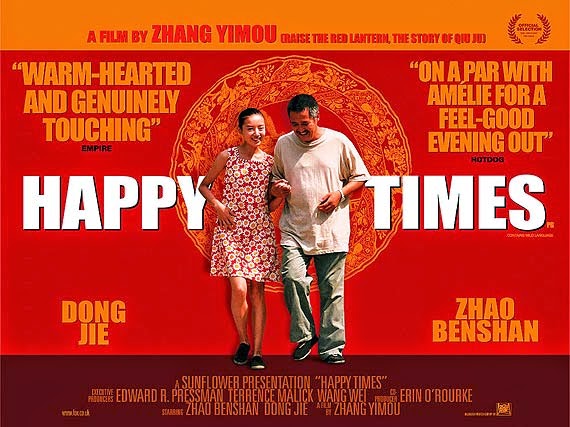

Next in my Zhang Yimou retrospective, I review the off-beat Happy Times.

Happy Times (2000) is a movie that should not work. The plot is strange and wildly implausible. The tone occupies an uneasy middle ground somewhere between the comic and the tragic, the sappy and the bleak. The conclusion seems likely to leave many viewers dissatisfied.

Yet, in spite of all that, the movie works. Or at least it did for me. Happy Times owes its improbable success to the filmmakers’ delicate handling of the story and effective performances by its two leads.

Directed by Zhang Yimou and written by Gai Zi (from a novel by Mo Yan), Happy Times follows the complicated life of Zhao (Zhao Benshan), an older man who is looking to get married. Zhao is not exactly the most appealing catch, though: he has no job and limited income and generally gets along by borrowing money from others.

As the movie opens, Zhao has persuaded a woman (Dong Lifan) to get engaged to him by deceiving her into thinking he is a successful entrepreneur.

Helped by his younger friend Fu (Fu Biao), Zhao tries to raise money for the wedding through a half-baked business scheme. They refurbish an abandoned bus into a makeshift apartment—dubbed the “Happy Times Hut”—in the middle of a public park. Zhao and Fu figure they can rent the place to couples looking for an impromptu location for trysts. This scheme does not quite go according to plan.

Meanwhile, as Zhao gets to know his fiancée, he meets two other members of her household. One is her spoiled young son (Leng Qibin) and the other is her adolescent stepdaughter Wu Ying (Dong Jie). Wu Ying is blind, having lost her vision earlier in life. We quickly gather that she is not liked or treated well by her stepmother and stepbrother. Trapped in an unhappy situation, the young woman cherishes the hope that her father will come back some day, ideally with enough money for surgery to give her eyesight again.

The fiancée sees an opportunity in her new romantic relationship. Since Zhao is such a successful businessman who runs a hotel or something, why doesn’t he get her stepdaughter a job? That will get her out of the house and stop her from being a burden. Soon Zhao’s marital hopes depend on looking after his new charge.

Given the broad outlines of this story—circumstances force a scoundrel to care for a vulnerable young person—you might well guess at what happens in Happy Times. You would be roughly correct, but the movie does not quite unfold as expected.

A story like this is a tricky mixture of the farcical (elaborate deceptions, embarrassing situations, comical mishaps) and the serious (poverty, broken families, the abuse of people with disabilities). Zhang and his team are generally able to finesse this combination of elements through cinematic understatement. They do not try too hard either to make us laugh during the more comical passages or to wring tears from us over the more painful aspects of the plot.

Both Gai’s screenplay and Zhang’s direction contribute to this restraint. Scenes that in other writers’ hands might build to some absurd, over-the-top climax play out to a more modest conclusion here. Zhao and Fu’s Happy Times Hut scheme, for example, fizzles over Zhao’s discomfort with the seedy concept. When a couple visits the Hut, no bawdy, compromising situations ensue: Zhao just insists that they leave the doors of the establishment open at all times and the couple eventually leaves in irritation. Scenes in which Zhao has to evade Wu’s detection by keeping quiet and staying out of her way similarly do not involve any pratfalls or crashing into furniture, just some awkward moments.

Zhang’s penchant for a quasi-cinema vérité style also contributes to the restrained approach. An elaborate scheme by Zhao and his friends to deceive Wu is presented almost like a documentary, with few musical cues or big reaction shots to underline the comedy. Later, a lunchtime conversation among Zhao, Wu, and Fu conveys information that viewed objectively is emotionally devastating. Yet the scene unfolds in a single unbroken long shot, which takes much of the sting out of the revelations.

The result is a movie that does not inspire laughs or tears so much as moderate amusement and equally moderate melancholy. This middling approach keeps the unstable mixture of comedy and tragedy from splitting the movie apart.

Some moments are particularly striking. I appreciated a scene where Zhao takes Wu to the Happy Times Hut to begin work there only to discover that the bus-turned-apartment is being hauled away by some city workmen. Zhao then improvises for Wu’s benefit, pretending to direct the men in their “renovations” of the site, to the workmen’s perplexity.

I was also moved by a scene set at the fiancée’s apartment. Her son is eating a container of ice cream, and Zhao gently suggests his stepsister might like some as well. The boy dismisses the idea, but his mother responds by giving Wu her own container of ice cream. Shortly thereafter, Zhao says goodnight and leaves. The moment he is out the door, the fiancée snatches the ice cream away from Wu.

The central relationship between Zhao and Wu is handled with the same restraint as the rest of the movie. Although Zhao inevitably comes to care for the young woman under his care, his change of heart is kept relatively undramatic. He does not start out too bad or turn too good later. Zhao begins the movie as a dishonest deadbeat, but he is not a malicious or mean-spirited man. Later, his concern for Wu is still leavened by a certain selfishness. In a late scene that parallels the earlier incident at the fiancée’s apartment, Zhao agrees to treat Wu to some ice cream from a street vendor. When he discovers how much an ice cream costs, though, he just buys her a popsicle, lying that the vendor was out of ice cream.

As the two main characters, Zhao Benshan and Dong Jie must carry this movie, and both do excellent work. Their acting choices nicely balance each other. Zhao gives an energetic performance, in keeping with his desperate, fast-talking character. In contrast, Dong emphasizes Wu Ying’s self-contained, reticent nature. She conveys little overt emotion, which makes her rare displays of it—her tears over her home life, her evident pleasure in getting dressed up for a new job—land more powerfully. Dong also portrays the character’s blindness persuasively enough that I was slightly surprised to learn the actress is not blind in real life.

In certain respects, Happy Times reminds me of various older Hollywood movies. The most obvious similarity is with Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights, another sad-but-funny story that revolves around a down-on-his-luck protagonist trying to deceive a young blind woman. I also detected a whiff of Billy Wilder’s work here; Wilder specialized in combining dark and comedic material in a way that (depending on the movie or the viewer’s tastes) came across as either clever or off-putting. The “Happy Times Hut” scheme, for example, is a device straight out of Wilder’s The Apartment. Also, Zhao Benshan recalls frequent Wilder leading man Jack Lemmon; both actors share a lovable-loser quality.

The most surprising, even jarring, part of Happy Times is its ending. Indeed, the ending was apparently so controversial that Zhang used a different ending for the version of the film shown within China. The version I saw was strictly for the international release. Without giving too much away, suffice it say that Zhang employs one of his favorite tricks, the Tragic Reversal, to bring the story to a “resolution” that does not really resolve that much.

I am not sure how I would feel on repeated viewings, but at first viewing I liked this ending. The movie does not have a conventionally happy conclusion but does end on a (perhaps quixotically) hopeful note. That seems an appropriate final tone for this unusual story. I also appreciated how the movie avoided the kind of confrontation that in a more predictable movie might have figured prominently in the later scenes. Above all, the ending gets the most important element right: both Zhao and Wu ultimately change, ending the movie in subtly but significantly different emotional places from where they began.

Happy Times was the fourth in a string of relatively low-key, contemporary movies that Zhang made in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Following this movie, though, his film-making would take another new turn.

Leave a comment