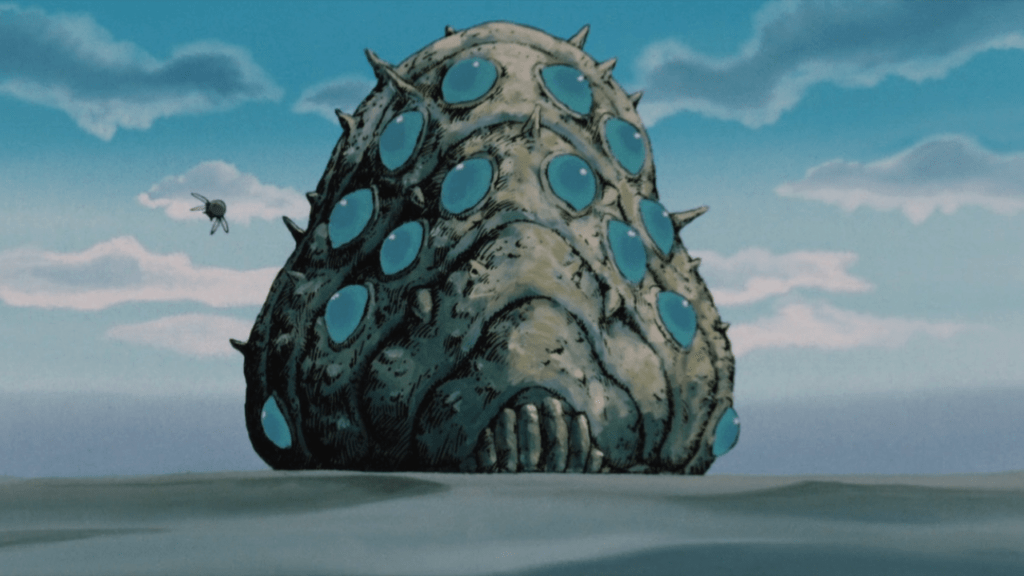

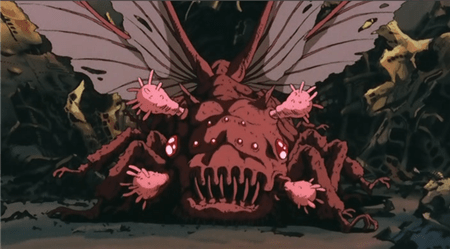

The Jungle’s plants and their spores are poisonous to humans and most other forms of animal and plant life. The only beings immune to the Jungle’s lethal effects are the array of mutated insects that inhabit it. Chief among these are the Ohm, gigantic creatures that resemble a cross between tarantulas and hermit crabs.

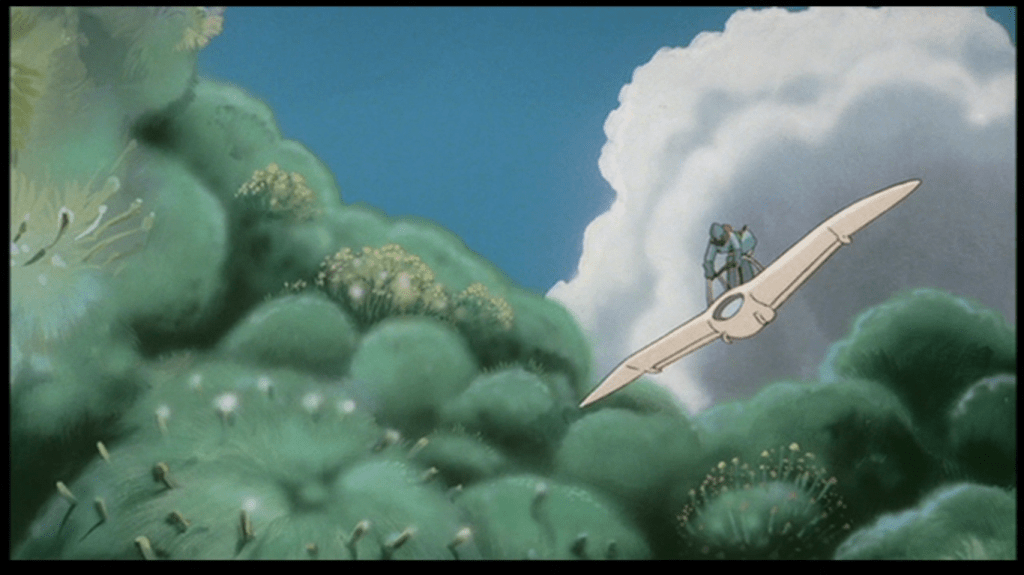

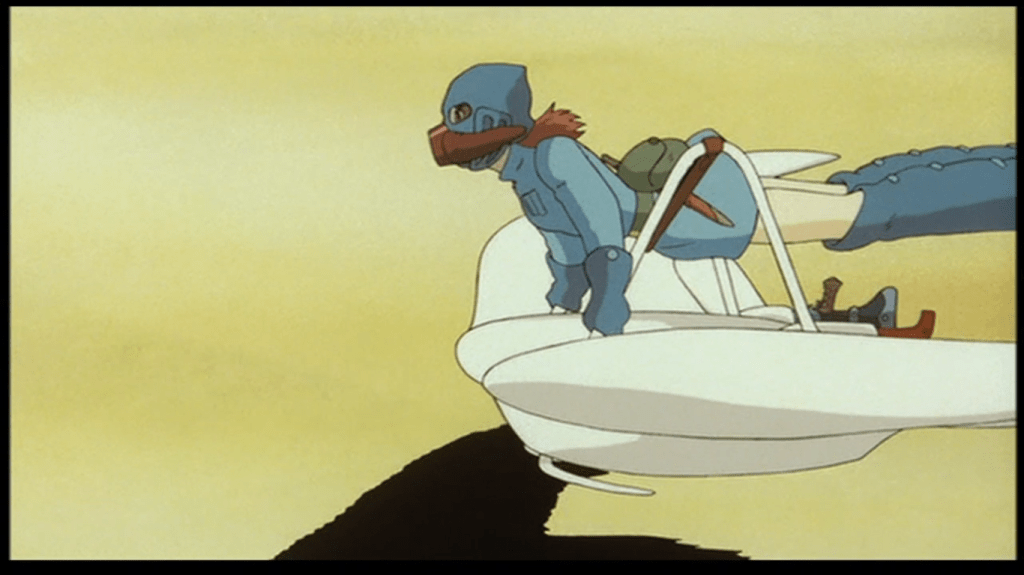

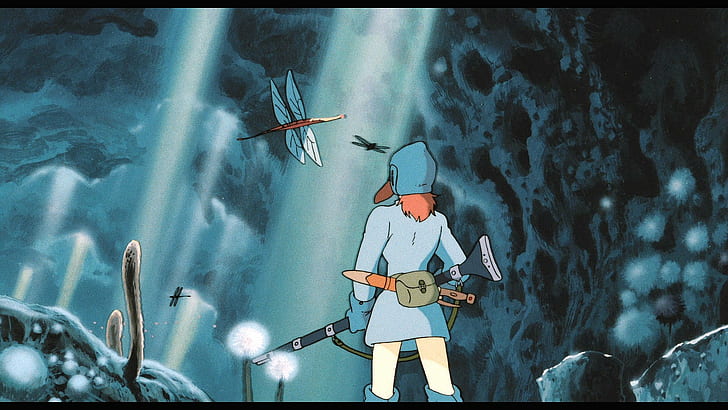

One human who is not afraid of the Jungle, the Ohm, or their associated dangers is King Jihl’s daughter, Princess Nausicaä. An explorer and naturalist, Nausicaä scouts the regions around her valley by means of a rocket-powered glider that she flies with ease. She will even venture into the Toxic Jungle. We see her do just this in the opening scenes, which in short order tell us everything we need to know about her.

Aided by a gas mask and other protective gear, Nausicaä walks through the Jungle and comes upon the carcass of a dead Ohm. Realizing that her people can use the Ohm’s body parts for various purposes, she removes one of its compound eyes, using gunpowder to blast through the Ohm’s armor-like exterior.

As she works, the trees release a shower of spores. Being protected from the spores’ lethal effects, Nausicaä pauses to contemplate their snowfall-like beauty. She is soon off again on her glider, though, carrying the deceased Ohm’s eye, which resembles an enormous circular window.

Outside the Jungle, she encounters Lord Yupa, an elder of her kingdom, being pursued by an enraged Ohm. Nausicaä flies between Yupa and the Ohm and manages to calm the creature and coax it into returning to the Jungle.

Yupa thanks her for saving him and introduces her to a new animal he has discovered in his own travels: a striped yellow mammal he calls a “fox squirrel” (I would describe it as more of a cat/hyena hybrid, but that’s just me). The animal is initially hostile, biting Nausicaä’s finger when she reaches out. She remains calm, however, and soon the fox squirrel warms to her. It becomes her pet, spending the rest of the movie following her around.

This, then, is our heroine: brave, smart, endlessly curious about flora and fauna, and preferring to communicate with dangerous animals rather than harm them. Having quickly established Nausicaä as a character, the movie wastes little time before putting her strengths to the test.

Soon a warlike society known as the Tolmekians have invaded Nausicaä’s valley kingdom. Their aim is not merely conquest, though. Led by Kushana, a steely female warrior-aristocrat, the Tolmekians are on a mission to reassert human control over the planet by wiping out the Ohm and destroying the Toxic Jungle. To this end, they are reviving a long-dormant super-weapon from humanity’s past.

Nausicaä shortly finds herself on a quest to protect her people while making peace between the Tolmekians and another human community as well as between humanity and the natural world. On this mission, she will travel far, across the Jungle and other surrounding regions, and face many dangers.

After its strong protagonist, the chief appeal of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is of course the animation: specifically, the movie’s futuristic world-building and various action sequences. In keeping with its early 1980s production, the artwork is less polished and more broadly “cartoonish” than recent anime, but that does not dim the creativity and energy on display.

Part of the fun is the sheer variety of physical environments. A setting such as the Toxic Jungle would be enough to sustain a movie, but Miyazaki and the Top Craft animators are not content with that.

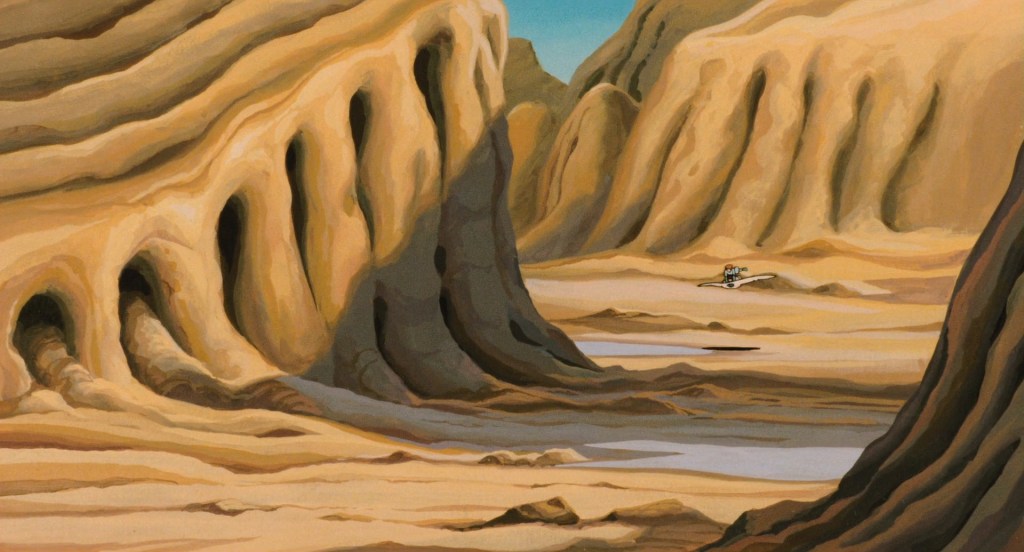

The action constantly shifts from one distinct place to another, whether it is the Jungle’s dark, tangled interior; the bucolic Valley of the Wind, with its orchards, crop rows, and windmills; a desert spotted with wreckage and Ozymandias-like statuary; or an eerily peaceful petrified forest in which Nausicaä briefly finds refuge. Although the story’s fast pace prevents the movie from spending too much time in any of these locations, the filmmakers give each of them a sense of history: they feel like places where other stories have occurred or could occur.

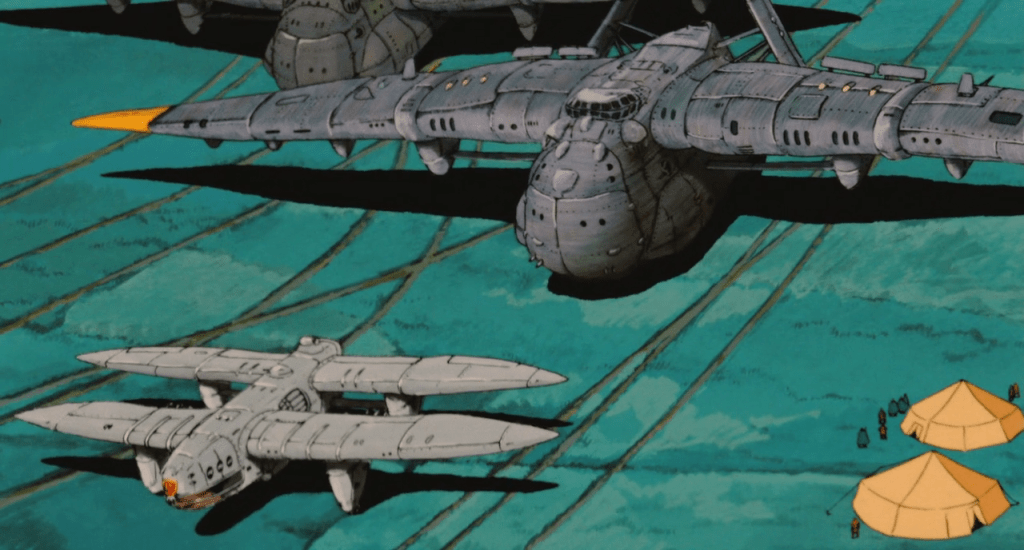

The human communities in the movie have an eclectic look that is appropriate for this post-apocalyptic world. People’s clothes and the castle where Nausicaä and King Jihl live seem vaguely medieval, but characters fight with firearms and tanks and fly in aircraft.

Nausicaä also includes some nice character design. Among the human characters, I appreciated how Lord Yupa and other older men in the Valley sport walrus mustaches that cover the entire lower halves of their faces.

The villainous Kushana wears a long cloak that we eventually learn conceals some unexpected characteristics. A subtle but striking aspect of Nausicaä’s appearance is how, in contrast to most of the other characters, her eyes are not plain black circles but have brownish-red irises that contain flaws. This gives her eyes a faint “starburst” quality.

The real triumphs of character design, though, are not with the humans but with the various non-human inhabitants of the Toxic Jungle. In addition to the colossal Ohm, the Jungle houses many animals that resemble real-life insects, arachnids, or crustaceans, but with the grotesquerie pushed to the extreme. Mandibles, wings, and red eyes abound—this is probably not the movie to show people with insect phobias. (Although the most terrifying creature in the movie is a very different kind of being who makes an appearance in the final act.)

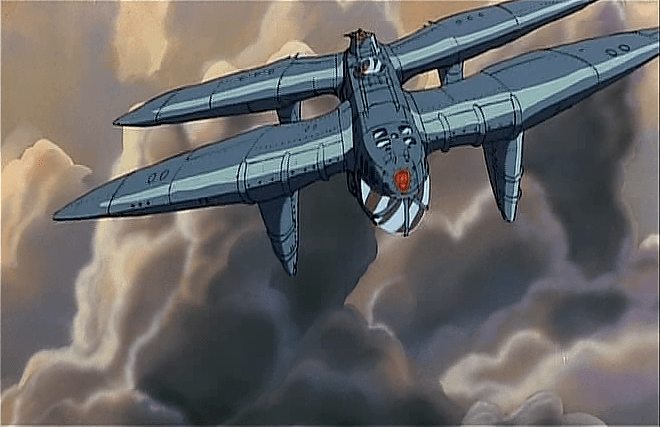

The existence of aircraft in this future world means that we get numerous scenes of flight, including chases and dogfights. Flight has always been Miyazaki’s passion, and the aerial scenes are rendered with the skill that would become his specialty.

The planes are drawn with appropriate mechanical grandeur or menace, and the animation sweeps along with them, with shifting perspective creating the illusion of movement through three-dimensional space. A sequence involving one plane attacking and then trying to board another is particularly good, with the vehicles involved and the nature of the action continually changing.

Complementing the airborne action sequences are more grounded ones. We get two well-choreographed scenes of hand-to-hand combat, in each of which an unexpected character displays unusual fighting prowess. The movie’s climax revolves around a larger-scale sequence involving a great convergence of opposing forces in the desert.

As all these battles and fights might suggest, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is an unusually violent entry in Miyazaki’s body of work. I am not sure of the total body count, but it is astonishingly high. The movie is mostly free of blood or gore (one of the more piercing moments is when a character’s injuries are not directly shown but we see Nausicaä reacting to them). But the frequent deaths of characters, combined with the many frightening creatures, make this one of Miyazaki’s darker, less kid-appropriate movies.

World-building and action aside, the movie also contains many images that are beautiful or haunting in isolation. Certain visual motifs turn up repeatedly: one that recurs during the aerial scenes is the image of a human figure briefly but clearly glimpsed amid flight. Another is the use of pinpoints of light in the distance to announce the presence of something large and powerful. Yet another is how intense light from fire, explosives, or the like will temporarily make the on-screen images go monochromatic. A particularly powerful shot, which combines elements of these motifs, is when an all-too-familiar sight fills the night-time sky.

Overall, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is a very well-made, visually impressive science fiction action movie. If I have any criticism, it would be the relatively minor one that the movie lacks emotional depth.

While Nausicaä is definitely a great heroine, the large cast and packed plot means that the supporting characters are not very well developed and consequently neither are Nausicaä’s relationships with any of them. For example, Lord Yupa seems to be a mentor figure to Nausicaä. Asbell, an angry young man she encounters in her travels, seems like a possible friend or even love interest. She never spends enough time with either of them, however, for much to come of these relationships.

Further, although the movie is clearly trying to saying something weighty about respecting nature and seeking understanding rather than resorting to violence, these themes are not handled well. As I noted above, this is a pretty violent movie, in which most characters, including Nausicaä, use force in certain situations. Declarations about the importance of nonviolence ring a bit hollow in this context. When one character does make a crucial choice to pursue nonviolence, it comes across as too pat, since the plot mechanics essentially allow both the character and movie to have their cake and eat it, too. Still, these are quibbles; for the most part, Nausicaä is an effective adventure movie.

In the English dub, Alison Lohman does a good job as Nausicaä, turning in an appropriately earnest, passionate vocal performance. Among the supporting voice cast, two actors stand out. As Lord Yupa, Patrick Stewart fills out the underwritten role with all his customary gravitas and warmth. As Kurotawa, Kushana’s weaselly assistant, Chris Sarandon has an ironic delivery that brings both a self-awareness and self-amusement to Kurotawa’s villainy.

My choice for favorite image in the movie is of Nausicaä standing up in the cockpit of a plane as it makes a low-level night-time flight across the desert. As she flies, the princess is framed by the darkened sky and a sea of red lights in the distance. The image is both a hero shot and also quietly eerie.

My choice for favorite humanizing detail in the movie is perhaps the platonic ideal of such an element. During one dramatic scene, several characters are engaged in conversation when a young boy bursts into the room to deliver important news. As he begins to do so, though, another young boy, who has been guarding the door, interrupts and demands that the new arrival provide the required password. The messenger boy breathlessly gives the password and then proceeds to share his news. Such a small yet unexpected (and funny) pause in the middle of otherwise intense proceedings made me laugh out loud.

Despite their admirable work on Nausicaä, Top Craft sadly did not prosper. The studio would break up shortly after the movie’s release. Miyazaki and Takahata did continue their filmmaking, though. In 1985, together with producer Toshio Suzuki, they founded a new studio which also included some former Top Craft animators.

Having a studio of their own gave the filmmakers an opportunity to tell new stories that, like Nausicaä, involved strong female protagonists, fantastical settings, ecological themes, flying machines, and, of course, amazing imagery. After that, the sky was the limit.

Leave a comment