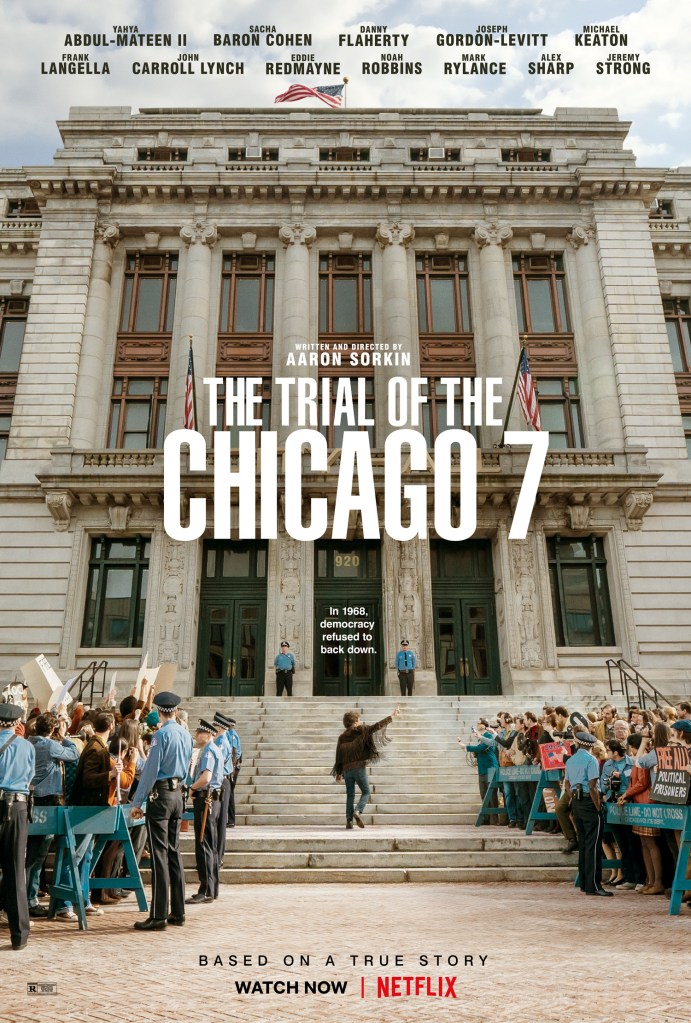

I generally do a poor job of keeping up with Oscar nominees, but I did recently catch (because the subject matter interests me) one of this year’s Best Picture nominees, The Trial of the Chicago 7. Here, a few days before the Academy Awards, I add my own small contribution to the related commentary.

Dwight Macdonald once wrote that “To write a successful novel of ideas, an author must have…ideas, or at least the ability to deal with them.” That principle applies to movies, as well, and I think provides the key to why The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020), written and directed by Aaron Sorkin, isn’t a successful movie.

The movie, a dramatization of how several notable left-wing activists were put on trial for allegedly trying to incite riots at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, has many strengths. It’s fast paced and boasts good performances and the snappy dialogue that is Sorkin’s trademark. I was rarely, if ever, bored while watching the movie and found some parts quite gripping.

What is lacking, however, is any clear theme or central idea for this movie to be about. Sorkin’s screenplay raises very interesting questions about political activism and political change that could make for a fascinating movie if explored in depth. That’s all the screenplay does with these questions, though: it raises them and has the characters spar a bit over them but doesn’t really develop them—all while spending a great deal of time on far less interesting material. In short, the author doesn’t seem to have an idea here (which is doubly frustrating because I know Sorkin has the ability to deal with them).

The titular trial unfolded from 1969 to 1970. The defendants and the organizations they represented were Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin of the Youth International Party (Yippies), Rennie Davis and Tom Hayden of Students for a Democratic Society, David Dellinger of the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, Bobby Seale of the Black Panther Party, and Lee Weiner and John Froines.

All the defendants had been present at one point or another at protests in Chicago during the Convention in August 1968. The protests were intended to express opposition to the Vietnam War even as the Democratic Party nominated pro-war presidential candidate Hubert Humphrey. They devolved into a series of confrontations between protesters and various government security forces such as the Chicago police, who repeatedly and viciously beat the protesters.

The following year, the eight activists mentioned above were indicted for conspiracy and the intent to cause a riot. Their trial was a notorious media circus, partly because of the irreverent behavior of the defendants, especially Hoffman and Rubin, and the no-less-bizarre behavior of the judge, Julius Hoffman, who showed blatant hostility to the defendants. He was especially cruel to Seale, whom he ordered bound and gagged for a portion of the trial. Seale would ultimately be separated from the trial, reducing the defendants to seven.

The Trial of the Chicago 7 covers all these events, freely jumping back and forth between the trial and flashbacks to the events in August 1968. Often a scene will cross-cut between characters recounting what happened during the protests and scenes recreating what is being described. (The movie also of course sometimes changes real-life events for dramatic purposes, but since this is a review rather than an historical evaluation, I am largely not going to delve into that. Although I will note that, contrary to what the movie would have you believe, 28th Street is nowhere near Hyde Park.)

For me, the promise and disappointment of The Trial of the Chicago 7 is captured within the first 15 minutes or so. The movie opens with a rapid-fire montage that establishes the historical context—the escalating Vietnam War, the draft’s presence in young American men’s lives, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy—and sets up our central characters. As the future defendants prepare to travel to Chicago for the Convention protests, we get thumbnail sketches of their personalities and philosophies. Hayden and Davis are shown as politically radical but serious and relatively buttoned-down personally; Hoffman and Rubin are merry pranksters who combine political activism with the hippie lifestyle; the older Dellinger is an ultra-square family man and Gandhi-style pacifist; Seale declares that Gandhi/King-style pacifism has failed and it’s time to try a different approach.

This opening precis got me quite involved, even excited. Sorkin was presenting us with characters who represented several very different perspectives on pursuing peace and social justice. As I watched, I could see the various questions that these activists’ approaches raised: Should you work within the political system or defy it? Should you adhere strictly to nonviolence or is violence sometimes justified? Should you try to earn the larger society’s respect to advance your cause or should you openly defy social convention? What is the relationship between political activism and personal lifestyle? I was anxious to see how these characters would debate these questions. Seeing Aaron Sorkin apply all his considerable skill to such debates, and how differing views on these questions affect the characters’ actions and relationships, would truly be a cinematic delight.

Then we get the movie’s second scene, and my hopes were quickly dashed. We have now flashed forward to Washington, DC, in 1969, where federal prosecutors Thomas Foran and Richard Schultz have been summoned by the new attorney general, John Mitchell. Mitchell, who doesn’t actually announce “Hi, I’m the Bad Guy,” but might as well, tells Foran and Schultz he wants them to prosecute the activists. Schultz, being a decent fellow, protests and explains why prosecution would be unwise and unjust. Mitchell insists, though, and so the terrible, politically motivated miscarriage of justice goes forward.

The scene is disappointing partly for its on-the-nose dialogue and complete lack of subtlety but also because it shifts the movie’s focus from the battle of ideas among the activist protagonists to how those protagonists were railroaded by the Corrupt Establishment. This conflict is far less interesting, at least to me, because, unlike the struggles among the activists, one side is so obviously wrong that no real complexity is possible.

I am not questioning the essential accuracy of how the movie portrays the judicial system and its treatment of the defendants, just the portrayal’s inferior dramatic potential. Seeing flawed but intelligent people clash over complex issues can be fascinating; seeing such people struggle against and score points off cartoonishly evil villains is a much more limited type of entertainment.

However, even a simplistic tale of progressive Davids battling a reactionary Goliath would at least make for a coherent movie. Yet Sorkin hasn’t made that movie, either. Instead, The Trial of the Chicago 7 is multiple, disparate stories slapped together. We get some scenes about the trial’s unfairness, some scenes about the 1968 unrest, some scenes about the clashes among the defendants and their differing views, but none of it is really developed into a satisfying dramatic whole.

The trial scenes, for example, variously show us Judge Hoffman’s biased behavior, juror tampering, the presence of government informers among the protestors, and the First Amendment implications of prosecuting people for merely intended actions. Because none of these elements are developed in any detail, though, they don’t offer any particular insight into civil liberties or government repression of dissent beyond emphasizing the obvious point that “this is all really unfair.”

We also see arguments among the defendants over strategy, with Hoffman and Hayden being the main sparring partners. These scenes offer intriguing glimpses of the movie that could have been, as Hoffman argues for “cultural revolution” and using the trial as a platform for his views and Hayden argues for winning elections and just getting through the trial as quickly as possible so they can get back to their day-to-day activism. Again, though, the arguments are given minimal screen time and don’t have the weight they could have. I was never entirely clear what Hoffman’s views were or how he envisioned anti-war politics and a cultural agenda of drug use and free love as reinforcing each other. That’s a definite limitation if you are trying to dramatize a contest of ideas.

Meanwhile, other characters and their views get short shrift. Dellinger’s advocacy of principled nonviolence would have added a valuable alternative perspective, but the screenplay never gives him a chance to explain those beliefs. Seale, despite a memorable introduction and an intense performance by Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, is relegated for much of the movie to arguing with Judge Hoffman and insisting he had nothing to do with the other defendants. What precisely he believed about Black empowerment and political change remains murky. Indeed, Seale’s character best exemplifies the split at the heart of the screenplay: as a leader of the Black Panther Party and figure in radical 1960s-era politics, Seale was a significant figure; as a figure in the Chicago trial, he was an awkwardly squeezed-in defendant who didn’t even remain part of the trial to the end.

Perhaps because of the screenplay’s uncertain focus, Sorkin struggles to give the story momentum or shape it toward a climax. The unexpected testimony of a star witness, who is introduced into the movie with great fanfare, is presented as a crucial turning point in the trial. Yet the witness’ testimony has no impact on the trial’s outcome nor does it tell the audience much about the case apart from the political motivation behind the prosecution—which we already knew about from the early scene with John Mitchell.

Toward the end of its runtime, The Trial of the Chicago 7 zeroes in on Tom Hayden, who is the only character to get anything approaching an arc. Hayden’s role in the 1968 unrest is explored in a scene that is clearly meant to have great dramatic weight, and the movie’s conclusion revolves around a consequential decision by Hayden. However, I must admit that I don’t understand what these scenes are supposed to tell us about Hayden or how his character changes.

Earlier in the movie, Hayden is portrayed as cautious, even timid, in his willingness to challenge the political establishment. Then the revelation about his role in the unrest seems to suggest that no, he’s actually an impulsive hothead. Then the movie almost immediately takes back this claim, saying (rather unconvincingly), wait, he’s not a hothead, he simply expressed himself in ways that were misunderstood as incendiary. This isn’t character development; it’s confusion. This authorial dithering isn’t helped by including a sudden, unconvincing reconciliation between Hayden and Hoffman.

Hayden’s final decision doesn’t make matters any clearer. The decision seems to demonstrate Hayden’s willingness to reject respectability and embrace a more defiant, revolutionary stance. Yet the closing title card then tells us of his later, more conventional career in electoral politics. So, which is it? What should we take away from this?

I should add that this final scene is so laughable in its over-the-top attempt to provide an inspiring, crowd-pleasing ending to the movie that I can easily imagine the ghost of Frank Capra saying “I don’t know, this seems a little hokey to me.”

What makes all these story-level flaws even more frustrating is the tremendous skill with which the rest of the movie is made. Plenty of individual scenes are effective, even powerful. Sorkin’s brand of hyper-articulate repartee is consistently a pleasure to listen to and some exchanges are quite funny. I will cite just two of my favorite examples:

When a staffer for the defendants’ legal defense team answers the telephone, she responds to the caller, “We sure do take contributions.” Then, in response to the caller’s further question:

STAFFER: We can’t take grass.

HOFFMAN (overhearing): Hey!

STAFFER: Yeah, Abbie says we’ll take the weed.

At another point, the defendants get into an argument over their strategy and courtroom behavior:

HAYDEN: Are we using this trial to defend ourselves against very serious charges that could land us in prison for 10 years? Or are we using it to say a pointless “f— you” to the Establishment?

RUBIN: F— you!

HAYDEN: That is what I was afraid…(beat) Wait, I don’t know if you were saying “f— you” as your answer, or…?

HOFFMAN: I was also confused.

The acting is generally good and sometimes excellent. A trio of British actors, Sacha Baron Cohen, Eddie Redmayne, and Mark Rylance, all give memorable performances as Hoffman, Hayden, and defense attorney William Kunstler, respectively. I especially like Rylance’s portrait of a gadfly whose radicalism is leavened by a certain world-weary bemusement.

Even more impressive, because they have less flashy roles, are a couple of supporting players. As Rennie Davis, Alex Sharp comes across initially as a rather milquetoast nerd; yet Sharp conveys an inner conviction and ferocity that makes Davis compelling. Caitlin FitzGerald, as an FBI agent who infiltrates the protestors by cozying up to Jerry Rubin, plays an underwritten part with intelligence and subtlety. The agent doesn’t have any big conversion to the protestors’ side, but she doesn’t come across as a villain or caricature either.

Also, Sorkin shows himself to be a capable director. While most of the staging and shot choices don’t draw attention to themselves, we get a couple noticeable tracking shots of the courtroom and the defendants’ headquarters that give a sense of the bustle in these large, crowded rooms. A violent confrontation between protestors and police, presented in flashback midway through the movie, is also handled well. Extras, editing, and music combine here to create a terrifying depiction of how a situation can escalate.

So much works well in The Trial of the Chicago 7, and the story had such dramatic potential, that I regret how disappointing the final result is. As skilled a screenwriter as he is, I think Aaron Sorkin might have benefited from a collaborator on this one.

Leave a comment