In the next installment of my Zhang Yimou retrospective, I look at Ju Dou.

After his directorial debut of Red Sorghum, Zhang Yimou made a thriller, Codename Cougar (1989), which he co-directed with Yang Fengliang. Codename Cougar is not, as far as I can tell, available with English subtitles, so I have had to skip it in this series. (Should I ever discover an accessible version, I will fill in this gap later.)

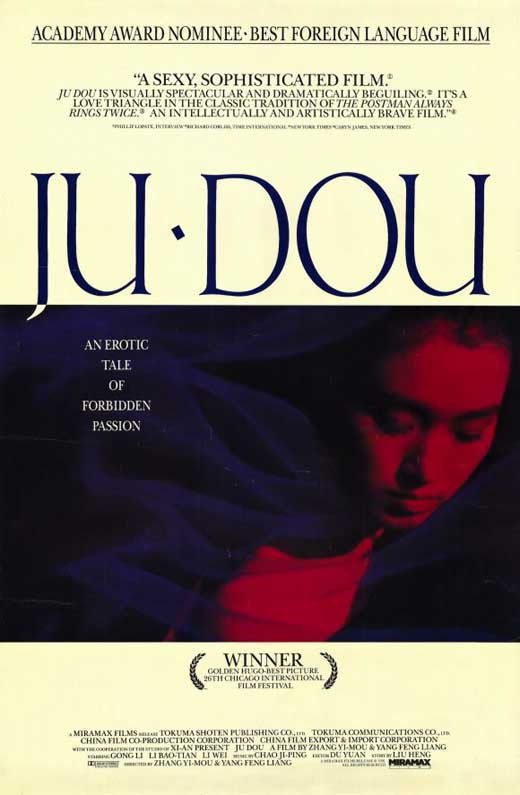

Moving on to Zhang’s next feature brings us to Ju Dou (1990). Ju Dou was also co-directed with Yang, from a screenplay by Liu Heng, who adapted the script from his own novella. The movie received much international attention, being nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film—the first Chinese film ever to receive this distinction.

In my review of Red Sorghum, I described that movie as “rough.” Watching Ju Dou, I felt that I was now seeing the more confident, polished movie for which Red Sorghum was the rough draft.

The two movies have similar stories. Both are set in rural China during the early 20th century. In both, a beautiful young woman, played by Gong Li, is unwillingly married to an older, relatively wealthy man. Dissatisfied with her life, she begins an affair with a younger man. The lovers find some happiness, but circumstances ultimately work against them.

Ju Dou (Gong) is the third wife of Jinshan (Li Wei), who owns a cloth-dyeing mill in a small village. Jinshan is a cruel tyrant who physically and emotionally abuses Ju Dou (the movie implies his first two wives died as a result of similar ill treatment). Witnessing this unjust situation is Tianqing (Li Baotian), Jinshan’s nephew and chief helper in the mill.

Tianqing pities and desires Ju Dou. She returns his feelings and the two secretly begin a relationship. Complications arise when Ju Dou becomes pregnant. Then a dramatic turn of events seems to help the lovers. Escaping their unhappy domestic trap proves harder than one might expect, though.

I don’t know precisely how filmmaking responsibilities were divided between Zhang and Yang, but many of the same approaches to visuals as in Red Sorghum are present here. Part of the credit for this common approach may go to Gu Changwei, the cinematographer on Red Sorghum who also photographed Ju Dou along with Yang Lun.

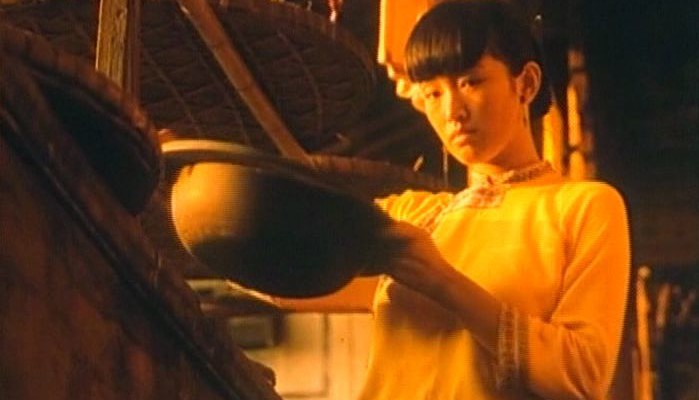

In Ju Dou, as in the earlier movie, we get striking uses of color (the movie was shot in Technicolor): the deep, hazy blue light that blankets nighttime scenes; the warm yellow sunlight in the upper levels of the dye mill and Jinshan’s house; the bold reds, blues, yellows, greens, and oranges of the cloth dyed in the mill. Characters in Ju Dou are frequently photographed as backlit silhouettes, as in Red Sorghum.

Ju Dou improves on its predecessor with tighter plotting. We don’t get any abrupt left turns in the story, as with the sudden arrival of Japanese invaders in Red Sorghum. The focus here remains on the tangled relationships of Ju Dou, Tianqing, and Jinshan, which play out fully to their logical conclusion.

The filmmakers also handle this drama with surprising subtlety. At first glance, this doesn’t seem like a story that would be told with much nuance. The clear villain here is Jinshan, who comes across as an inhuman monster who will stoop to pretty much any evil act to gain advantage or at least revenge for himself. Yet what is remarkable about the movie is how resolutely it refuses to reduce its story merely to a struggle against a single wicked man.

Multiple times in Ju Dou events seem to hurt Jinshan and help Ju Dou and Tianqing, but the lovers still cannot quite realize their hopes. One reason for these reversals is that Jinshan has custom and social expectations on his side. Even if he cannot directly stop Ju Dou and Tianqing from pursuing their relationship, the larger village society and its mores—personified by a rather mummified-looking group of village elders—can still thwart their happiness. Another, even more painful, reason for Ju Dou and Tianqing’s impossible situation is the behavior of the most seemingly innocent and blameless character in the movie.

These complexities of Liu’s screenplay highlight what Ju Dou is really about: the suffering caused both by a social system that gives men so much power over women and, even beyond that, by the simple unfairness of life. Such obstacles are much harder to overcome than one malevolent dye mill owner.

The filmmakers find an apt style for rendering this story. The movie has a deliberate pace and is punctuated by many brief shots of empty rooms or building exteriors that serve as little pauses in the narrative. Scenes generally play out in long or medium shots with minimal camera movement. Characters are often framed or partially obscured by some structure in the foreground: lattices, the mill’s machinery, tall grass, and the like.

This style accomplishes two goals. First, it creates a kind of detachment of the audience from the events on screen. We are watching this tragic story at a distance as it slowly but inevitably unfolds. Second, it captures the furtive, cautious feel of life in Jinshan’s household. We seem to be spying on the characters because that is what they are constantly doing to each other. (Early in the movie, for example, Tianqing tries to use a gap in a wall to watch Ju Dou undress.)

This second effect is reinforced by the overhearing and eavesdropping that recurs throughout Ju Dou. Both the characters and the viewers are constantly hearing dialogue or significant sounds from outside the rooms in which events are happening.

Zhang and Yang also show considerable canniness in how they stage scenes and how they introduce certain details only to return to them in a different context. The use of an axe at one point seems to foreshadow violence by one character that never occurs; however, the axe turns up again later to portend violence by another character that this time is realized. After the first time Tianqing tries to spy on Ju Dou undressing, she realizes what he has been doing. In a later scene, knowing Tianqing is watching, she proceeds to reveal herself to him—but in a way that is tragic rather than erotic.

Above all, some crucial scenes in the dye mill demonstrate the filmmakers’ skill. In one scene, something terrible befalls Jinshan. The obvious way to present this event would be as a satisfying comeuppance for the movie’s villain. However, the filmmakers avoid this approach and instead give the moment a ghastliness that inspires a kind of pity—if not for the character, then at least over the situation.

In another scene, Ju Dou and Tianqing consummate their relationship in the dye mill. The movie then cuts back and forth between the couple’s amours and the mill’s machinery: wheels and pulleys moving and creaking, cloth unraveling into a vat of red dye. When I first watched this, I thought Zhang and Yang had stumbled: the ham-fisted contrast of images seemed almost like how Monty Python might have staged such a scene. I misjudged the directors, though. This scene took on a new significance much later, when we get the same shots of machinery amid events that are not romantic but devastating. The second appearance of this imagery seems to mock Ju Dou and Tianqing’s earlier passion.

The memorable imagery continues all the way to the movie’s conclusion. In the final scene, Ju Dou takes drastic action. This occurs in a magnificent shot in which we first see the familiar image of the dye mill and its beautiful cloth before then seeing a new element enter the frame.

Ju Dou’s final choice is a dramatic one, but in this bleak tale it provides no final triumph or catharsis. Rather, it is simply an act of symbolic, despairing defiance.

Leave a comment