In the same month that brought the 80th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, I examine the life and work of a man who helped make that catastrophic event possible. Next in my Studio Ghibli retrospective, I look at The Wind Rises.

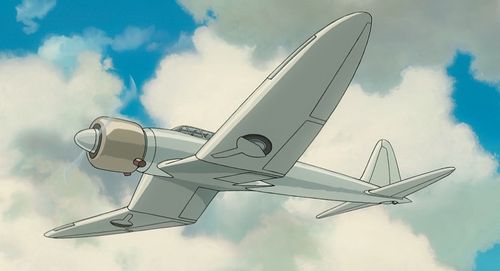

Jiro Horikoshi was a Japanese aeronautical engineer who went to work for Mitsubishi in the late 1920s. While working for the company, he designed for the Japanese Imperial Navy what would become known as the A6M Zero fighter plane. Characterized by a long flight range and extreme maneuverability, the Zero became a significant part of Japan’s war effort during the Second World War. Zero fighters played a role in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and were much feared by Allied aviators, who advised: “Never dogfight a Zero.” In his book on World War II, historian John Keegan commented that for much of the US-Japanese war the Zeros were “the best shipborne fighters in the world.”

Horikoshi was undoubtedly a brilliant engineer. But what was the real meaning of his work?

This question lies at the heart of The Wind Rises (2013), written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki. The movie differs from Miyazaki’s previous work in lacking any overtly magical or supernatural elements and in being far more somber, even downbeat, than usual. As a lover of aviation with strong peace-minded convictions, Miyazaki clearly sees a deep tension between Horikoshi’s extraordinary gifts and the destructive ends to which he applied them. The Wind Rises tries to give due weight to both sides of Horikoshi’s life and legacy.

Has Miyazaki made a successful movie on this complex topic? Yes, up to a point. Overall, he captures and balances this story’s simultaneously exhilarating, beautiful, and tragic aspects. The movie is especially strong when it relies primarily on visual story-telling to make its points, which it often does. Parts of the Wind Rises are as good as anything Miyazaki has ever done. Yet the movie is repeatedly dragged down both by a tendency to spell out its themes through dialogue (falling into the “telling” rather than “showing” trap) and an occasional murkiness about Horikoshi’s character that comes across as more confused than legitimately ambiguous.

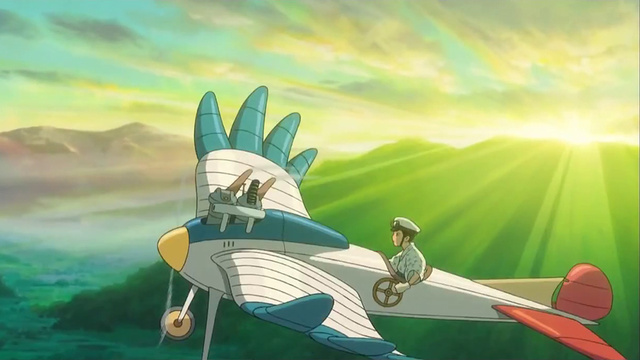

The Wind Rises covers a little over 20 years of Horikoshi’s life, from his early adolescence in 1918 to the completion of the Zero in 1940. When we first encounter the young Jiro he is an imaginative boy who dreams of flying planes and idolizes the Italian aeronautical engineer Gianni Caproni. In his inner reveries, which are rendered on screen, Jiro converses with the imagined Caproni and inspects the Italian’s aerial creations. Prevented by poor eyesight from ever being a pilot, Jiro decides to follow in his hero’s footsteps by designing planes instead.

We subsequently see the older Horikoshi go from engineering school to a job at Mitsubishi that includes a trip to the Junkers aircraft factory in Weimar Republic-era Germany. Eventually he receives the commission to design the Navy’s new fighter plane.

As he pursues his engineering work, we also get to know various notable people in Horikoshi’s life: his younger sister, Kayo, a spirited, aspiring doctor; a fellow engineer, Honjo, who takes a more cynical attitude toward life than his dreamy colleague; and their Mitsubishi supervisor Mr. Kurakawa, a pint-sized man with a gigantic temper (but a good heart). Most important, we meet Naoko Satomi, a sweet, artistic young woman from Tokyo with whom Horikoshi conducts a long-running courtship. The two like each other but their relationship’s future is clouded by Naoko’s tuberculosis.

Studio Ghibli movies’ most distinctive feature is their visuals, and here The Wind Rises does not disappoint. Because aviation is at the heart of this story, we get plenty of scenes of planes in flight that show off these machines’ grace and grandeur. Miyazaki and the other Ghibli animators have a well-practiced skill for simulating camera movement and use this technique to good effect so the viewer seems to soar, sweep, and glide through the air along with the planes.

Even when the planes are grounded, they are impressive. The moment when a hangar at the Junkers factory slowly opens its doors to reveal a massive plane has an appropriately epic feel, like King Kong being revealed.

In the scenes where Mitsubishi planes are wheeled out onto airfields for test flights, Jiro and the workers march rhythmically along so the tests take on a ceremonial quality.

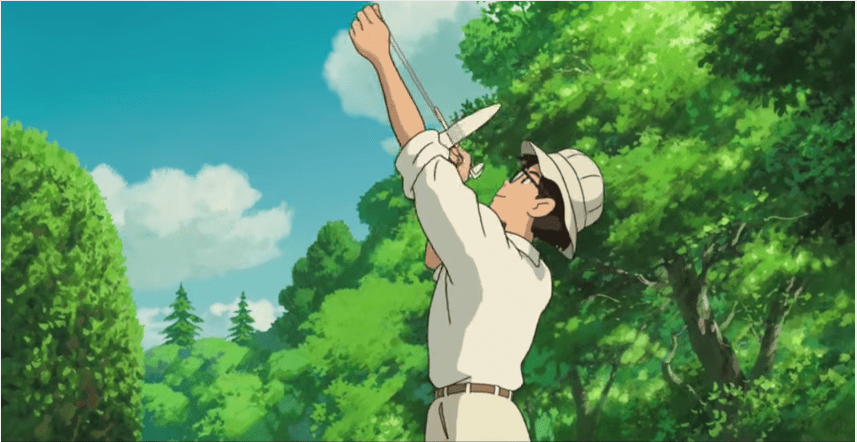

Being animated, The Wind Rises has the added visual advantage of not having to adhere to strict realism in dramatizing flight. In addition to real-world test flights, we are shown the flying planes that constantly fill Horikoshi’s mind as the movie shifts seamlessly from imagination to reality and back. As our protagonist labors over blueprints and calculations, we see, in flight, the plane he is envisioning and a rushing wind sweeps over Horikoshi and his desk as if he were airborne himself. As he realizes the weaknesses of his possible design, the envisioned plane crashes to the ground and Horikoshi and his desk go crashing back into reality with it.

Later, when he explains a new design to his fellow engineers, the roof of their workshop briefly becomes blue sky and the proposed plane flies overhead, to the other engineers’ amazement.

Striking though the aviation imagery is, I was even more impressed by how the filmmakers render various types of light, both natural and artificial. Appropriately for a movie so focused on the sky, we get memorable shots of the sky in various lights: the salmon pink and rich yellow-gold of morning, the deep red-orange of sunset, the washed-out platinum of a winter’s day. The rendering of sunbeams as they enter through windows or gaps in tree branches captures how sunlight can look almost solid at times.

In one night-time scene, a shop’s open doorway and a street lamp cast a yellow light on the darkened street that somehow makes the street look all the more empty and forlorn. In another night-time scene, a paper lantern gives those illuminated by it a spectral glow.

That a Ghibli movie looks amazing is always gratifying but hardly surprising. Most fans would expect no less. What is more surprising is the interesting use of sound design. At key moments, the filmmakers use what sound like human voices to provide the noises of the inanimate world. At one point, a plane slowly revving up its engine resembles a human whine of excitement. The most memorable use of this approach comes during an extended sequence dealing with Horikoshi and Naoko first meeting amid the chaos of the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. The earth’s rumblings sound like the breathing and roaring of some great beast. In both cases, the sounds heighten the emotion of the scene. The airplane’s “excitement” mirrors Horikoshi’s, while the earth’s “roars” deepen the sense of danger.

However, as beautiful as it looks and sounds, The Wind Rises ultimately succeeds or fails on the basis of its portrayal of Jiro Horikoshi. For the most part, the movie gives us an intriguing, powerful portrait of an immensely talented, rather child-like engineer who is disturbingly uninterested in the implications of his work.

In many ways, the on-screen Horikoshi is a decent, even admirable man. Compared to his temperamental sister and co-workers, he is fairly even-tempered and rarely displays anger. We repeatedly see him show kindness and concern for others. As a boy, he intervenes to protect a younger child from bullies. During the Kanto Earthquake, he helps get Naoko and her older sister to safety, carrying the injured sister on his back. As an adult, he offers some food he has bought to a group of poor children on the street. When the ill Naoko is confined to her room, he entertains her from outside with a game of (expertly designed) paper airplanes—it’s a gesture that is both an expression of concern and an engineer’s version of a romantic serenade.

While Horikoshi may be unfailingly kind to those in his immediate circle, though, he does not ask questions about the big picture. After Horikoshi’s encounter with the poor children, his colleague Honjo points out the perversity of Japan’s government spending so much on planes and other weaponry while the country’s people go hungry. Horikoshi’s reaction? He doesn’t really have one; he simply goes on as before. When he visits Germany, Horikoshi witnesses the police chasing down a man, a pursuit that leads to the police smashing up windows and shops along one street. While the episode takes place before the Nazis’ rise, we are clearly meant to think the police officers are up to no good. Yet Horikoshi does not ask questions or show much interest. During a later scene when the Imperial Navy commissions the Zero fighter, we hear the naval officers’ voices from the bored Horikoshi’s perspective as merely a gabble of incoherent sound. The effect is superficially funny, but it also raises the question: is our protagonist really paying attention to what he is being asked to do?

All this is uncomfortable, challenging material that works well dramatically. The most potent illustration of Horikoshi’s harmful obliviousness is his unfolding relationship with Naoko.

I was initially not sold on this romance element of the movie’s story, which seemed so far removed from the central issue of building the Zeros. Was this business with the consumptive fiancée just thrown in to pluck our heart-strings? Yet as the movie neared its climax and the overall tone grew darker, the full significance of the Jiro-Naoko relationship became clear. The romantic “subplot” was actually close to the heart of the movie and eventually drove home the central theme in a crushingly sad way. This aspect of The Wind Rises is not subtle, but it is powerful.

I also appreciated the no-less powerful way the filmmakers foreshadow events beyond what is directly shown on screen. The brutality of German police I mentioned above is never explained or directly referred back to, but it provides an ominous glimpse of what is coming in a few years’ time—the scene serves as a kind of proto-Kristallnacht. The Kanto Earthquake, with its resulting firestorm in Tokyo and subsequent desolate cityscape, prefigures what the viewer knows will be Japan’s ultimate fate in the future, thanks in part to Horikoshi’s work.

If The Wind Rises dealt with the dire consequences of war and preparations for war purely in this indirect, symbolic way, then the movie would be a masterpiece or close to it. However, Miyazaki and his team regrettably do not stick to this approach. As a result, the movie and Horikoshi’s characterization specifically get thrown off.

Not content with foreshadowing and relying on viewers’ own basic knowledge of history, The Wind Rises gives us multiple scenes of characters explicitly telling us what is going to happen. In Horikoshi’s visions of Caproni, the Italian engineer warns him that airplanes inevitably get used as weapons of war. Later, a German tourist (presumably a dissident or refugee) Horikoshi meets warns him that Germany and Japan will inevitably meet with disaster if they continue their current war-like course. Still later, Honjo tells Horikoshi something similar. Also, some thematically important details about Jiro and Naoko’s relationship are revealed not through their actions but simply by a character relating them in an expository speech.

All this is pretty pedestrian writing, not to mention redundant: much of what we are being told has been made clear or could be made clear in less obvious ways. The German visitor, Castorp, is especially gratuitous, having no function other than to offer portentous comments. When he first appeared, I thought the character would somehow influence Horikoshi or play a significant role in the plot, but no such luck: he just does his Teutonic Cassandra bit and disappears.

Further, what does this repeated on-the-nose dialogue mean for our understanding of Horikoshi’s character? Regarding him as naïve or oblivious becomes much harder when so many people are unambiguously warning him about the negative consequences of his actions. In particular, the warnings from “Caproni” are puzzling as these are really just Horikoshi’s imaginings of what the Italian would say to him. Does this mean Horikoshi is fully aware of how harmful his actions are but is consciously choosing to follow this course anyway? As he tells his imagined Caproni, “I just want to make beautiful airplanes.” So is he not oblivious but rather selfish and callous?

But if Horikoshi is meant to be understood as a more sinister figure, what then are we to make of the movie’s (completely unnecessary) epilogue? Here, we once again get more dialogue reminding us of what the movie’s stakes and themes are. And then…the movie pretty much lets Horikoshi completely off the hook. Miyazaki gives us a vague, hollow bit of absolution that would be unconvincing if Horikoshi were guilty only of ignorance, let alone the conscious wrong-doing the movie implies. Maybe something more coherent was intended here, but it comes across as if Miyazaki could not make up his mind about what to say.

The movie benefits from a strong English voice cast. As Jiro Horikoshi, Joseph Gordon-Levitt gives a nicely understated vocal performance that is earnest but never seems to be trying too hard. This restraint fits the character’s ever-so-slightly blank manner and temperament. In contrast, we have Martin Short, as the diminutive boss Kurakawa; Stanley Tucci, as the dream-vision Caproni; and Werner Herzog, as Castorp. All give enjoyably hammy performances that balance the movie’s self-contained protagonist.

Beautiful images abound in The Wind Rises. I like a shot of Naoko painting a canvas in an open green field; I like a shot of a house sheltered by a flowering cherry tree.

Most of all, though, I like the lovely but melancholy shot of a mountain seemingly floating above the clouds that tilts down to reveal a wintry landscape, including rows of bare, leafless trees, at the mountain’s foot.

For whatever reason, I did not notice as many humanizing details here as in other Ghibli movies, but one did stand out. Horikoshi, reacting to an emergency and in a state of extreme emotional distress, rushes into a house—but still instinctively kicks his shoes off at the entrance. Even in crises, old habits die hard.

My verdict on The Wind Rises is that it is a beautiful, often emotionally affecting movie that does not live up to its full potential. Nevertheless, even a lesser accomplishment from Hayao Miyazaki is still usually very good, and that holds true here as well.

Leave a comment