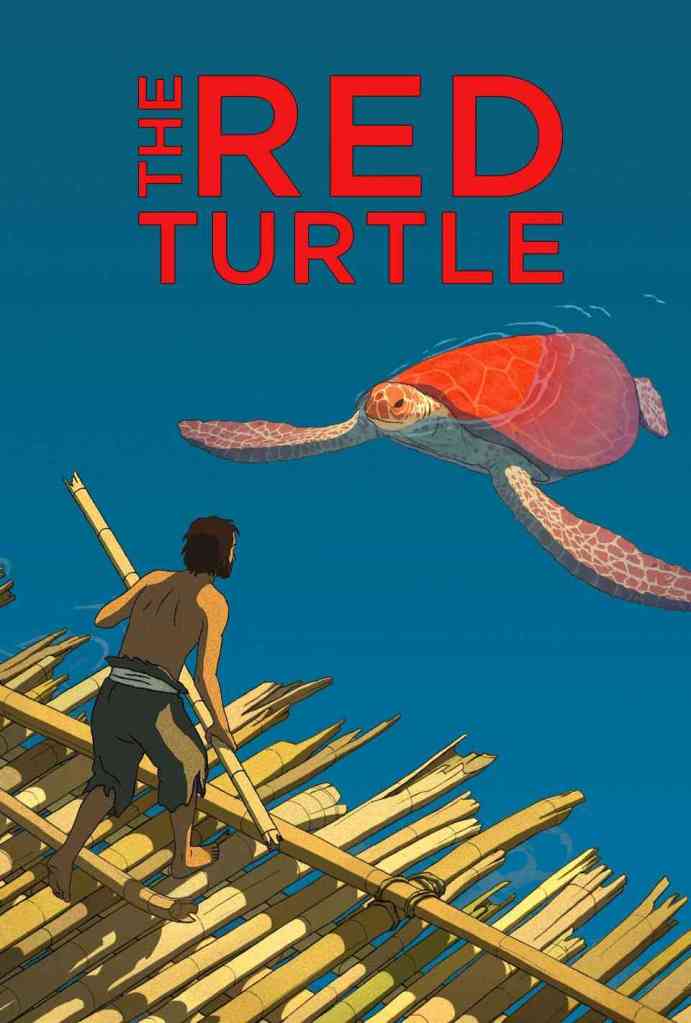

Next in my Studio Ghibli retrospective, I look at The Red Turtle.

Probably the first point to address in reviewing The Red Turtle (2016) is “Does this really count as a Ghibli movie?”

My answer: Yes, to me it counts. The movie was co-produced by Studio Ghibli and as such is part of the studio’s body of work, even if it followed a very different production path than most other Ghibli movies. (For more on the movie’s production history, see the post-script at the end of this review.)

The Red Turtle was directed by Michael Dudok de Wit, a Dutch animator who also co-wrote the screenplay with Pascale Ferran. The animation was overseen by French company Prima Linea. This filmmaking team created a movie that is conceptually daring and visually dazzling but somewhat cold.

The movie’s story, which is told entirely without dialogue (save a few half-articulated cries here and there) is about a man shipwrecked on a desert island. He spends his days living off the available plants and animals and trying to build a raft to escape the island.

The man’s attempts to sail away are repeatedly thwarted, however, by some mysterious creature that is soon revealed to be an enormous red sea turtle. He initially regards the turtle with understandable hostility, yet there is more to this turtle than meets the eye. The man discovers an unexpected aspect of the red turtle that dramatically transforms his life and his relationship to the island.

The plot, such as it is, is not really the point of The Red Turtle, though. The point is how de Wit and his team animate the island and surrounding sea, which they render with extraordinary beauty.

Consistent with the film’s production by a non-Ghibli, non-Japanese team, the animation style is completely different from any other Ghibli movie and does not look like standard anime.

Most of the draftsmanship is relatively spare, relying on clear, strong strokes to present the characters and setting. The style reminded me of the work of another noted Low Countries artist, the great Belgian cartoonist Herge, creator of the Tintin comics.

Sometimes, though, the filmmakers depart from the minimalist style to go for a more impressionistic effect. The island’s vegetation, especially a dense bamboo forest, is drawn as a fuzzy profusion of little lines and squiggles that make the surroundings feel engulfing.

The ocean is similarly drawn with watercolor-like blotches that add texture.

Using these visual approaches, de Wit and his team create one stunning image after another: after a certain point, I lost track of how many shots could easily serve as stand-alone paintings.

They are helped by their subject matter, which provides the occasion for two of the most reliably striking kinds of imagery: the natural world in all its variety (forest, rocks, beach, sea); and a small human figure framed against some vast expanse of land, sea, or sky. In dusk scenes, sunlight is used especially well. I also appreciated the visual flourish of rendering night-time scenes in black-and-white.

Beyond the Red Turtle’s sheer beauty, I liked a few other touches in how the filmmakers told their story. In an underwater scene, the relative skills of two swimmers are made clear by the speed with which one moves versus the slower, clumsier movements of the other. The contrast of sound and silence is used effectively, as in two powerful moments when a sudden halt of background noise signals a dramatic turn of events.

The movie also includes a welcome sense of gravity and danger. While the island and surrounding ocean may look gorgeous, the viewer is never allowed to forget how precarious life in this environment is. Characters are often faced with perilous situations; a mercifully brief sequence involving a flooded underwater cave had me gasping for breath.

Meanwhile, the dead bodies of various sea creatures—fish, crabs, a sea lion—are a regular feature of the island’s shoreline. Both dead and living creatures end up as prey for other island inhabitants. The constant presence of flocks of gulls and scavenging hermit crabs serve as zoological reminders that at any moment the protagonist or other characters might become someone’s else meal. A brief vignette involving a crab initially threatens to veer into cutesiness before taking a macabre twist—a sign of how unsentimental de Wit and his team can be.

All these elements serve the movie well. The movie is less well-served by its story, which I found rather uninvolving. With its dialogue-free screenplay, nameless characters, non-specific time and place, gestures toward common human experiences, and echoes of earlier stories such as those of Urashima Taro and the Bible, The Red Turtle is clearly trying to achieve a fable-like quality. I do not think it quite succeeds, though. Aside from a few powerful moments, this tale of the shipwrecked man and his island encounters did not strike a chord in my imagination, as fables and myths should.

Perhaps the problem is just that even The Red Turtle’s modest 80 minutes is a bit too long for a story like this. De Wit’s previous animated works tended to be around 5 minutes, and I think something closer to that would have worked better here. I can imagine The Red Turtle being brilliant as 15-minute segment in Fantasia. As it is, the movie feels too drawn out to have the simple power of a fable but too impersonal to work as a conventional drama.

Picking a favorite image from a movie that is essentially a montage of great images is challenging. Since I have set myself the task in this retrospective series, though, I would select two images as stand-outs. One is a shot of the man in the island’s bamboo forest at night, seemingly lost in its depths. The other is a shot of gulls flying over the ocean, in which the birds and clouds, sky and water, all blur together in a kind of glorious haze.

As for a favorite humanizing detail, I am going to pick a more general characteristic than I typically do. I like how de Wit and his animators use character’s shadows in this movie. For all their consummate skill, I do not recall Ghibli animators using shadows much—indeed, in one scene of My Neighbor Totoro, they notoriously neglected to draw shadows for the two main characters.

The Red Turtle is different. The filmmakers include characters’ shadows in scenes set both on land and in the water, realistically varying the shadows’ length in accord with the time of day, and sometimes using shadows for dramatic effect. In one scene, a shadow’s appearance announces a character’s presence before the character appears; in another, the movement of shadows emphasizes a change in two characters’ relationship. Like the numerous gratuitous details the Ghibli animators put into their work, the presence and use of shadows here adds to the sense of realism.

Considered as a whole, I think The Red Turtle is a largely successful experiment in filmmaking, notwithstanding my reservations about the story. De Wit and his team deserve full credit for committing to their unusual concept, embracing its limitations, and producing a work of great visual artistry. We can be glad Ghibli took a chance on this project.

Post-Script: The Red Turtle had its genesis when Hayao Miyazaki saw de Wit’s Oscar-winning short film Father and Daughter. Miyazaki reportedly said of the Dutch filmmaker, “If one day Studio Ghibli decides to produce an animator from outside the studio, it will be him.”

Ghibli reached out to de Wit and eventually co-produced the movie along with Wild Bunch, Ghibli’s European distributor, among other companies. Isao Takahata was apparently a major influence on The Red Turtle‘s development. The Ghibli co-founder is credited as the movie’s “Artistic Director,” and de Wit has spoken appreciatively of the feedback he received from Takahata.

While an outlier with its largely non-Japanese filmmaking team, The Red Turtle still qualifies as a Ghibli production. Since my topic in this retrospective has been Studio Ghibli movies, not the movies of any particular director or nation, the movie accordingly earns its slot here.

(That being said, I should acknowledge that before I finish this retrospective I will have to review one movie that is not, strictly speaking, a “Studio Ghibli work”…but we will get to that when the time comes.)

Post-Post-Script: If Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson are still planning to make another Tintin movie, I beg them to follow Miyazaki’s lead and somehow get Michael Dudok de Wit involved in the project! He is definitely the man to properly bring Herge’s work to the screen.

Leave a comment