Next in my Studio Ghibli retrospective comes Howl’s Moving Castle.

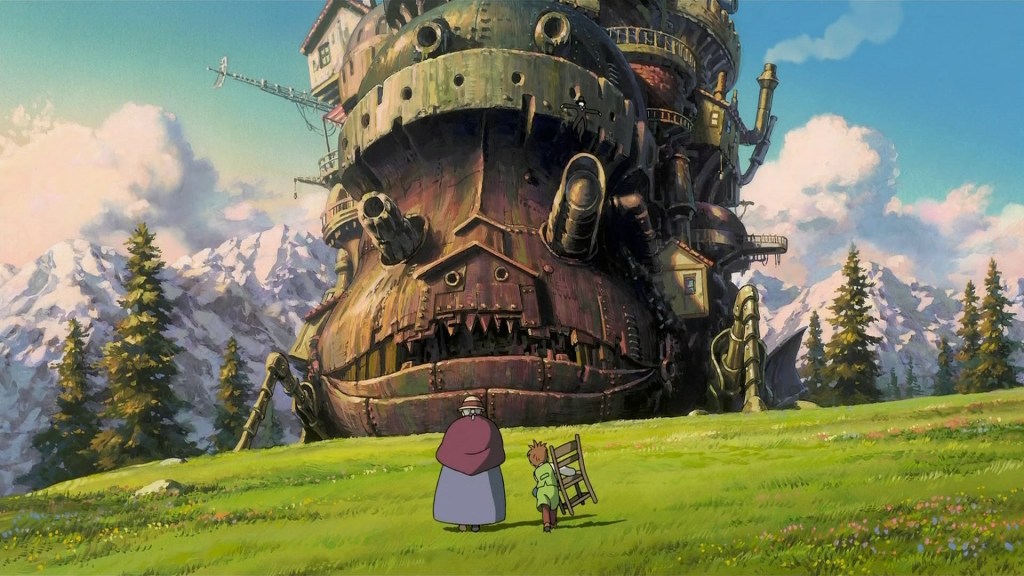

Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki, boasts perhaps the most memorable opening shot of any Ghibli movie. We open with a near-blank screen, as the frame is filled with fog that shrouds the landscape. Through the mist, the silhouette of some vast figure becomes visible as it gradually moves toward us. Then, with an array of clanking and whirring, the titular castle moves into view.

The castle is a fantastic contraption, a hodge-podge of architecture and machinery containing smokestacks, cranes, domes, telescopes (or are they cannons?), and several complete houses all slapped together into one grotesque whole. Many of these disjointed pieces look rusted or worn, as if they are wreckage from older buildings. The castle moves by scuttling along on two tiny, bird-like mechanical legs that improbably support the vast structure above. The legs, combined with two eye-like telescopes and a mechanical maw at the castle’s front, make the castle look like a living creature. Having been introduced to the castle, we then watch it creep along a green, mountainous landscape, dwarfing a shepherd and flock below it.

The castle’s introduction provides not only a magnificent opening image but a kind of summation of the movie to follow. Like the structure it’s named after, the movie Howl’s Moving Castle is inventive and visually stunning yet also more than a little clunky and unwieldy. Both manage to hold together, though, and convey, through all their mechanics, something vital and, well, moving.

The movie, based on a book by Diana Wynne Jones, takes place in a fantasy realm vaguely reminiscent of a Central European kingdom circa the late 19th century. In this kingdom, magic, witches, and wizards exist and are taken for granted by everyone. Some wizards have even set up shops in towns and cities and hire out their magical services to locals. Among the land’s wizards is the mysterious Howl, who lives in the moving castle. Howl has a reputation for preying on beautiful women and “eating their hearts” (the movie deliberately blurs the line between romantic enchantment in the magical and more conventional senses). Meanwhile, war brews between the kingdom and another land.

Trying to make her way amid this world of magical and political dangers is our young heroine, Sophie. She works in her family’s hat-making business but lacks a clear direction in life. She also labors under a burden of personal insecurity, as she is less conventionally good-looking than her sister, who has an array of admirers.

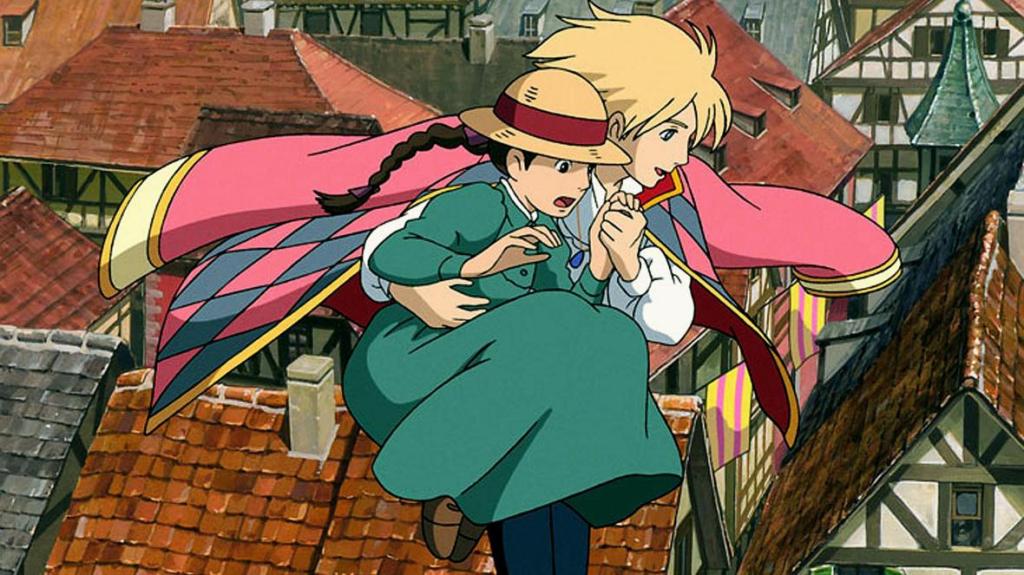

In an early scene, Sophie’s life takes a dramatic new turn when she is harassed by some aggressive soldiers only to be rescued by none other than Howl, who is on the run from his own pursuers. Howl gets Sophie to safety by taking her, much to her astonishment, on an aerial walk across the city.

However, her encounter with Howl carries a high price. Howl is being pursued by the malevolent Witch of the Waste, who has an ax to grind with him, and the Witch now directs her hostility to Sophie. The Witch turns up in the hat shop one night and curses Sophie, transforming her into an elderly woman.

Unable to face her family and not knowing what else to do, the newly aged Sophie makes her way to the countryside where Howl lives. Guided by a magical scarecrow she dubs “Turnip Head,” Sophie finds the castle and meets its various residents. In addition to Howl, the moving castle houses a young boy named Markl, who acts as a gopher for the wizard. Also, there is a “fire demon” named Calcifer, a kind of sentient flame who lives in the castle’s stove and serves as the castle’s main power source (although the movie doesn’t quite spell it out, I gather the castle is run by steam power, with Calcifer presumably heating the water).

Calcifer and Howl are bound together magically, a situation Calcifer desperately wishes to escape from. Sophie becomes intrigued by this magical bond and tries to learn more about it. Unlocking its secret might offer a path for her to break her own curse and return to her original, youthful form. As she tries to find a solution to her condition, Sophie stays in the castle and works as housekeeper for this shambling, untidy home.

If all this sounds rather complicated, believe me when I say you don’t know the half of it. This movie has a lot of plot, which I won’t attempt to summarize in full—for one thing, I am sure I didn’t understand all of it. This over-complicated plotting is one of Howl’s Moving Castle’s biggest weaknesses. I wasn’t always sure what the significance of certain events was, a problem aggravated by Miyazaki’s problems with pacing. The movie lingers on slower, quieter moments but rushes through more action-heavy ones, which sometimes left me confused. When we do eventually learn more about Calcifer and Howl’s magical history together, I can’t say I understood what it meant.

The movie has another big weakness, which I will get to shortly, but I first want to talk about some of the movie’s strengths. First, we have the visuals. I know that saying a Ghibli movie looks good is like declaring water is wet, but this movie in particular looks really, really good. The countryside, with its green fields dotted by lakes and its alpine mountain ranges, is among the most gorgeous natural settings in a Miyazaki movie. Further, the landscape is stunning even when far from pretty: a scene where Sophie and Turnip Head travel through the country at dusk features a powerfully ominous combination of dark storm clouds and a blood-red sunset.

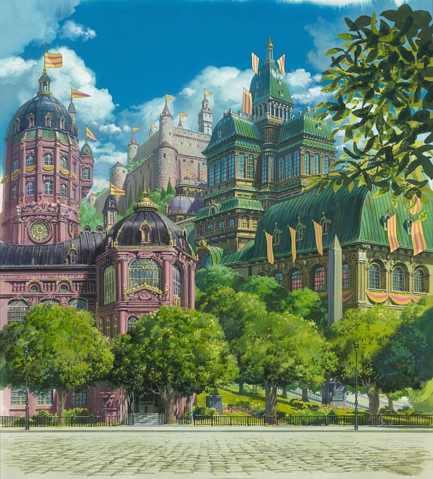

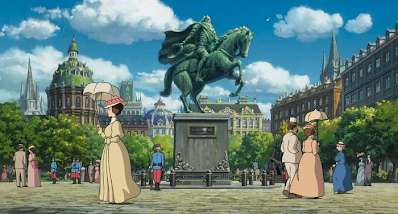

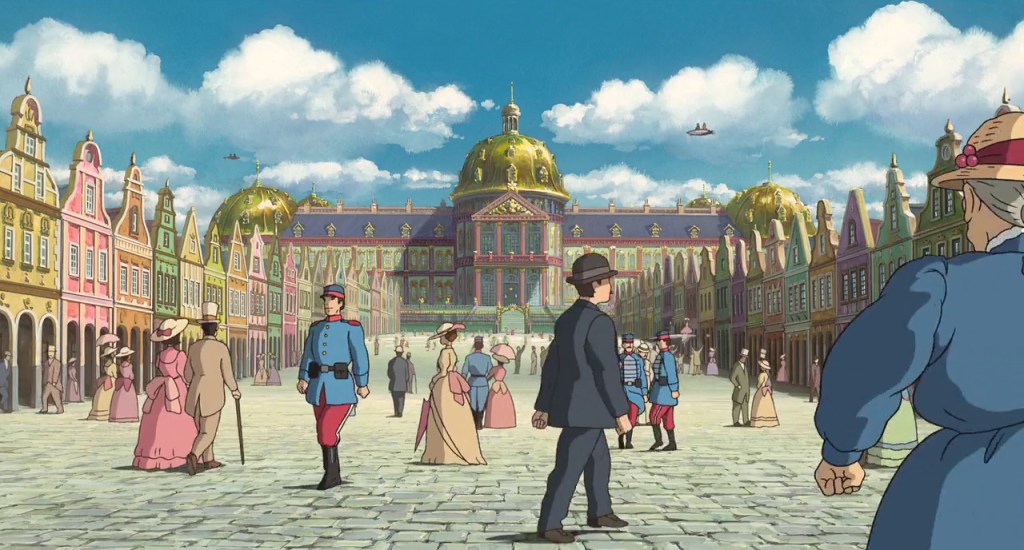

The more urban locations are animated no less impressively. Both the kingdom’s capital city and the smaller towns are all Old World elegance, filled with ornate edifices, quaint wooden buildings, and teeming city squares. It’s like everyone’s dream vacation to Vienna or Paris realized on screen.

The king’s palace is especially impressive, and I liked the palace’s vast greenhouse, with its contrasting polished marbled floor and abundant vegetation.

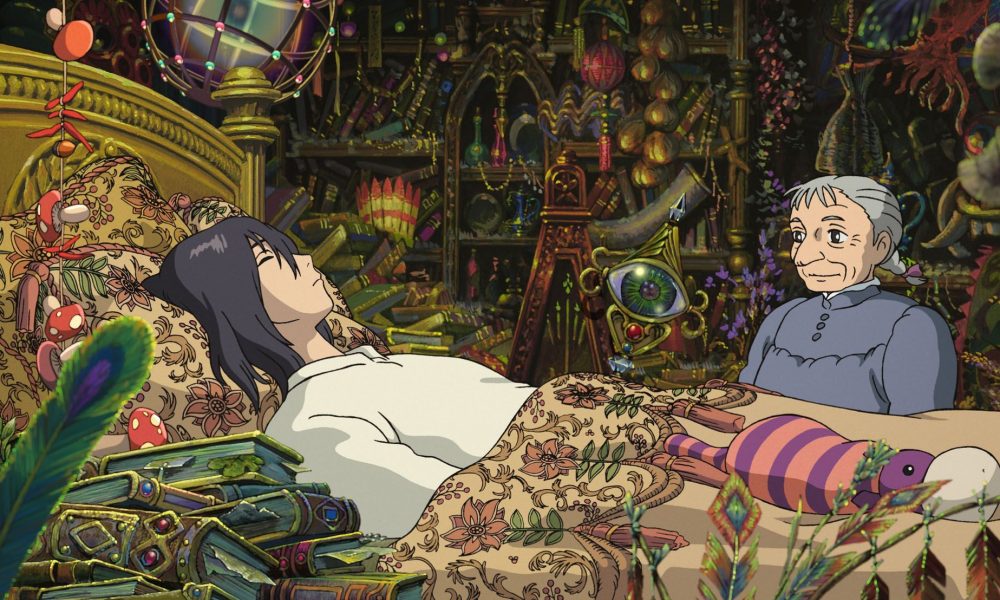

Howl’s room in the moving castle presents a different kind of spectacle, every inch being crammed with every kind of baroque gadget, knick-knack, or bauble you can imagine.

Again, it’s trite to say Ghibli shots are painterly, but Miyazaki and his animators have filled Howl’s Moving Castle with beautifully composed shots that do look as if they are paintings.

Character design is also well done. Howl looks the perfect picture of the charming rake, being tall and delicately lanky, with pale blue eyes and flowing blond tresses (which change to black later in the movie but remain no less impressive).

However, he can magically change into a more sinister form: a kind of half-human, half-bird creature. Howl takes this form to fight in the war that eventually breaks out, and we get a memorably creepy shot of him returning from the battlefield late one night and collapsing into a chair in exhaustion.

The Witch of the Waste is a towering woman decked out in furs and a massive hat who resembles a kind of demonic Margaret Dumont. She looks frightening in her early scenes but is later cursed in a similar way to Sophie and becomes smaller and frailer.

Sophie is drawn in perhaps the most subtle way. Early in the movie, she goes through a big change from a young woman to an elderly woman, but her character design then goes through innumerable small or brief fluctuations between younger and older—an important visual cue that something more than an external curse is affecting her condition. Also, we get one indelible and hilarious shot when the elderly Sophie is livid with rage and, as the animators toss aside subtlety for a moment, her face goes through perhaps the most extraordinary contortions ever committed to film.

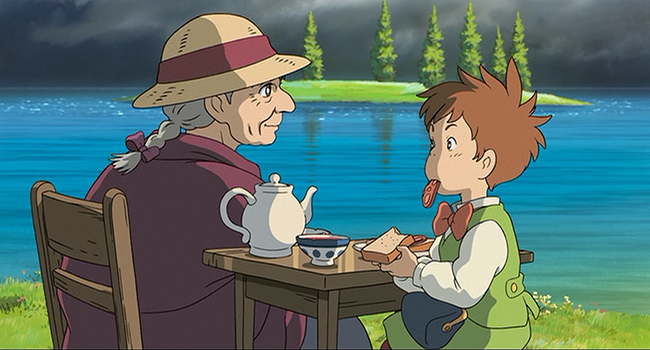

Setting aside my complaints about the movie’s overall pacing, I am grateful for the many slower, quieter moments we get. We get nice episodes that don’t primarily advance the plot but rather flesh out the characters, such as scenes where Sophie, Howl, and Markl eat breakfast together and later where Sophie and Markl picnic in the countryside.

The movie also significantly lingers on a journey up a long flight of stairs, which becomes almost a spiritual odyssey for those engaged in it.

Having brought up the characters, though, I must address the other big weakness in Howl’s Moving Castle. The movie is, among other things, a love story between Sophie and Howl. Yet I found their romance badly under-developed. At the very least, they seem to fall in love pretty quickly, given how briefly they have known each other. (The movie fudges this a bit by having them take a while to admit they are in love, but other characters see it earlier than that, and as a result it still seems fairly abrupt.)

Granted, I can see the seeds of future romance in their early scenes together. Howl is kind to Sophie, helping her first by rescuing her from the soldiers and later by giving her shelter in the castle. Plus, as noted, he’s very handsome. Sophie, meanwhile, has all the virtues one might expect from a Ghibli heroine: bravery, kindness, and a strong work ethic. Nevertheless, the movie doesn’t give us the kind of interaction between the two of them that might cause these seeds to blossom into a believable relationship. Further, Howl has more than a few bad qualities that one might expect to turn off Sophie. The viewer might be pardoned for thinking that another character in the movie, who is far more considerate, selfless, and reliable than Howl, would have been a better match for Sophie.

This problem with the love story is a serious flaw in the movie. It’s not a fatal flaw, though, because the movie’s emotional heart is ultimately not the mere fact that Sophie and Howl fall in love but rather how falling in love changes each of them.

As I mentioned, Howl has his bad qualities. When the story begins, he is stuck in a kind of perpetual adolescence, being obsessed with his looks, dalliances with women (whom he usually judges based just on their looks), and avoiding any kind of responsibility. We get a demonstration of his emotional immaturity in a scene where he throws a huge, magically tinged tantrum over his hair color changing. Howl is a kind of teenage version of Peter Pan, and his perpetually moving residence is an apt metaphor for his refusal ever to settle down in a larger sense.

Moreover, Howl’s participation in the war threatens to corrupt him further. As he transforms into the bird creature to fight, he finds it progressively harder to return to his original form. Again, we have a very clear metaphor for the character’s internal state: war quite literally de-humanizes him.

Sophie also has a significant flaw, although a more forgivable one. Years of being regarded as unattractive, and seeing herself that way, has left her without self-confidence and unable to accept herself.

Falling in love, and the various dangerous situations the story throws them into, force both Howl and Sophie to change. Motivated by his love for Sophie, Howl begins to take risks, to confront a situation he previously avoided, and to act selflessly. Meanwhile, Sophie becomes bolder and more daring, acting both to protect Howl and to stand up to him when necessary.

The personal growth both characters go through is the core of the movie. Their respective arcs culminate in a touching climax where Howl pays Sophie a compliment that reflects how he has changed and her reply does the same for her.

I also appreciated how the movie’s ending had a certain emotional nuance. While Howl and Sophie fall in love and change for the better, two other characters don’t get what they want in the end. These characters’ stories give the conclusion a more bittersweet feel and show an awareness that life doesn’t always have perfect, storybook endings.

The English dub is generally good and features not just one but two Hollywood legends. The late Jean Simmons provides elderly Sophie’s voice and effectively conveys her strength and passion; as the young Sophie, Emily Mortimer does an equally good job. The Witch of the Waste is voiced by the other screen legend, the late Lauren Bacall. Bacall is haughty and imperious in the Witch’s early scenes and then adjusts her vocal performance accordingly to show the Witch’s later vulnerability. As Howl, Christian Bale deploys his customary low, throaty delivery, which suits the cocky heartthrob (also, in a few moments when Howl is in bestial form, Bale gives us the full Batman Growl). The one weak link in the voice cast is Billy Crystal as Calcifer. Crystal might seem an appropriate choice for the snarky, peevish fire demon, but I found his delivery a little too insistently “Billy Crystal,” and it took me out of the movie as a result.

My choice for favorite image in the movie has to be the opening shot of the moving castle emerging from the fog. However, I will give an honorable mention to a lovely, oddly wistful early shot of Sophie riding a train through the city.

My favorite humanizing moment is a poignant one where young Sophie regards herself in the mirror and then, in disappointment and frustration, pulls her hat down over her face.

Also, while hardly a “human” moment, I appreciated the detail that when Howl cooks eggs, he tosses the shells to Calcifer, who gobbles up the trash. I could use that kind of fire in my own home.

In the end, Howl’s Moving Castle didn’t wholly work for me. I think its convoluted plot and under-cooked love story prevented it from entirely succeeding as a movie. Nevertheless, its dazzling visuals and powerful character development are strong points in its favor. I would pronounce it a good, but not great, entry in the Ghibli canon.

Leave a comment