Next in my Studio Ghibli retrospective comes The Tale of the Princess Kaguya.

I would like to take a moment to talk about Isao Takahata, one of Studio Ghibli’s original founders. Although he has been overshadowed by his more prolific and famous co-founder Hayao Miyazaki, Takahata’s work and life are no less worthy of attention.

The youngest of seven children, Takahata spent part of his boyhood in Okayama and lived through the United States’ firebombing of that city during the Second World War. He later recalled how he and his older sister fled through flaming streets, dousing themselves with water to avoid being burned. His sister was wounded, but they both survived. Their family home burned to the ground and, as Takahata explained, in the bombing’s aftermath, “I saw so many bodies. I was so horrified, I was trembling and my teeth were chattering.” He would draw on these experiences in his master work, Grave of the Fireflies.

After the war, Takahata went to the University of Tokyo. His original field of study was not filmmaking, though, or even art, but rather French literature. However, Takahata’s admiration for the French poet Jacques Prévert led him to watch the animated film Le Roi et l’Oiseau (1952), for which Prévert had written the screenplay. The experience prompted Takahata to go to work for the Toei Animation company, where he became a director and met Miyazaki.

Takahata and Miyazaki developed a somewhat sibling-like relationship; Miyazaki once teased his colleague over his slow work pace and limited output by calling Takahata “a slugabed sloth.” Also, unlike Miyazaki, Takahata did not draw animation for the movies he directed. Yet not drawing, and thus not having a personal style, perhaps provided him with more freedom to experiment creatively: every Ghibli movie Takahata directed was dramatically different in both its content and visual style.

Takahata’s habit of artistic experimentation continued with The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013), which he directed and co-wrote with Riko Sakaguchi.

The movie is a re-telling of “The Bamboo-Cutter and the Moon Child,” a Japanese folktale dating back to the 10th century. As in the original tale, the story begins with a humble, childless bamboo cutter who discovers a mysterious, miniature girl inside a bamboo stalk. The cutter and his wife raise the girl as their own child.

The girl, whom the couple names Princess Kaguya (“Princess Moonlight”), grows with unnatural speed into a young woman of extraordinary beauty. The bamboo cutter and his wife soon grow wealthy while their adopted daughter finds herself courted by the most renowned men in the land. Yet in keeping with her otherworldly origins, Princess Kaguya is not all she seems and has an unexpected destiny awaiting her.

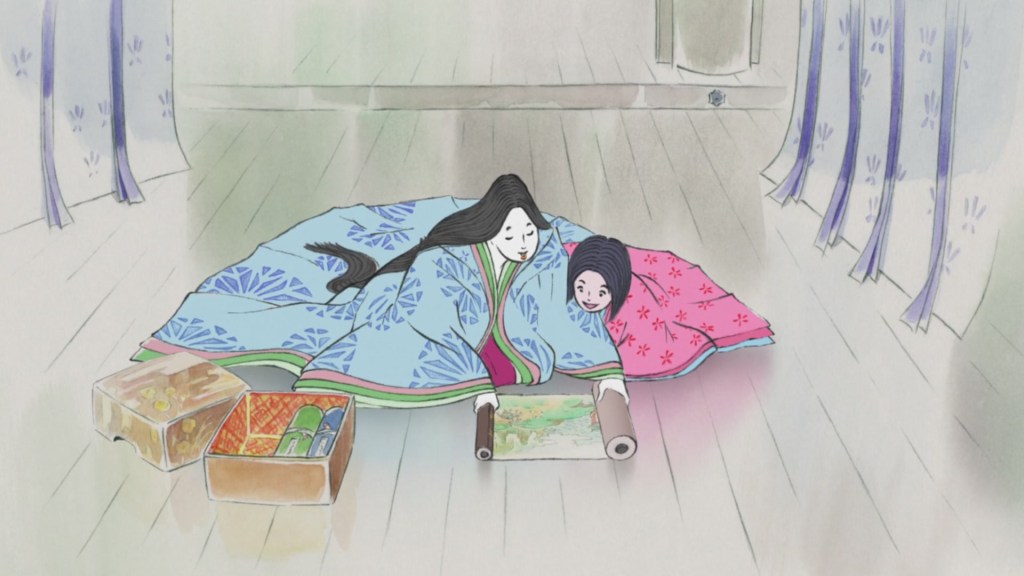

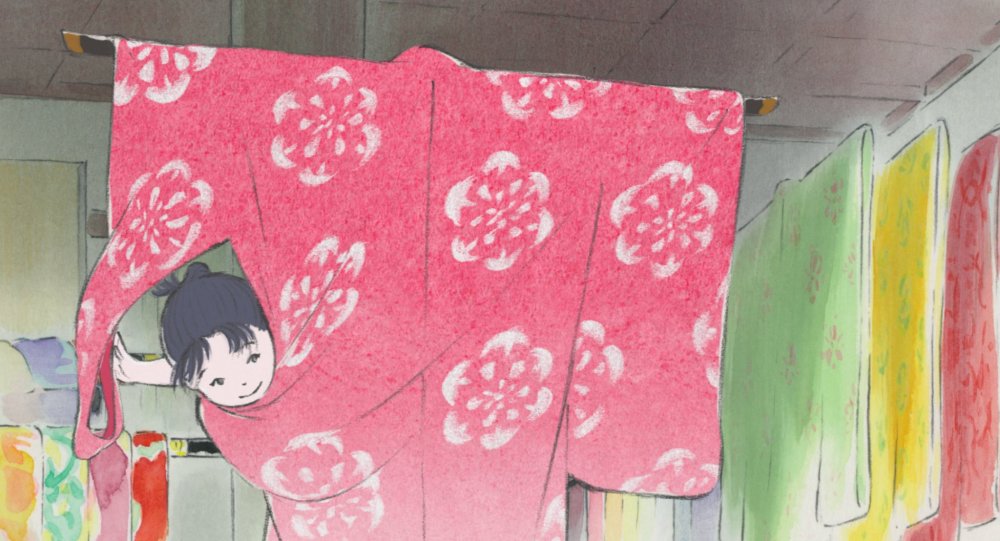

To render this fairy tale on screen, Takahata and his animators use a new visual style, one wholly different from recognizable anime conventions. The animation has a seemingly simple, even rough, look that resembles sketches done in heavy pencil or charcoal or perhaps watercolor paintings.

Images are an assembly of black lines, gray shading, and light colors. The borders around characters, objects, and places are frequently blurry. Character design is minimalist, with faces often made up of a few lines and shapes; when characters are in the background or viewed in long shot, their faces become mere dots and scribbles or even disappear altogether.

This style is rich with similarities to other art. Shots of landscapes recall Japanese and Chinese “mountain and water” paintings. I was also reminded of Impressionist paintings as the animators used an array of indistinct shapes to create a distinct overall effect: an array of gray streaks and shadowy outlines powerfully conveys a rainy day.

Even while they evoke classical art, though, the images have the quality of a child’s drawing, right down to the use of large amounts of blank space in shots, like paper that has not yet been colored in.

The movie’s animation also recalls previous Takahata works. White space was a recurring fixation for Takahata, who used it extensively in his earlier movies, Only Yesterday and My Neighbors the Yamadas. The minimalist character design is also a legacy of Yamadas. That movie’s sketchbook-esque interlude with the biker gang similarly seems to have influenced Princess Kaguya’s look.

Even while the filmmakers try out a generally new look, though, some crucial aspects of traditional Ghibli animation are still on display here. Composition is as painterly as ever, with characters, objects, buildings, and landscapes beautifully arranged in the foregrounds and backgrounds, sides and centers of shots.

As in Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, light is also rendered very well here, especially in early country scenes where we see the dappled rays of both dawn and dusk gorgeously illuminate the bamboo forest.

The Ghibli animators also continue to show their knack for capturing reflections in polished floors.

After the beauty of this new animation style, the movie’s greatest strength is its portrayal of the preternatural heroine’s early life. The first half hour or so is a lovely series of vignettes of young Princess Kaguya learning to walk, exploring the countryside around her home, playing with other children, befriending a village boy named Sutemaru, and getting into mischief such as stealing melons from a farmer’s field.

These scenes evoke that half-delightful, half-dangerous quality of childhood when every experience, being new, is an adventure. A nice, true-to-life touch is how the toddler Princess Kaguya, chasing a hopping frog, is unfazed by taking a tumble onto the ground but immediately starts crying on losing the frog.

These great little moments continue up to the point the bamboo cutter moves his family from the country to a mansion in the city. The initial scene in their new home, when Princess Kaguya realizes and then celebrates their new-found wealth, is perhaps the best in the movie. Her exuberance as she runs around the mansion and tosses her fine new colored robes around in a kaleidoscopic way is truly joyful.

After this point, however, the movie begins to stumble. Part of the problem is that the physical move away from the countryside takes away some of the visual interest. The bigger problem, though, is that Takahata and Sakaguchi do not have as sure a grasp of storytelling as the animators do of the visuals.

After the family’s move to the city, the remaining run time is mostly taken up with the bamboo cutter’s attempts to make Princess Kaguya into a properly behaved young woman and the attempts by five aristocrats to win her hand in marriage. This material could be interesting if handled with subtlety or complexity. That is not the route the filmmakers take, however.

Let me pose some questions about how the movie might unfold from this point on and you try to answer based on your past movie-going experiences. Will Lady Sugami, the governess retained to teach Princess Kaguya etiquette, be a stuffy, imperious taskmaster who does not understand our heroine’s true needs? Will the aristocratic suitors be arrogant, selfish jerks or buffoons who are obviously all wrong for our heroine? Will the poor but stalwart country boy Sutemaru be a better match? Will upper-class life be stultifying and repressive compared to the simple joys of life in the country? Will any cliché be left out?

Such trope-heavy plot points are not very interesting to watch. Granted, these later passages of the movie have their memorable moments. A dreamy sequence where a distraught Princess Kaguya runs into the forest pushes the visual style to a new extreme. The drawings of the fleeing girl become rougher and more jagged until great dark lines stab across the screen, as if the artist is simply slashing at the picture with a crayon.

In another, happier but still bittersweet, scene, our heroine enjoys a shower of cherry blossoms.

Also, the inappropriate suitors’ attempts to win over Princess Kaguya offer some flashes of humor. I liked a sequence involving a long, self-aggrandizing, and false story one suitor tells; his little bow of polite embarrassment after being unmasked as a fraud is especially funny. Another suitor seems to be different from the others and offers what appears to be a sincere declaration of love only to be revealed, in an unexpected way, as yet another phony. (In contrast, a different suitor’s story ends with a tonally unpleasant mixture of the macabre and the slapstick that probably should have been left out.)

Aside from a few high points, though, the movie’s later scenes just keep making the same obvious points: repression is bad, the suitors are bad, and Princess Kaguya is really unhappy. This approach is boring and dilutes the story’s emotional impact, especially when it unfolds at as slow a pace as this movie does. The original story about Princess Kaguya is not a long or elaborate one. The version I read took up all of 11 pages and was still somewhat repetitive. Meanwhile this movie adaptation is over 2 hours long and the filmmakers do not justify that length. (Consider that when Disney adapted the similarly uncomplicated tale of Cinderella in 1950, that movie did not even crack 80 minutes. Now imagine that Walt had padded that out with an extra hour and 20 minutes dwelling on how unhappy Cinderella’s life at home was and how horrible her stepmother and stepsisters were.)

This long movie’s ending does not quite land. Takahata and his team pull out all the stops visually and musically for what is supposed to be a big emotional climax. Yet despite the impressive artistry, I was not as moved as I was supposed to be. My main difficulty with enjoying the scene was some pretty big, obvious questions that the characters were not asking. Such avoidance is a shame, as the scene would actually have been more interesting and poignant had these realities been faced.

The English dub works fine. As Princess Kaguya, Chloe Grace Moretz is especially good at conveying the character’s later unhappiness with her cold, dead delivery. As her adoptive parents, James Caan and Mary Steenburgen convey those characters’ warmth and humanity.

The soundtrack contains some great music in both composer Joe Hisaishi’s soaring theme “The Sprout” and the melancholy song “Tennyo No Uta.”

The whole movie is a visual wonder to behold, but probably my favorite image is a relatively simple one: the baby Princess Kaguya at home with her mother and father. Here we get a characteristically perfect composition that exudes gentle domesticity.

In true Ghibli fashion, the movie abounds in humanizing details. I don’t think I can pick a favorite one. Rather, I will list a handful I appreciated:

- The bamboo cutter, upon first seeing Princess Kaguya in the forest, pauses to wipe his hands off before picking her up.

- When Princess Kaguya and Sutemaru eat the stolen melon, she grimaces and coughs in reaction to the seeds’ sourness.

- The newly wealthy bamboo cutter is unused to his fine new hat and keeps knocking it against door lintels.

- When Princess Kaguya receives a visitor, Lady Sagami, who is seated behind her, reaches around to straighten the corner of the girl’s robe (later, an attendant performs the same service for the visiting suitors).

- Princess Kaguya, bored at being kept in seclusion, idly taps her finger against a dish on the floor next to her.

I would judge The Tale of the Princess Kaguya an odd hodge-podge of strengths and weaknesses. Takahata and his team produced a work of extraordinary craftsmanship and beauty that does not quite work dramatically. Yet the good parts are so good that I wish the whole worked better.

I especially wish the movie worked better because, sadly, this would prove to be Takahata’s last work. He died five years after the movie’s release.

In his time at Studio Ghibli, Isao Takahata directed five movies. All of them were interesting and visually unique. Two of them, Grave of the Fireflies and Only Yesterday, were truly great. His movies had a melancholy, often tragic quality, but also showed a compassion for the characters and their struggles. Across all his works, Takahata consistently engaged in bold artistic experimentation. It is an impressive legacy.

Leave a comment