Having been recommended the movie by a friend, I recently watched The King of Masks. Here’s the review!

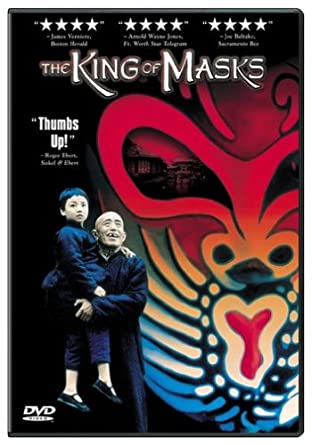

The King of Masks (1996), directed by Wu Tianming from a screenplay by Chen Wengui, introduces us to Wang, an older man who makes a living as a wandering street performer in China’s Sichuan province in the 1930s. In the various towns he travels through, Wang provides displays of bian lian, or “face changing.”

A technique of Sichuan opera, face changing involves a performer wearing a variety of brightly colored, intricately decorated silk masks meant to reflect characters’ various emotions. What is remarkable about the technique is how face changing performers can rapidly speed through mask changes, so their masks switch in the blink of an eye. The skill resembles juggling or a magic trick in how it deftly pulls off the seemingly impossible.

An opera company of one, Wang demonstrates his face changing skills, tells stories, and otherwise entertains people. He just barely makes a humble living, his few possessions all residing on a boat that gets him from place to place by river and serves as a makeshift home. Wang’s sole companion is a performing monkey named “General.” He has no family, his only son having died many years ago.

The lack of an heir presents a professional problem for Wang, as the skill of face changing is meant to be passed down from father to son within families—and is strictly off limits to women or outsiders. Rather than accept that his skills will die with him, Wang seeks to adopt a child by going to what appears to be a town’s informal bazaar where poor families sell their children (a disturbing detail the movie presents matter-of-factly and doesn’t linger over). In the bazaar, Wang meets a sweet-faced, affectionate child whom he adopts and names “Doggie.”

Wang’s dreams seem to have come true, and he lavishes attention and care on his new “grandson.” The dream is soon shattered, however, when [SPOILER ALERT] it becomes apparent that Doggie is actually a girl who had been dressed up as a boy, presumably to make her a more appealing purchase in the bazaar. Bitterly disappointed, Wang grudgingly keeps her on as an assistant but won’t teach her face changing. Grateful for any kind of family life, Doggie works faithfully for Wang and hopes to be accepted.

In its broad outlines, The King of Masks is a familiar story. Anyone who has ever seen a movie about (1) a curmudgeonly old man who must take care of a child or (2) a girl striving to prove herself in a field that favors boys will probably be able to predict the basic story beats and ultimate resolution. Nevertheless, Wu, Chen, and the rest of the filmmaking team tell their tale with great deftness—rather like a face-changing artist.

I appreciated the portrayals of our central characters, Wang and Doggie, played by Zhu Xu and Zhou Renying, respectively. Both are likable, but the movie avoids the cloying trap of making either of them too nice. Wang is a basically decent man who is capable of kindness, and his poverty and loneliness invite our sympathy. Nevertheless, Wang also drinks, curses freely, and more than once treats Doggie poorly.

Doggie, as an innocent orphan just struggling to survive, naturally invites even more audience sympathy. She also shows resourcefulness and great bravery in moments of crisis. At the same time, she manages to be quite a handful: she talks back to Wang, steals from a shop, and (unintentionally) brings huge amounts of trouble down on Wang’s head more than once. She may be a heroine, but she’s not an angel. I especially liked the detail that when ordered by Wang to return the item stolen from the shop, she doesn’t virtuously confess all to the shopkeeper but simply takes advantage of his distraction to put the item back unnoticed.

Both actors get some nice bits of business that add texture to their characters. In one scene on the boat, Wang makes use of a back-scratching tool only to discover that Doggie can do a better job of scratching his back. As he contentedly settles into this new arrangement, Wang pauses to throw the back-scratching tool overboard. When the two of them get their photograph taken, I liked the touch of Doggie’s reflexive flinching at the camera’s flash. Also, credit must go to the young Zhou for doing some quite extraordinary gymnastic contortions as part of the duo’s street act.

Alas, the movie’s general avoidance of cutesiness does not apply to General, the performing monkey. As employed here, General is only a spoken line or two away from being a sidekick in a Disney movie. Wu and company even stoop to using that old comedic chestnut, the Animal Reaction Shot.

Along with the characterizations, I appreciated the careful way the filmmakers set up various aspects of the plot, as well as other significant details, and how these elements fell into place later. For example, early in the movie, we are introduced to a child (not Doggie) who turns up again at other crucial points in the movie and plays an important role in the final act. Wang repeatedly crosses paths with a Sichuan opera star whose specialty is female impersonation. This opera star not only plays a pivotal plot role in the movie but foreshadows Doggie’s imposture and provides a kind of mirror image of the girl. Further, an opera performance midway through the movie, a version of the story of Miao-shan, sets up the movie’s climax.

The movie also includes some lovely visuals. A beautifully composed shot of Wang sitting on his boat while Doggie scratches his back captures a warm domestic feeling. Later, after disaster has befallen him, we get a powerful shot of Wang mutely contemplating what has happened.

The filmmakers also use color to good effect. As portrayed here, Sichuan is a permanently overcast and misty world of muddy waters and muddy streets. Blues, grays, and browns dominate, especially during the earlier parts of the movie. This gives The King of Masks a rather drab look overall, but it makes the appearance of brighter colors all the more striking. The various opera performances inject memorable pageantry into the movie. Wang walking down the street with an orange umbrella similarly makes for a nice image.

When Doggie is revealed as a girl, she swaps her blue boy’s jacket for a vivid red jacket. We then get a marvelous shot of her, in red, sitting on the boat framed by the dark river waters. The use of color is not merely visually striking but resonates on a larger story level. The changing colors signal both a change in the plot’s direction and the arrival of a vital new presence: Doggie as she truly is.

If I had to offer a significant criticism, which applies both to the movie’s storytelling and its visual sense, it is that Wang’s face-changing performances receive surprisingly little screen time. We see some snippets here and there of him changing masks, and the sight is certainly an impressive one. We never get much more than snippets, though. We never get to see a full, sustained performance, which is a shame. The King of Masks deserved better than that.

In closing, I will note that reviewing this movie fortuitously provides a nice segue into my plans for future reviews. Suffice it to say, we will soon be visiting the Middle Kingdom again. Stay tuned…