Next in my Studio Ghibli retrospective, I turn to the not-quite-beloved Tales from Earthsea.

Back in the 1980s, Peter Hyams wrote and directed a sequel to Stanley Kubrick’s classic 2001: A Space Odyssey. Titled 2010: The Year We Make Contact, the sequel provided a follow-up to the basic events of the original movie but was otherwise completely different stylistically and tonally. In place of Kubrick’s cold, hypnotic, and visually stunning masterpiece, which explained little and had a famously ambiguous ending, Hyams provided a conventional sci-fi adventure movie, with relatable characters and an on-the-nose, humanistic message.

Needless to say, reaction to 2010 has been mixed. The movie inevitably suffers in comparison to its incomparable predecessor. And, to be sure, 2010 is nowhere near as good or as creative as 2001. Taken on its own terms, though, it is a pretty good movie. As Roger Ebert wrote at the time, “[O]nce we have freed 2010 of the comparisons with Kubrick’s masterpiece, what we are left with is a good-looking, sharp-edged, entertaining, exciting space opera — a superior film of the Star Trek genre.”

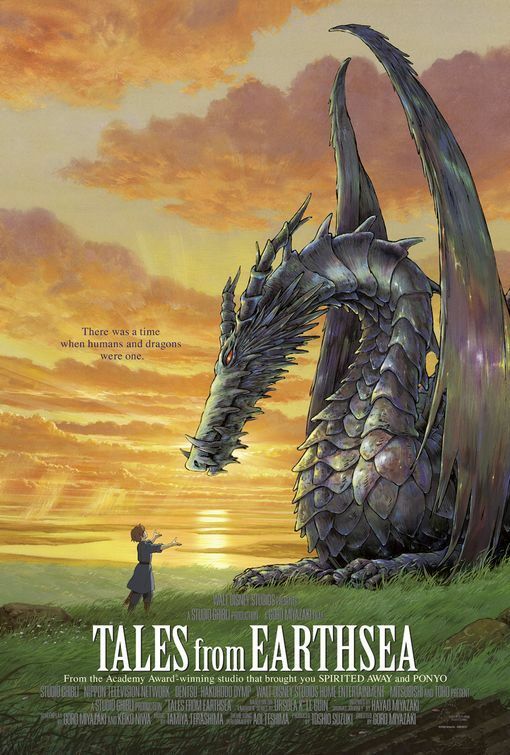

I provide this little digression on cinema history because I was reminded of the 2001/2010 rivalry when watching Tales from Earthsea (2006), written and directed by Goro Miyazaki. Among Studio Ghibli movies, Tales from Earthsea has the dubious distinction of being renowned as “the bad one,” the rare creative misfire from the otherwise reliable Ghibli team. The movie routinely turns up at or near the bottom of rankings of the Ghibli canon.

I can understand why the movie received this reaction. It’s certainly flawed and it’s not much like most other Ghibli movies, including those directed by Goro’s father, the studio’s co-founder Hayao Miyazaki. Tales from Earthsea lacks the riot of inventive world-building and character design, the whimsy and playfulness, and some of the complexity of many other Ghibli movies. (The movie probably also suffers in comparison to the Ursula K. LeGuin books it is based on, but as I haven’t read the books I cannot comment on that.)

Yet, taken purely on its own terms, I found Tales from Earthsea to be a decent movie. It’s no Princess Mononoke or Spirited Away, but it’s a solid, absorbing fantasy adventure. In a couple respects, it even improves on other Ghibli work by boasting better pacing and a more rousing climax than many of the elder Miyazaki’s movies. As the 2010 to other Ghibli movies’ 2001, the movie deserves more appreciation than it typically receives.

The movie opens with the Kingdom of Enlad in turmoil. Crops are failing, pestilence is breaking out, and rare sightings of dragons portend further misfortune. Meanwhile, the witches and wizards who aid Enlad in various ways seem to be gradually losing their magical abilities.

Truly the time is out of joint—yet it’s not the kingdom’s prince who is going to set it right. Instead, in a shocking early twist, Enlad’s king is killed by his own son, Prince Arren. Precisely why Arren does this is never fully explained in the movie, but much of Tales from Earthsea revolves around the teenage prince’s profound emotional torment. Arren steals his father’s magical sword and, driven by his demons, flees the kingdom for other lands.

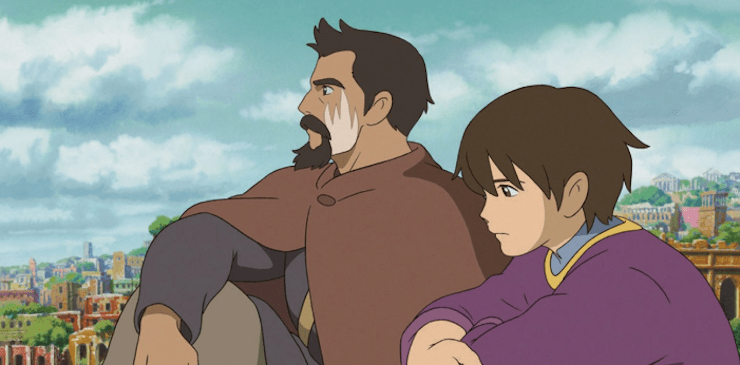

In his wanderings, Arren meets Sparrowhawk, a wizard who becomes a protector to the disturbed young man. They eventually find refuge at the farm of Tenar, a witch with whom Sparrowhawk has a history. Also living at the farm is Therru, an emotionally and physically scarred orphan girl whom Arren saves from slave traders at one point. She is slow to warm to him, though, as she senses his troubled nature.

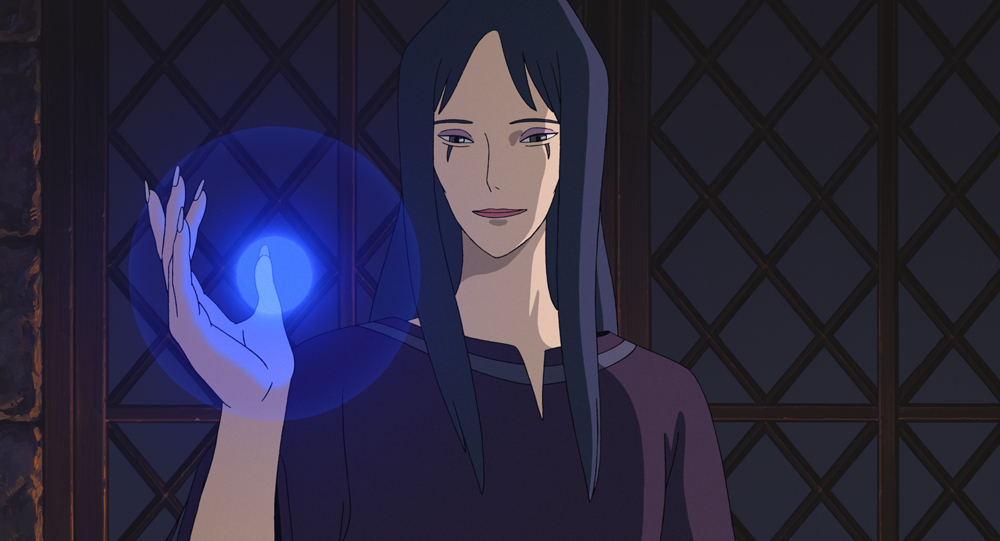

The improvised family of four live and work on the farm and enjoy something like a normal life for a time. After Therru’s initial hostility fades, she and Arren begin to form a relationship. Yet life on the farm is threatened both by Arren’s inner turmoil and the machinations of the evil Lord Cob. Cob, a rival wizard to Sparrowhawk, seeks immortality and is apparently the force behind Enlad’s many troubles. All these conflicts and dangers come to a head as our protagonists must face off against Cob in his fortress lair.

As I mentioned, I understand why many critics and Ghibli fans don’t like this movie. In contrast to the often quirky and surprising stories featured in other Ghibli movies, Tales from Earthsea follows broadly familiar fantasy tropes. We have the young protagonist on a journey, the mentor figure, the villain, and the climactic battle. The magical sword Arren steals and carries with him for much of the movie carries echoes of Excalibur and (more relevantly) the sword Dyrnwyn in Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain. Meanwhile, anyone familiar with the career of Lord Voldemort will not be surprised by Cob’s character or motivations.

However, while these tropes might not be original, they aren’t inherently bad. Goro Miyazaki tells this well-worn story effectively and does a good job with the characterization of Arren. I appreciated how the prince gradually changes from anti-hero to hero. Although the movie ultimately softens the horror of his initial murder of his father by revealing him to have been possessed by some madness and out of his right mind, he still has serious flaws that he must outgrow (and he must still face the consequences of his crime).

Arren is paralyzed by his fear of death—an apt parallel to Cob’s concerns—and flees his old life, human ties, and even his grasp on reality to avoid facing up to this fear. He is divided against himself, a conceit the movie portrays by showing us his nightmares and his recurring vision of a strange doppelganger figure. The identity of this figure, when we finally learn it, provides a nice little twist to the story.

We also get some interesting situations early in the movie, when Arren’s half-crazed state makes him paradoxically braver in the face of danger. I liked the scene where Arren helps Therru escape the slave traders and must improvise a reckless, desperate defense against the attackers.

Arren and Therru’s relationship is also handled well. Therru recognizes the despair behind Arren’s apparent courage and keeps her distance. Yet the two connect in an absolutely lovely scene, the best in the movie, when Arren goes looking for Therru at dusk and finds her in a field singing a lament about her loneliness. Miyazaki doesn’t rush but just lets the moment play out, as Therru sings and Arren watches her and realizes he sees a kindred spirit. It’s a beautiful scene.

After that, Arren confides in Therru about his crime and his inner torment, and she begins to care about him. This prompts her to take risks on his behalf and finally leads to a crucial turning point in which Therru helps Arren overcome his demons.

The movie’s villain, Cob, is hardly a subtly drawn character, being one of the few purely evil characters in Ghibli movies. Yet Cob is very effectively scary, being powerful and cunning and having a memorably cadaverous character design. The character even benefits from one of the odder choices by the English dub’s creators. As far as I can tell, the character in the Japanese original was meant to be a woman: Cob looks feminine and was voiced by a Japanese actress. I don’t know why the gender swap was made, but the incongruity of a man’s voice coming out of a woman’s body only adds to the character’s unsettling quality.

The movie has a well-crafted climax. As Patrick Willems has pointed out (in turn citing Michael Arndt), the most satisfying movie climaxes are those that simultaneously resolve the story’s external, internal, and philosophical/thematic conflicts. Tales from Earthsea does that, in a finale that brings together the external threat from Cob, Arren’s internal struggles, and the movie’s theme of how death is an inevitable part of life and we must accept death if we are truly to embrace life. While the climax can perhaps be faulted for relying on a deus ex machina moment involving an unexplained aspect of Therru’s character, I didn’t care—the ending still feels like a worthy, cathartic payoff.

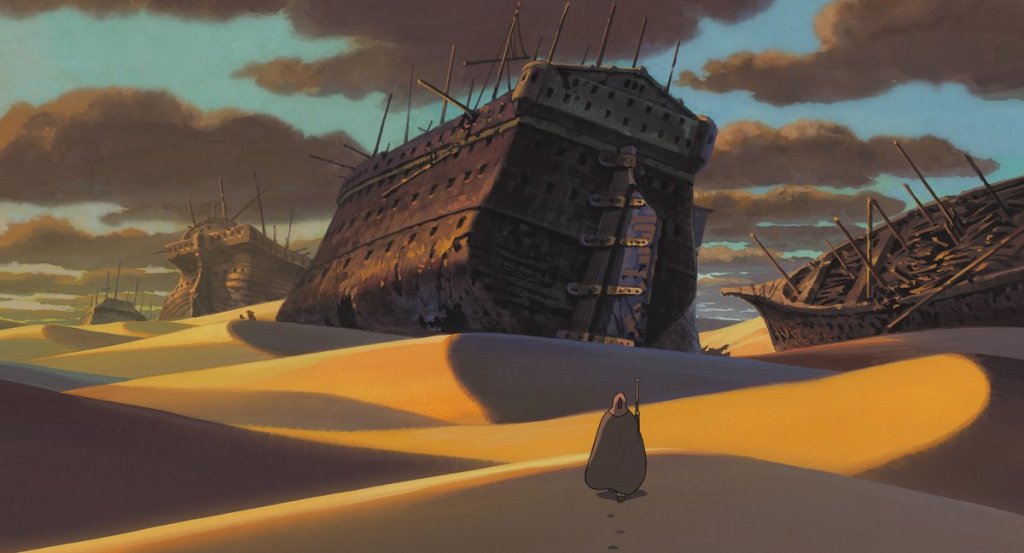

If an aspect of the movie disappointed me, it was the rather ho-hum visuals. While nothing in Tales from Earthsea looks outright bad, the movie didn’t look especially good, either. I expect a lot from a Studio Ghibli movie’s animation and this movie was underwhelming in that regard.

We get a few memorable locations. Sparrowhawk briefly wanders through a desert marked by the eerie, inexplicable presence of wrecked ships’ remains.

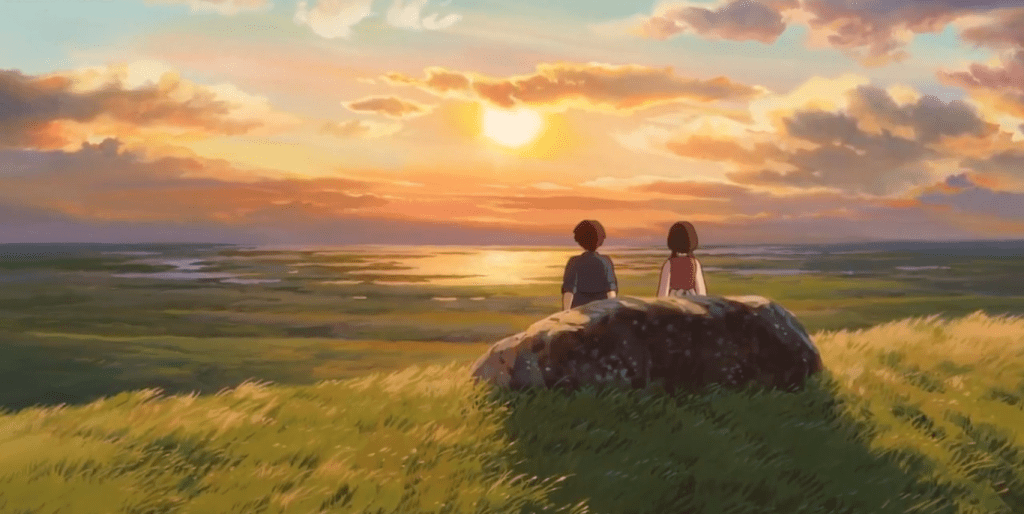

The green countryside around Tenar’s farm is bucolically beautiful. Yet the movie shows us little of the exotic, grotesque, or magical imagery that make Ghibli movies special. Cob’s fortress, for example, is just a Generic Fairy Tale Villain’s Castle.

The exception to the unimpressive visuals is the rendering of the sky. We get numerous memorable skylines, at various times of day and night, both in reality and in Arren’s dreams. The sunrise in particular is used to spectacular effect at the movie’s climax.

The English dub is a mixed bag. Matt Levin (as Arren), Blaire Restaneo (as Therru), and Mariska Hargitay (as Tenar) all do effective, if somewhat bland, voice work. The standout is Willem Dafoe as Cob. Dafoe’s distinctive flat, “dead” voice is perfectly suited to the villain and his choice to deliver all his lines in a near-whisper makes Cob all the creepier. The big disappointment of the voice cast is Timothy Dalton as Sparrowhawk. Dalton has one of the great voices in cinema, yet his performance is so relentlessly Grave and Serious as to become a bit boring. (Still, hearing Dalton and Dafoe play a confrontation makes me wish for a James Bond movie we never got.)

The movie’s best image comes after Arren watches Therru sing. We then see the two of them sitting together watching the sunset, framed by the gorgeous sky and green landscape.

Tales from Earthsea doesn’t have many humanizing details—that’s another of the ways it doesn’t feel very “Ghibli.” Still, I did notice one such detail. When Sparrowhawk and Tenar are talking in a scene, Sparrowhawk finishes some stew Tenar has served him and then takes a moment to rinse out the bowl with water. It’s good to know even powerful wizards clean up after themselves.

In the end, I would pronounce Tales from Earthsea a competently made adventure movie with some good characters and a strong ending. It’s not much like Studio Ghibli’s usual work, and both the studio and Goro Miyazaki specifically have done better work. Yet it doesn’t deserve its bad reputation, and I suspect the movie wouldn’t have such a reputation if it were viewed outside the shadow of other Ghibli movies.

Leave a comment