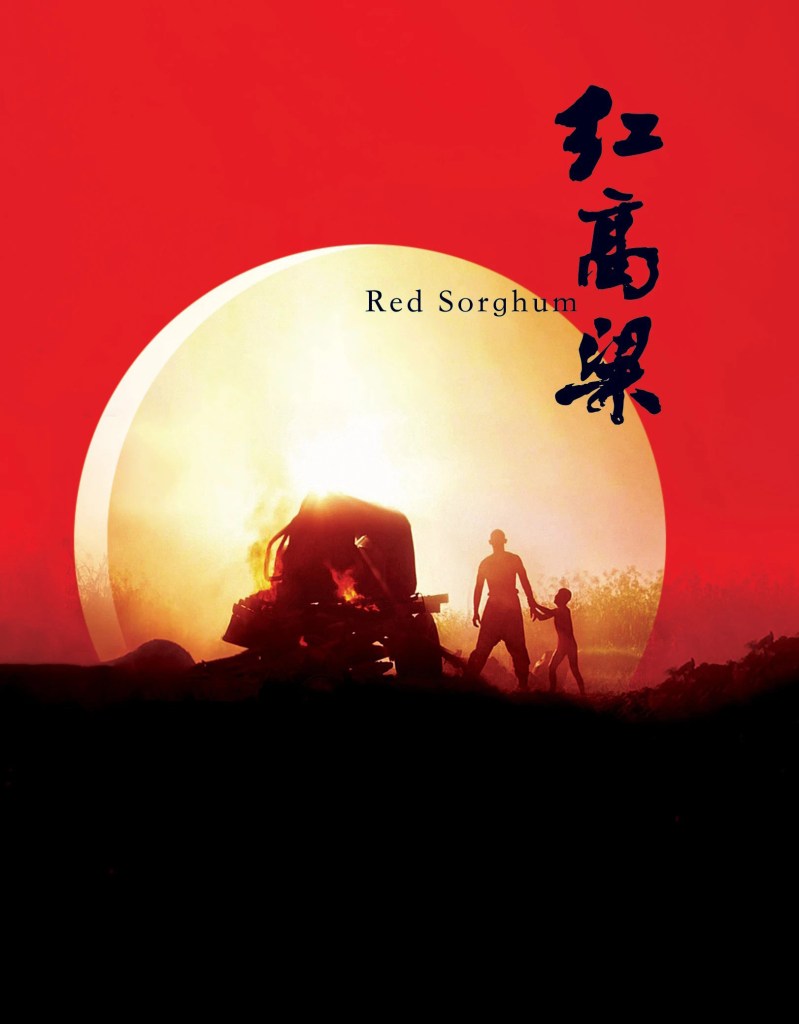

I kick off my next retrospective with a review of Red Sorghum.

As promised, I am starting a new movie retrospective series. This series looks at the films of Zhang Yimou.

Zhang is one of China’s most distinguished filmmakers. He is perhaps the most famous member of the first filmmaking cohort to attend the Beijing Film Academy following the end of the Cultural Revolution. Having worked as a cinematographer before he became a director, Zhang has frequently collaborated with actress Gong Li.

When I first encountered some of Zhang’s early movies, made circa the 1990s, I was very impressed. I neglected to follow his later work, though, and the time has finally come to correct this with the current retrospective.

However, I must make an admission at the outset: this retrospective will of necessity be incomplete. I cannot review all of Zhang Yimou’s movies simply because many of them are difficult to obtain on DVD or streaming and some are simply inaccessible, at least with English subtitles. (I make a plea to the Criterion Collection or some similar institution: release a complete, collectible set! Preferably at a discount!) I will do as complete a review of Zhang’s movies as I can, though, and will mention when I have to skip a title.

With that introduction out of the way, let’s look at Zhang’s directorial debut, Red Sorghum (1988).

Written by Chen Jianyu and Zhu Wei, and based on two novels by Mo Yan, Red Sorghum tells the story of a young woman (played by Gong) in a rural community in 1930s-era China. Known as Jiu’er, the woman is the ninth child in her poor family, and to improve the family’s fortunes she is married off to a local winemaker. However, the winemaker is much older than Jiu’er and has leprosy, which makes her averse to the match. She takes a greater interest in a strapping younger man in the community (Jiang Wen, probably best known to western viewers as Baze Malbus in Rogue One), who nevertheless has his own problems.

Events lead to Jiu’er having to manage the winery herself, making a distinctive wine from the wild red sorghum that grows in the area. She also tries to manage her relationship with the younger romantic interest. Meanwhile, the threat of World War II and the Japanese invasion of China comes to affect these characters and their community.

The movie is narrated by Jiu’er’s grandson, who is recounting all these events from some point in the future. From his voiceovers, we learn that Jiu’er’s romantic interest is his grandfather (and that’s not a spoiler: this information is revealed in the movie’s first five minutes).

If I had to characterize Red Sorghum in one word it would be “rough.” The movie’s characterization and plotting presented problems for me. The characterization issues seem to be entirely intentional, so I cannot quite consider them “flaws”; they did limit my enjoyment of the movie, though. The plotting issues, however, I think are just signs that screenwriters Chen and Zhu should have put the script through some more rounds of revision. More important, Red Sorghum is also “rough” in the sense of telling a story that is harsh, earthy, and at times very disturbing.

Still, screenplay issues aside, Zhang and cinematographer Gu Changwei still created a highly visually impressive movie. Red Sorghum is great to look at; the use of color in particular is striking. You can see great talent and potential here, even if this specific movie has its limitations.

The biggest obstacle in appreciating the movie is the character of Jiu’er’s romantic interest—who, as far as I can tell, is never named in the movie; the narrator simply refers to him as “Grandfather.” The character comes across as a nasty piece of work. He is prone to drinking, violence, and making scenes. The last tendency creates multiple confrontations with Jiu’er, including a scene where the Grandfather wreaks havoc with the winery. Also, he doesn’t appear to be that interested in consent. Multiple times he simply picks up Jiu’er and carries her off, caveman-style, to a tryst. We’re meant to understand that she welcomes his advances, yet he doesn’t seem concerned with asking permission beforehand.

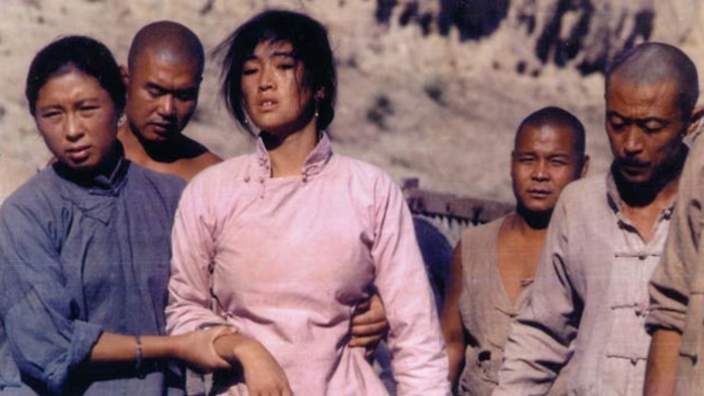

Why does Jiu’er put up with this rat? The answer largely seems to be raw sexual attraction. This is conveyed effectively in a brief but memorable shot where Gong Li, just through her eyes and a few subtle facial changes, reveals her interest in the Grandfather. Her attitude is also somewhat explicable given that, within the limited options of their rural community, the Grandfather character is preferable to her than a leprous older man.

All this makes sense as far as it goes, but as a result I found both of Red Sorghum’s central characters hard to relate to. Granted, I didn’t get the sense the filmmakers had illusions about their characters. We aren’t meant to think the Grandfather is a lovable person. The movie presents these events simply and straightforwardly, a perspective reinforced by how the story is told in retrospect by the characters’ grandson. The narrator is recounting some family lore, with a “that’s just the way it happened” attitude.

While this story-telling approach is a valid choice, it combines with the unappealing nature of the Grandfather and the fact that none of the central characters change much during the movie to make Red Sorghum rather emotionally distant. I didn’t feel as much while watching as perhaps I was supposed to.

Also, as I mentioned, some of the plotting seems outright sloppy. The threat from the invading Japanese emerges quite abruptly in the final half hour of this only 90-minute movie. Further, some tragic events at the climax left me puzzled as to why characters made the choices they did. The final tragedy seems to be the result of poor planning, although I am uncertain of whether this was poor planning by the characters or the filmmakers (I suspect the latter).

OK, enough negativity. What works in Red Sorghum?

For starters, the color. Zhang and Gu use bold, brilliant colors: the red of clothes, curtains, the wine, and blood; the sandy-yellow of the desert-like countryside; the green of the sorghum fields; the misty blue of the nighttime. These vivid colors are contrasted nicely.

An early scene of the betrothed Jiu’er being carried, by the Grandfather and others, in a sedan chair to the winemaker’s home gives us the striking image of the crimson sedan chair against the yellow land. The scene’s imagery also gives us a nice illustration of the underlying situation. Confined within the chair, Jiu’er looks stifled amid the oven-like red light, while the men outside march and dance along in the freedom of the open air.

Zhang shoots scenes in interesting ways, as well. I appreciated how he let scenes with multiple people play out in medium or long shots, with minimal cutting. This approach of letting the actors’ movement and the underlying drama provide the action, rather than underlining moments with edits or close-ups, makes the scenes more absorbing, even suspenseful. The approach seems to tell the viewer, “Watch closely; let’s see what happens.” This works particularly well in the scene where the Grandfather disrupts the winery.

We get a number of memorable tableaux. The workers at the winery gather for a brief ceremony, which is both solemn and playful, in which they pay tribute to the god of wine for the fruits of their labors. Later, the same ceremony is repeated in a far graver context.

Characters are sometimes depicted in silhouette against light sources. And, in perhaps the movie’s most indelible image and striking use of color contrast, a distraught, blood-soaked man appears before a background of green sorghum.

In general, the wild sorghum fields—which, the narrator tells us, are reputed to be haunted—are used well. The green plants suggest life and fertility, but Zhang and Gu frequently depict the fields in a washed-out, dusk-like light that, combined with the wind whipping through the sorghum, gives the fields an ominous atmosphere. Hence, many scenes of danger or violence play out in the fields: an early encounter with a bandit; the Grandfather chasing Jiu’er; the Japanese mistreating the Chinese villagers; and the final climactic events.

Red Sorghum also sometimes displays impressive storytelling economy, making certain points effectively with a minimum of a fuss. The movie opens with a few quick shots of a rather catatonic-looking Jui’er being dressed and done up in preparation for her marriage to the winemaker. Her initial status as a mere object who is handed along by others is thus rapidly and forcefully shown.

Later, in what is easily the movie’s most agonizing scene, the Japanese soldiers’ brutality toward the Chinese is demonstrated. This is accomplished not through graphic violence but by just an especially macabre idea illustrated by a few carefully selected images.

Also, while the Grandfather is a creep and Jui’er somewhat opaque, other characters are more successful. My favorite is Brother Luohan (Teng Rujun), the wizened manager of the winery. Teng exudes competence and decency in the role. The other winery workers don’t emerge as distinct characters but they have memorable faces and are likable. (If the movie had been purely about Jui’er running the winery and presiding over her household community, I think I would have enjoyed the movie far more.)

Other characters who make an impression are Sanpao (Ji Chunhua), a bandit chieftain, and a couple of weaselly butchers who work for him. The trio are scoundrels who become sympathetic when they receive their all-too-apt comeuppance.

Overall, I don’t think Red Sorghum quite works. The central characters are too distant and the plot a bit too patched together. Still, it’s an impressive first effort from Zhang. Desson Howe put it nicely in his review: “It’s almost comforting that ‘Sorghum’ has structural shortcomings — if Yimou’s debut were any better, he’d have to be tested for artistic steroids.” In future months, we shall see what future heights he reached.

Leave a comment