Continuing with my Studio Ghibli retrospective, I turn to the Big One: Spirited Away.

Among Studio Ghibli’s movies, Spirited Away (2001) is the crown jewel. Certainly it is the most commercially successful movie the studio ever produced, grossing over 30 million yen and standing for almost 20 years as the top-grossing movie in Japanese history (last year’s Demon Slayer finally knocked it down to second place). Spirited Away is the only Studio Ghibli movie—indeed, the only anime movie—ever to win an Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. The New York Times rated Spirited Away the number one Studio Ghibli movie, and it turns up in similarly high positions in most rankings of the studio’s products. At one point, Sight and Sound even included it in the list of the greatest movies of all time.

For my part, I diverge slightly from the adulation surrounding Spirited Away. The movie is definitely great and I like it. I don’t love it, though; several other Ghibli movies would be above it in my own personal ranking. In this review, I will try to do justice to the movie’s many strengths that have understandably earned it such success. I will also try to explain why I don’t have quite the same reaction to it as many others have.

Written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki, the movie begins with young Chihiro and her parents driving to their new home in a new town. Along the way, they take a wrong turn down a back road and dead end at what appears to be an abandoned amusement park. Chihiro is scared by the place, but her parents insist on exploring.

Within the park, they find an open but unattended restaurant, and the parents begin gorging themselves on trays of delectable food that have been set out. Chihiro wanders through the park’s streets and meets a mysterious boy named Haku who warns her that night is falling and she has to leave this place right away. It’s too late, though: as the sun sets, the park fills with all sorts of monstrous and fantastical creatures. Worse, Chihiro’s parents have been transformed by the (enchanted) food they were eating into pigs.

We soon learn that what seemed to be an amusement park is actually a mini-city in which inhabitants of the spirit world gather. The central institution of this city is an enormous Bath House where spirits go to relax and refresh themselves. The Bath House is ruled by Yubaba, a cruel and greedy witch.

Deprived of her parents and alone in a strange new world, Chihiro must somehow survive. Aided by Haku and some of the other, kinder residents of the spirit world, she gets a job as a menial worker in the Bath House. (In a folk-tale-like detail, the evil Yubaba is still bound by certain rules and cannot refuse someone who asks her for a job.) As she works, Chihiro hopes she can somehow save her parents and return to the human world.

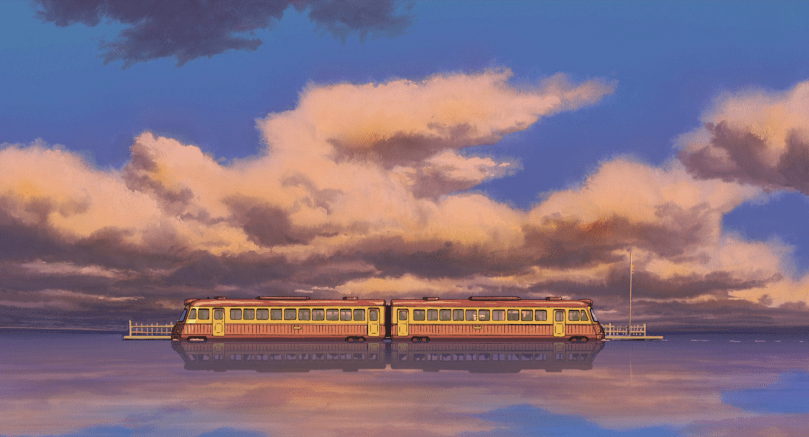

Spirited Away contains much to praise, but above all praise must go to the amazing world-building and character design from Miyazaki and his animators here. The Bath House is one of the great movie locations, a multi-storey red building standing amid a vast plain that floods when it rains. The building’s interior stretches from the grungy subterranean boiler room that heats the Bath House water; through the middle levels, filled with warm yellow light, of elegant baths; to the palatial top storeys (all marble, rugs, and painted vases) where Yubaba lives. Outside, a railroad track stretches across the plain and occasionally a lonely train runs past the Bath House. When the plain floods, the train seems to be crossing the sea.

The supernatural characters are no less vivid or memorable than the setting. The Bath House is staffed largely by what look like anthropomorphic frogs. Yet these frogmen are not all alike but instead seem to exist on a spectrum running from more frog-like to more human. One is simply a talking frog, while others look more humanoid.

We also get glimpses of various Bath House patrons, who include massive ducks and a red-and-white “radish spirit,” who resembles a cross between a walrus and a sumo wrestler.

Downstairs, the boiler room is run by Kamaji, a bald old man with a huge mustache—and six arms. The extra arms allow him to multi-task in his work, and he also walks about on them in a spider-like fashion. In supplying coal to the boiler, he is aided by none other than the soot sprites, last seen in My Neighbor Totoro.

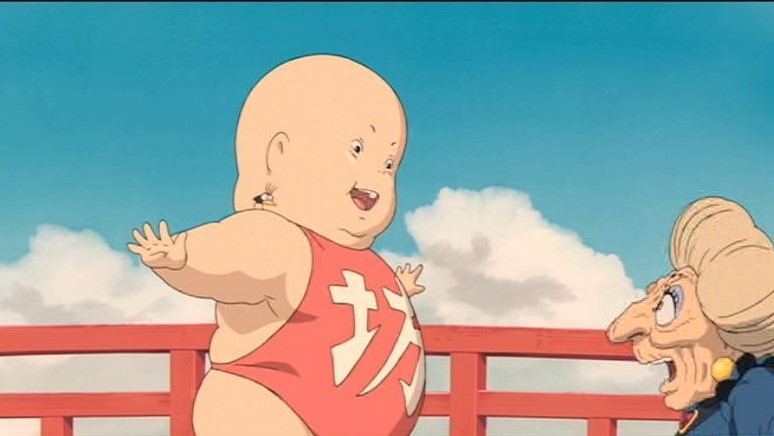

The Bath House’s overlord, Yubaba, is a giantess whose head accounts for about half her entire towering stature. She sports talon-like red nails and enough gaudy jeweled rings to put a certain Beatle to shame. When she needs to travel outside the Bath House, she can transform into a great bird. Even bigger than Yubaba is her child, who looks like an infant but is perhaps 10 feet tall and like his mother is anything but sweet natured.

Compared to this mother-son pair, Haku (who works as Yubaba’s assistant) seems a relatively normal-looking boy. Haku takes another form, though: a silvery flying dragon.

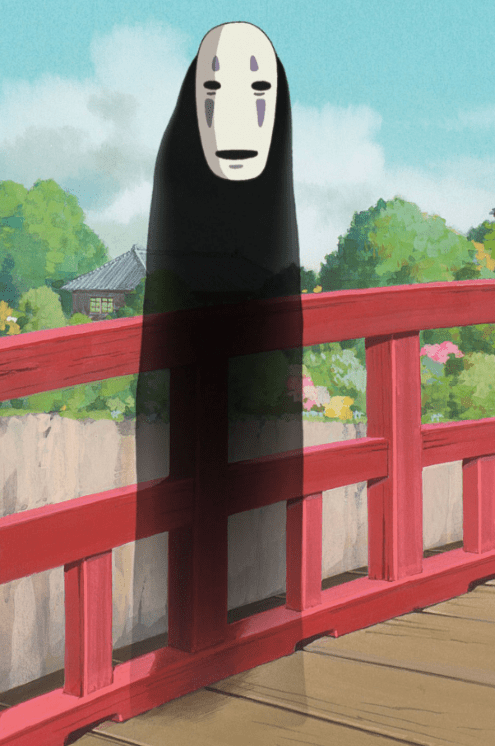

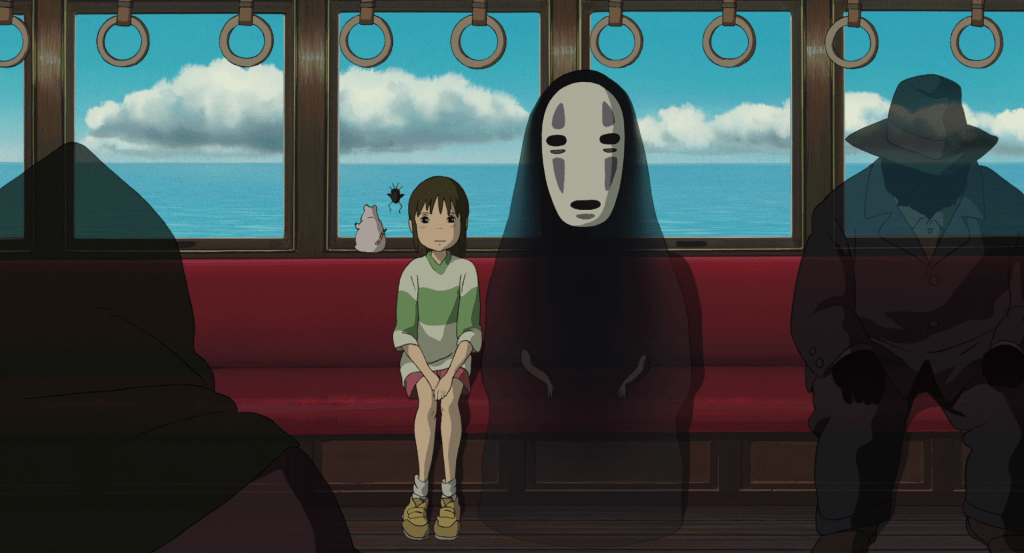

The supernatural beings in Spirited Away also include what is probably Studio Ghibli’s most iconic creature, after Totoro. This would be the aptly named “No Face,” a tall spectral figure who wears a mask with a face painted on it. In keeping with its ghostly quality, No Face cannot speak but communicates in quiet, gasping noises.

And believe me, dear reader, these descriptions of setting and characters only begin to scratch the surface of the grotesquerie and creativity on display in Spirited Away. Miyazaki and his animators seem to have made the choice, when drawing this movie, never to pass up an opportunity to add something bizarre or outlandish.

For example, Yubaba has been given three attendants (or pets?) who are just bouncing, disembodied heads. This trio don’t, for the most part, contribute anything to the plot; they are just a detail of the world. Similar bits of throwaway inventiveness abound. If Chihiro must do something as simple as open a door, she is confronted by a talking door knocker. When she and some companions must make a nighttime journey through the woods, they are aided by a pole-mounted lantern that hops along on a single big foot.

This riot of surrealistic visuals recalls variously Disney’s adaptation of Alice in Wonderland , the trippy world of Yellow Submarine, and Jim Henson’s Labyrinth. The filmmakers have used animation’s possibilities to the fullest here.

The flamboyance of the supernatural world risks overshadowing another great strength of Spirited Away: its protagonist. Chihiro is one of Miyazaki’s best heroines.

In keeping with the movie’s general visual creativity, Chihiro’s distinctiveness begins with her character design. She is an ordinary human girl, not a supernatural being, yet she stands out in her own way as much as any of the other characters.

For all Ghibli animators’ skill in drawing landscapes, animals, and magical beings, the drawing of young human protagonists tends to be fairly generic. We often get a basic “anime child” who, like a character in an editorial cartoon, is identifiable by one or two basic features. Sheeta has pigtails, Satsuki has short hair, Kiki wears a red bow—but swap around their hairstyles and costumes, and it would take an eagle-eyed viewer to tell them apart.

But not Chihiro. Chihiro doesn’t look like any other Ghibli heroine. Her pudgy cheeks, narrower eyes, and stick-like arms and legs make her instantly recognizable. You couldn’t mistake her for anyone other than herself.

She also has her own recognizable body language, being a klutz who frequently stumbles or takes pratfalls. Her clumsiness is demonstrated in a scary and funny scene in which she must descend a long, rickety flight of wooden stairs. Chihiro begins very slowly and cautiously, almost climbing down the stairs. Then a breaking step makes her lose her footing, and she rapidly half falls, half runs down the remaining steps before face planting into a wall at the bottom of the stairs.

Her distinctiveness goes beyond just how she looks and moves. As I have noted in other Ghibli reviews, character development is not Miyazaki’s strong point. As appealing or striking as they are, characters such as Satsuki and Mei or Ashitaka and San don’t change much over the course of their movies. (Porco Rosso hints at a change in Marco but leaves this point ambiguous.)

By contrast, Chihiro has a full character arc. She begins the movie as a petulant, timid child, full of self-pity over having to leave her old home and friends behind. Forced to fend for herself in this strange and dangerous new environment, she must become braver and more self-confident. As crises threaten the Bath House and its inhabitants, Chihiro rises to the occasion and resolves the crises. She earns the other characters’ respect and, by the movie’s end, is strong enough to stand up to Yubaba.

Inter-twined with Chihiro’s growing courage is another crucial characteristic: she is kind to others. Her kindness is shown early on in a small moment when she relieves a sootsprite in the boiler room from carrying an especially heavy piece of coal. (This triggers a funny little rebellion of other sootsprites against their burdens.) Later, she lets No Face, who is standing outside in the rain, into the Bath House. At first, given No Face’s ominous appearance, this choice seems like dangerous naivete on Chihiro’s part. Yet the choice establishes a relationship with this phantom-like being that serves Chihiro and others well later in the movie. She aids a repugnant Bath House customer who turns out to be in desperate need of help—and proves her worth to her fellow employees in the process. Meanwhile, her innate kindness and sense of gratitude to Haku, who helped her earlier, spurs Chihiro to take great risks to help him.

Her kindness sets her apart from most of the spirit world’s inhabitants. Yubaba, her monstrous child, and many of the Bath House employees are selfish, greedy, petty people. Chihiro’s very different ways have a good influence on those around her.

Her consideration for Yubaba’s child, when the child is placed in a vulnerable situation, helps him become less spoiled and more independent than he had been in the witch’s care. Chihiro helps No Face change from a potentially monstrous being into a content one with a home of its own. The creature’s threat, one gathers, stems from a kind of voracious neediness and Chihiro helps No Face satisfy that need. She similarly saves Haku’s life and sets him free from an enchanted imprisonment. While another type of story might show how a supernatural being transforms the everyday world, Spirited Away shows how a kind girl from the everyday world transforms a supernatural one.

Great scenes abound in Spirited Away, but I will highlight a few stand-out sequences. The opening, in which Chihiro and her parents are drawn into the spirit world, is a masterful little set piece of mounting dread. The backroad they drive down is lined by shrines, signaling a journey to somewhere outside normal human life. As they drive, Chihiro notices a gnome-like statue, covered in moss, with a sinister grin on its face. A long dark tunnel marks the entrance to the “amusement park.” As the family stands outside the entrance a soft breeze blows leaves toward the tunnel; a frightened Chihiro says that the wind is “pulling us in.”

When they go down the tunnel, they pass through what looks like a long-abandoned waiting room, lined with benches. After they emerge again into the sunlight and begin to explore the spirit city, everything seems more or less normal. The absence of people, Chihiro’s agitation, and our awareness that the family is getting further and further away from civilization with every step keeps up the tension, though.

Once Chihiro gets the warning from Haku and dusk falls, the menace really kicks into high gear. The sky darkens, the spirit city’s buildings light up, and half-human, wraith-like figures start rising up out of the ground. An understandably panicked Chihiro runs through the city streets to find her parents only to be met with the sight of them now changed into beasts. The sequence is brilliantly disturbing and recalls both The Odyssey and horror movies (I was reminded of the “Humgoo” segment of The Monster’s Club, which terrified me when I caught it on TV as a kid).

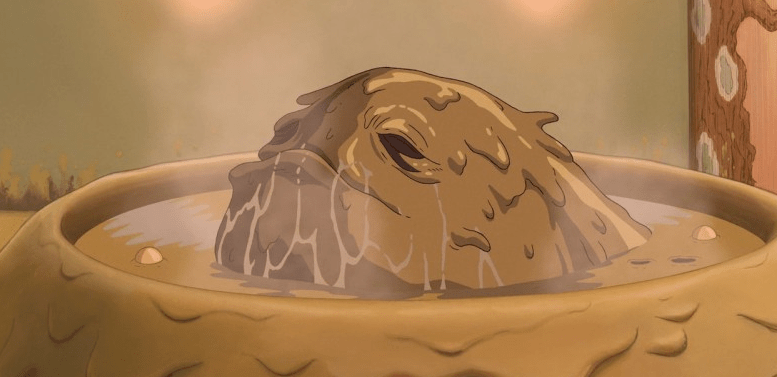

Another great sequence is at the movie’s midpoint, when Chihiro must deal with the repugnant Bath House customer: a foul-smelling creature referred to as a “Stink Spirit” that resembles a huge, sentient mound of sewage.

Everyone recoils from the Stink Spirit but Chihiro is forced to attend to it—a nice touch is how her hair stands on end in reaction to the spirit’s odor and touch. She runs a bath for the spirit and finds that there is more to this customer than meets the eye. Soon all her fellow workers and even Yubaba are joining with her in a group effort to relieve the spirit’s obvious distress. The distress’ cause, once discovered, is both funny and subtly significant (and carries echoes of Jaws!). The bath workers’ efforts build to a crescendo; then comes a quiet, eerie encounter; and then the catharsis of the spirit’s sudden freedom from its burden.

The episode deftly blends so many elements: both gross-out horror and humor; suspense over whether Chihiro can rise to a daunting challenge; the amusement of the familiar appearing in an unfamiliar setting; and the spooky beauty of an unearthly being.

The last sequence that sticks in my mind is when Chihiro, No Face, and their companions travel on the train that runs by the Bath House. The only other passengers are ghostly shadows. We never learn who or what these shadow passengers are, but their presence, combined with the train’s course through calm, sunlit waters, give the ride the feel of a journey into the afterlife. It’s a haunting, melancholy passage.

Without a doubt, Spirited Away is extraordinary. Why then do I not rate the movie quite as highly as many others do? Why do I not like it as much as, say, Princess Mononoke?

I would identify two reasons. First, of all the adjectives I could use to describe Spirited Away—I have already used “monstrous,” “fantastical,” “amazing,” “vivid,” “grotesque,” and “bizarre” or their variants—one that I would not use is “magical.” The spirit world and its denizens, for all the flair with which they are rendered, are not very otherworldly.

When I watch Totoro or the Spirit of the Forest, I sense the presence of something profoundly alien and non-human, beings with ways radically different from our own. When I watch Yubaba and most of the other Bath House inhabitants, I sense beings who, appearances aside, are pretty much like humans. They have typical human motivations: greed, vanity, fear, and occasional nobler impulses such as kindness and loyalty. The Bath House is in many ways just another terrible workplace, filled with grueling labor, friendly or back-biting co-workers, and a tyrannical boss.

To me, such characters and settings are less interesting than the genuinely magical, non-human creations that I know Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli are capable of. The three sequences I mentioned above are notable partly because they come closer to evoking that sense of mystery. During most of Spirited Away, however, I find myself marveling at the animators’ skill in drawing the spirit world and its residents rather than responding to either on an imaginative or emotional level.

My second problem with Spirited Away is that the movie runs out of steam at the end. Late in the movie, we see two crucial encounters between Chihiro and another character: in one case, Haku, in the other, Yubaba. These encounters are presumably meant to provide some resolution to Chihiro’s journey into the spirit world. Neither quite work, though.

The scene with Haku involves a revelation about him and his relationship to Chihiro. The revelation has been prepared for: we get hints and foreshadowing earlier in the movie. The scene is also beautifully staged, in a way James Barrie would have appreciated.

Yet the preparation and execution cannot wholly hide the fact that we are just hearing exposition. The information we are getting relates to events that happened long before the movie began and that we largely don’t see. Also, I am not sure the revelation really adds that much to Chihiro and Haku’s already well-established relationship. Yes, I admit I am moved by the scene. But I am responding to the staging, the animation, and Joe Hisaishi’s great score, not the inherent dramatic power of the moment. The scene is ultimately a case of telling, rather than showing.

The scene with Yubaba features the final confrontation between her and Chihiro. As show-downs go, this one is pretty anti-climactic. Granted, I think this is intentional. Miyazaki doesn’t spend time building an elaborate, suspenseful clash between heroine and villain because that would distract from the main point: how Chihiro has grown during the movie. Nevertheless, even an intentional anti-climax is still an anti-climax. The scene falls rather flat for me.

For all its many strengths, Spirited Away doesn’t find an ending that packs an emotional punch worthy of what has come before. (Although the quiet final scene does have power; I particularly liked two key moments where Chihiro silently reflects.) Together with the relatively prosaic qualities of the spirit world, this keeps me from placing the movie in the absolute top tier of Ghibli movies.

The English dub voice cast is good, and two voice actors are excellent. As Chihiro, Daveigh Chase (who was also the voice of Lilo in Lilo and Stitch) sounds very young and rather whiny, which fits our heroine. Beyond having the right vocal quality, though, Chase conveys the girl’s emotions and development—she gives us the character behind the callow voice. As Yubaba, Suzanne Pleshette cackles, screeches, gloats, and rages with all the gusto we would expect from the Bath House’s despot.

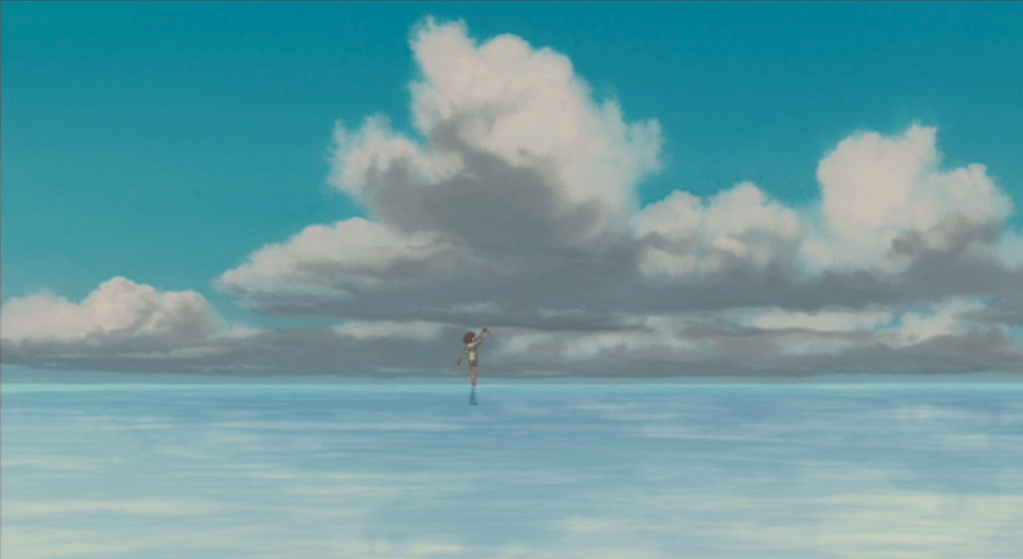

My choice for favorite image in Spirited Away is a toss-up between two shots that both place Chihiro against the backdrop of the flooded plain around the Bath House. One nighttime shot shows Chihiro sitting on a Bath House balcony watching a train move across the plain. It’s a lonely, poignant image.

The other shot is an ethereal one of Chihiro walking across the plain. The water around her makes her appear to be moving through the sky.

My favorite humanizing detail is when early on Chihiro must walk up some stone steps in the spirit city. Being too small to move her feet alternately from one step to another, she puts one foot on the next step, then moves the other foot to the same step, then repeats. The detail is characteristically subtle but accurate: that is how kids handle large steps.

Notwithstanding my reservations, Spirited Away is definitely a great movie. If Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli had made only this work, they would have secured their reputations as first-rate animators. Yet this movie came as the culmination of a 15-year winning streak of movies that range from “good” to “excellent.” That truly is magical.

Leave a comment