Having just finished a Tokyo Olympics this month, let’s look back at the last time the Olympics were held in that part of the world. Next in my Ghibli retrospective, I review From Up on Poppy Hill.

Among Ghibli fans, one occasionally hears the plaintive wish to live within a Ghibli movie, or perhaps some variant of the query “If you could, which Ghibli world would you live in?” For my part, my answer would be “I would live in the world of From Up on Poppy Hill.”

From Up on Poppy Hill (2011), directed by Goro Miyazaki from a screenplay by Hayao Miyazaki and Keiko Niwa (and based on a manga by Chizuru Takahashi and Tetsuro Sayama), tells a very simple, slice-of-life story about a group of teenagers in 1963-era Japan. I wouldn’t call the movie “great” or even one of my overall favorite Ghibli films. However, the filmmakers capture an extraordinarily charming atmosphere and mood here that I find irresistible and would love to inhabit for a long time.

Set in Yokohama, a port city not far from Tokyo, the movie follows high-school student Umi Matsuzaki. Umi lives along with her younger sister and brother in their grandmother’s large house on the titular hill overlooking Yokohama’s harbor. Their mother is away in the United States doing graduate studies. Their father died during the Korean War; a naval officer, he was transporting supplies to the forces in Korea when a mine sunk his ship. Now Umi and her family share the grandmother’s house with various boarders, with Umi acting as a kind of unofficial household manager.

We begin with Umi’s morning routine, as she rises early to cook breakfast for the household before heading off to school. She also enacts a significant ritual: at a flag pole in the house’s garden, she raises nautical signal flags conveying the message “I pray for safe voyages.” Having been taught nautical signaling by her father, Umi still sends out this message into the world.

At her high school, trouble is brewing over the “Latin Quarter,” a shambling, run-down old building that the school’s male students have used for generations as the headquarters for their various clubs and extracurricular activities. The school administration wants to tear down the decrepit clubhouse to build some new structure.

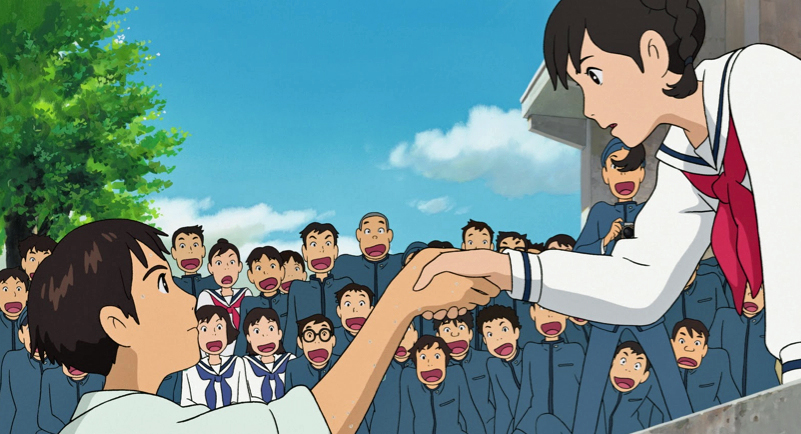

The boys are determined to resist, though, and they stage a public gesture of defiance. One boy, the dashing Shun Kazama, jumps from the Latin Quarter roof into a nearby water tank to draw attention to the building and the students’ struggle to preserve it. This stunt leads to an awkward encounter between Umi and the soaked Shun.

Umi thinks the whole business is silly, but her younger sister Sora is star-struck and soon draws Umi into the quest to preserve the Latin Quarter. This effort involves the herculean task of fixing up the place and the no-less-daunting challenge of changing the relevant authority figures’ minds. As she spends time with Shun working on this quixotic endeavor, Umi begins genuinely to care, both about saving the clubhouse and also about Shun. Meanwhile, she gets clues that a ship in the harbor is returning her morning signals. The connections among all these events soon become clear.

The plot contains some additional complications, which I will get to, but the plot isn’t the main interest here. I will try to explain what else makes the world of From Up on Poppy Hill so appealing.

Let’s start with the music. I haven’t talked that much in this retrospective series about the music in Studio Ghibli movies, but music has been a consistently strong part of the studio’s creations. Most Ghibli movies feature scores by the great Joe Hisaishi, who has composed unforgettable themes for Castle in the Sky, Princess Mononoke, Howl’s Moving Castle and many others. From Up on Poppy Hill, though, is in a class of its own.

The music for From Up on Poppy Hill was done by Satoshi Takebe, who took a very different approach from the orchestral scores favored by Hisaishi. Here the musical pieces, performed on instruments such as piano and melodica, have a relaxed, jazzy feel (with perhaps also a hint of the pop music that would invade Japan a few years after the movie’s events). One could imagine hearing these pieces performed in a nightclub. Their tone and tempo vary from the upbeat to the more wistful, yet they always have a kind of cool confidence to them—like a wry smile in musical form.

Along with the purely instrumental pieces, the soundtrack features some full-fledged songs. Two, the jaunty “Breakfast” and the romantic “When First Love Is Born,” were composed by Hiroko Taniyama with lyrics by director Goro Miyazaki and were beautifully performed by Aoi Teshima.

The movie also has diegetic performances of period music, such as “Ue wo Muite Arukô” (familiar to some Americans as “Sukiyaki”) and “Shiroi hana no saku koro,” which some mischievous students perform in the movie.

The whole soundtrack is a delight. More than any other Ghibli movie, From Up on Poppy Hill has music that could work as a stand-alone album, purely apart from any cinematic associations.

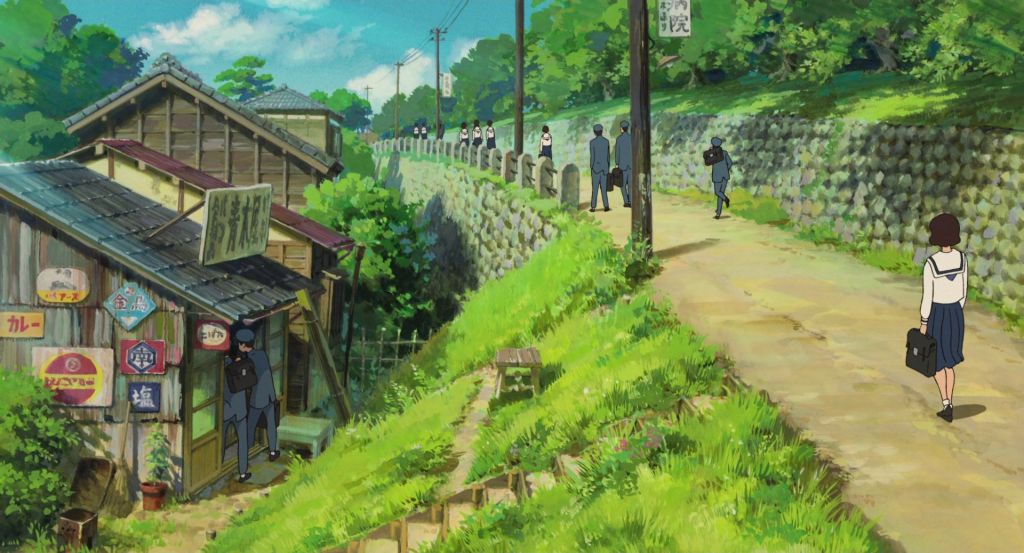

To accompany this music, Miyazaki and his animators create a no-less-appealing environment for the story. By setting the movie in the past, in a moderately sized port city, the filmmakers have found what is perhaps unique among Ghibli movies: a location well balanced between urban and rural, between civilization and nature. Yokohama is recognizably a city, with houses, schools, and marketplaces, yet trees and green spaces are abundant and the sea is an inescapable part of daily life. The result is a nice equilibrium between the metropolis of Whisper of the Heart and the bucolic countryside of My Neighbor Totoro.

Certain visual touches are especially effective in conveying the reality and beauty of the movie’s Yokohama. The Ghibli knack for gratuitous details is used here to fill scenes with people. The background and foreground of shots are constantly occupied by characters, often moving in multiple directions at once.

During school scenes, Umi, Shun, or Sora might talk in the foreground while groups of other students talk or groups of athletes practice in the background. When characters walk up or down the road running from the top of Poppy Hill to the harbor, almost invariably some other city-dweller is traveling along the road in the opposite direction. When Shun and Umi visit the open-air market down by the harbor, the shots of the marketplace are filled with people shopping or on other errands in the backgrounds or corners of the frame. (In a nice throwaway moment, Shun has to swerve his bicycle at one point to avoid a man walking his dog.) A late scene set in a Tokyo office building is similarly crammed with office workers.

This constant presence of animated “extras” adds visual interest by giving shots depth and movement. More important, they provide bustle, a sense that this setting is full of activity and life. Sometimes these busy visuals also provide humor. For example, during a luncheon at the grandmother’s house, we see the guests gathered at a long table. People at either end of the table talk enthusiastically while in the middle Umi’s younger brother and one of the boarders silently but no less enthusiastically stuff their faces.

By far the most visually impressive of the movie’s many crowded locations is the creaky old Latin Quarter building, which climbs multiple levels up to a clock tower. The building’s dirty, cluttered interior has been divided up by the boys’ clubs into something approaching miniature fiefdoms. The student groups have not only occupied every room but have built wooden huts or set up tents to house their activities. Like the rest of the movie’s locations, the Latin Quarter bustles with various activities: boys are declaiming, doing scientific experiments, playing on a ham radio, and the like. It’s a memorable, funny setting.

Certain colors add warmth to the movie’s look. During night scenes, light from storefronts or streetcars casts a soft yellow glow. During day scenes, we get an impressionistic sky of blue, white, red, and gold.

Beyond great music and engaging visuals, From Up on Poppy Hill also offers that rare pleasure, a plausible, relatable portrait of teenage life. The movie (for the most part) avoids big, high-stakes conflict or melodrama and instead gives us the stuff of everyday high school life: classes, extracurriculars, and daily domestic routines. In this low-key world, saving a beloved clubhouse and quietly budding romance are about the most serious concerns for our characters, which feels true to life. Compare this to the life of teenagers in a movie such as, say, Makoto Shinkai’s 5 Centimeters per Second, which is entertaining but in which the drama and angst have been cranked up to 11 in a way that is not always believable.

In particular, From Up on Poppy Hill captures an aspect of the high-school experience that is very real yet so rarely featured in movies: how adolescents use their hobbies or intellectual pursuits to define their identities—and to show off. We see this in the portrayal of the boys’ club activities and also in a staged debate among the male students. These moments are played very broadly—a philosophy enthusiast self-consciously weeps while talking about seeking wisdom; the debate degenerates into an open brawl—yet they contain a recognizable truth.

Whether they are showing us astronomy students engrossed in their telescope or a pair of boys earnestly discussing how to revive interest in archaeology, the filmmakers clearly understand something crucial. An overabundance of hormones can express itself not only in sports or amorous pursuits but in taking one’s interests, and oneself, Very, Very Seriously. Indeed, some of the students’ dialogue and behavior is so pompous that it reminded me of myself at that age.

(Not that I was ever as cool as Shun in high school; Shun’s rather nerdy friend Shirou seemed oddly familiar, though.)

(Actually, Shirou is also cooler than I was in high school.)

Oddly enough, From Up on Poppy Hill reminds me of another movie with a great soundtrack about teenagers in the early 1960s: George Lucas’ American Graffiti. Granted, the two movies are obviously quite different in certain respects: they occur in different countries; From Up on Poppy Hill does not take place in a single night as American Graffiti does and lacks the focus on car culture that is so central to Lucas’ movie; and so on. Nevertheless, they share a similar light touch and loose plotting, the continuous use of music to create atmosphere, a plausible portrait of teenagers, and a curious combination of historical and cultural specificity with broad relatability. I did not grow up in either urban Japan or small-town northern California in the early 1960s, yet I can identify with the characters in both movies. (For a great commentary on American Graffiti and its relatable portrait of adolescence, see the Royal Ocean Film Society video essay on the movie, which influenced my own thinking on both these films.)

From Up on Poppy Hill and American Graffiti share something else significant: an underlying sadness created by off-screen history. In American Graffiti, that history is the future events that will soon shape (or destroy) the characters’ lives, such as the Vietnam War and other tumult of the late 1960s. That movie’s famous emotional sucker-punch of an epilogue casts the light-hearted events that have come before in a new light.

By contrast, in From Up on Poppy Hill, the weighty history is the past events that have already shaped our characters’ lives: the Korean War that killed Umi’s father and, still more, the Second World War that devastated Japan and radically altered its society. World War II is not often explicitly discussed in the movie—although it comes up a few times, including in one mention of a recognizable city name—yet its presence hangs over everything.

On the surface, the Japanese society we see in the movie is as buoyant and optimistic as our young protagonists, looking forward to a bright future symbolized by the following year’s Tokyo Olympics. However, just as Umi’s life is clouded by grief over her father, Japan’s past provides a somber background for the story. The struggle to preserve the old Latin Quarter clubhouse even as the school modernizes thus illustrates in microcosm the larger theme of reconciling past, present, and future.

Having spent so much space praising From Up on Poppy Hill, a reader might well ask why I refrained in the opening from calling the movie great. Here we must get to those additional plot complications that I mentioned above and that I fear are the movie’s biggest creative misstep.

If From Up on Poppy Hill were simply about Umi, Shun, and the other students’ daily lives and the biggest on-screen drama was simply trying to save the clubhouse, then the movie would be first rate. Alas, Miyazaki and company gave in to the temptation, so common in movie romances, to create additional conflict by including an obstacle to Umi and Shun’s relationship. Moreover, the obstacle is a very, er, interesting one that does not typically turn up in most romantic stories and that tends to elicit squirm-inducing discomfort (I will give the filmmakers some credit for originality here, even if I cannot endorse the result).

I understand why this plot twist is included: it reinforces the theme of having to face the past before proceeding into the future. Still, this element throws off the movie in multiple ways. It injects extreme contrivance into what is otherwise a realistic story. It adds awkwardness to a generally sweet atmosphere. And it leads to Umi and Shun expressing sentiments that do not seem very believable under the circumstances. The movie happily does not spend too much time on this plot point and the matter is ultimately resolved in a reassuring way. Still, the whole business strikes a sour note and prevents From Up on Poppy Hill from working as well as it should.

The English dub is good, although one of the odder ones. Other Ghibli dubs might be faulted for including big, or at least trendy, names to attract American audiences, regardless of whether they were appropriate for the roles or not; this is how we sadly ended up with Billy Crystal as Calcifer in Howl’s Moving Castle. Here, though, the English voice cast is populated by established but not super-famous actors—Jamie Lee Curtis, Beau Bridges, Gillian Anderson, Chris Noth, and others—none of whom have very large roles or are even particularly recognizable. These actors are all effective, with Bridges in particular doing good work as a genially gruff businessman, but I am not sure what the casting logic was. Did the dub directors think that having Bruce Dern in a bit part would provide the raw star power the marketing team needed?

While the dub casting might be slightly eccentric, the central roles are well cast. Sarah Bolger, as Umi, gives a refreshingly direct performance that expresses our heroine’s common sense. Just watch the moment when the fresh-faced Shun claims to have cut himself shaving and listen to her flatly skeptical delivery of “Shaving?” As Shun, the late Anton Yelchin has a throaty delivery that sounds both appropriately callow and sensitive. Also, I must single out from the supporting cast the actor who performs the pretentious philosophy student: Ron Howard, a star of American Graffiti! I feel vindicated.

My choice for favorite image is one of Umi walking over a bridge in the rain, while below the bridge a streetcar trundles along. The shot contains the movement along multiple planes characteristic of the movie’s busy visual style—Umi is walking parallel to the camera as the streetcar moves toward it. Umi’s red umbrella provides a splash of color amid an otherwise dark background. The overall effect is somewhat lonely yet also peaceful.

Among the movie’s humanizing details, Shun avoiding the man and his dog is a good one. I also like a moment where Umi, running through her house in her socks, slides along the floor when she abruptly tries to stop.

I wish Goro Miyazaki, his father Hayao, and the other screenwriter Niwa had not injected melodrama and contrivance into their movie. That limits what could otherwise have been an excellent little mood piece. Nevertheless, what ended up on screen is still very good. The easy-going, winsome world of From Up on Poppy Hill is one well worth spending plenty of time in.

Leave a comment