Next in my Studio Ghibli retrospective, I look at My Neighbors the Yamadas.

Imagine the kind of single-panel cartoon made famous by the New Yorker. Such cartoons are typically ironic, perhaps somewhat satirical, and, above all, elliptical. The limitations imposed by one drawing with a caption often require you, the reader, to fill in the context or details implied by what is on the page. A New Yorker cartoon can also be maddeningly opaque: you might not be sure if the joke is so subtle that you are missing it or if the cartoon simply isn’t that funny.

Now, can you imagine a whole movie that is essentially one big New Yorker cartoon? Well, if not, you can always just watch Studio Ghibli’s My Neighbors the Yamadas (1999), which provides much the same experience.

Written and directed by Isao Takahata, My Neighbors the Yamadas is based on a long-running newspaper comic strip drawn by Hisaichi Ishii. Like its source material, the movie is an essentially comedic take on the life of the titular Japanese family. It has no story to speak of; as with a collection of newspaper or magazine cartoons, the movie is just a series of short vignettes about the Yamadas and their interactions with each other and occasionally with the outside world. Also, unlike prior Studio Ghibli projects, this movie was entirely computer generated. The resulting animation follows closely what I gather is the look of the original comic strip.

The members of the Yamada family are all stock characters familiar from innumerable sitcoms and similar comedies about domestic life. We have Takashi, the blustering yet beleaguered working-stiff dad; Matsuko, the fretful and rather silly homemaker mom; Noboru, the awkward, somewhat smart-alecky adolescent son; Nonoko, the cute and precocious young daughter; and Shige, the crotchety, sharp-tongued grandmother. Unlike sitcoms, though, the movie doesn’t contain absurd, over-the-top scenarios or conflicts. The brevity of each little episode doesn’t allow for such elaborate plotting, and in any case Takahata is aiming for something more low-key in tone.

Instead, we get a series of skits depicting relatively realistic situations that nevertheless involve some kind of comical reversal or deflation of expectations. In one vignette, Matsuko uses reverse psychology to con Shige into cooking dinner but gets a different result than she hoped for. In another, Takashi tries to play ball with Noboru, but the attempted father-son bonding descends into bickering and a broken window. Noboru takes a bath to refresh himself in advance of a night of studying, only for the bath to send him right to sleep. Shige tries to teach some neighborhood kids the value of honesty but things don’t go according to plan.

These skits are grouped into short sections with their own loose themes. Like chapters in a book, the sections are introduced with title cards that offer some ironic counterpoint to the events on screen. Scenes of Takashi and Matsuko bickering bear the title “Marriage, Yamada-style”; various examples of Matsuko’s daffy behavior around the house are entitled “Domestic Goddess.” Also, a voice-over narration periodically breaks in to recite a haiku that somehow comments on the events on screen.

The movie’s visual style is what I can describe only as “aggressive minimalism.” The main characters are very simply drawn, being not much more than collections of a few lines, colors, and basic shapes. To mention just one example of this extreme stylization, the various Yamadas’ hands are often rendered as mere blobs, without discernible fingers. Further, many background characters are barely drawn at all: figures in a crowd or on a train or on TV are often mere silhouettes. Rooms, streets, and other backdrops are also greatly simplified, if they are even there at all: in many shots, huge parts of the frame are occupied by blank space. The effect is rather like Takahata decided to take the child’s-drawing-style of the flashback sequences in Only Yesterday and to push that style to a new extreme.

Perhaps liberated by this unabashedly stylized approach, Takahata and his animators frequently depart from any semblance of realism to embrace a more figurative approach. When Shige argues with an elderly man whom one gathers she has known since youth, she transforms before our eyes back into the young girl she used to be. When Noboru thinks of Matsuko’s frequent nagging, we see an endlessly duplicated array of mothers materialize around him, all repeating, in one great cacophony, “Study harder.”

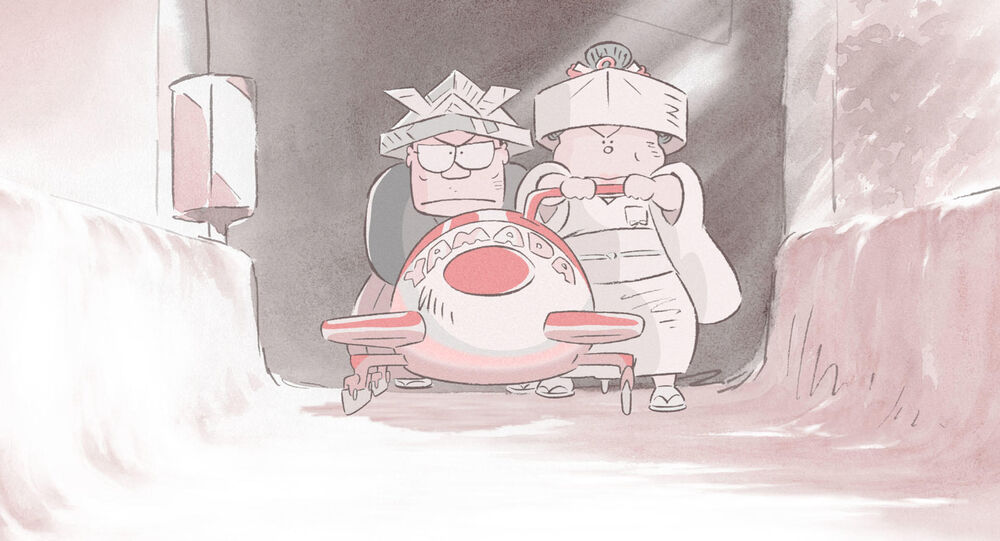

Two sequences stand out for visual inventiveness. The first is a flashback to Takashi and Matusko’s wedding, at which an elderly relative offers advice about the trials of marriage and the importance of children. As the relative speaks, the movie becomes a dizzying montage of metaphorical images of married and family life. We see Takashi and Matsuko jump into a bobsled (labeled “Yamada”) and race it down the snowy slope of what is revealed to be a gigantic wedding cake; the bobsled morphs into a sailboat on rocky seas; then a tractor riding through a field in which newborn babies are sprouting out of the ground; and so on.

The sequence also works in some nice visual references. The journey of the Yamadas’ sailboat re-creates Hokusai’s famous Great Wave print, while the arrival of Noboru and Nonoko are metaphorically represented by allusions to the folktales of Momotaro the Peach Boy and The Bamboo-Cutter and the Moon-Child (the latter being a story Takahata would revisit).

The second inventive sequence comes when a gang of rowdy, noisy, and possibly dangerous bikers disturbs the Yamadas’ neighborhood. Shige, Matsuko, and Takashi must improvise some kind of response to the troublemakers. When Takashi leaves the family home to talk to the bikers, the whole visual style of the movie abruptly changes. The simple, cartoon-strip aesthetic is replaced with a far more detailed and naturalistic look, rendered in a way reminiscent of a pencil sketch. The characters now look and move like real people, while the background looks like a real city street.

The visual change starkly signals the shift from the funny, warm domestic world of the rest of the movie to the dangerous situation that now threatens it. When the danger diminishes, the old visual style returns. In addition to the clever use of animation, the sequence is written in a way that avoids obvious drama and hits a variety of emotional notes: scary, then funny, and finally rather sad.

The movie’s English dub works well. Led by Saturday Night Live alums Jim Belushi (as Takashi) and Molly Shannon (as Matsuko), the actors give energetic vocal performances that suit the broadly drawn (in multiple senses) characters and give vitality to what would otherwise be a meandering movie. Meanwhile, as the narrator, David Ogden Stiers delivers the chapter titles and haikus with appropriately cool authority.

Rather like your reaction to New Yorker cartoons, whether you enjoy My Neighbors the Yamadas’ collection of understated comic vignettes will very much depend on your own sensibility and even your mood at the time of viewing. Some people will find it funny and charming, while others will find it merely lame and inconsequential.

For my part, I enjoyed it. I laughed out loud several times. I will mention just a few of the moments I found most amusing. In one scene, Matusko and Shige observe a cherry blossom tree as they walk down on the street.

SHIGE: How beautiful! (pause, then wistfully) I wonder how many more times I’ll see the cherry blossoms in bloom.

MATSUKO: What are you talking about, Mother? You’re still young. You’re only 70!

(beat)

SHIGE: About 30 more times, then, I guess.

(Matusko freezes, aghast, then faints)

Another scene shows Takashi, commuting home from the office one evening, arrive at the local train station only to find it raining—and he doesn’t have an umbrella. He calls home to see if someone can meet him with an umbrella. We then get the following exchange over the phone:

TAKASHI: Yeah, can you bring my umbrella to the station?

MATSUKO: Noboru, your father is at the station. He needs an umbrella.

NOBORU: Can’t someone else do it? I’m studying!

SHIGE: Why don’t you go? When’s the last time you two shared an umbrella?

MATSUKO: Oh, I just don’t feel like it right now.

SHIGE: Excuse me!

MATSUKO: Noboru, can’t you just take it to him?

NOBORU: Send Nonoko!

TAKASHI (exasperated): Oh, forget it! I’ll just go buy one!

MATUSKO: Great! Pick up some ground beef too.

That this squabbling is soon followed by an unexpectedly sweet resolution provides a nice balance to the episode.

The movie also has some good visual comedy in a scene where Takashi and Matsuko have an elaborate duel of sorts over control of the family TV. Also, not all the best vignettes are funny. An episode where Shige visits a friend who is in the hospital is arrestingly poignant. A quiet scene where a grouchy, exhausted Takashi returns home from work and numbly eats some food while Matsuko watches TV next to him manages to be both melancholy and oddly comforting.

Other episodes don’t work as well. In general, the shorter vignettes are better. I didn’t care much for an extended sequence where Nonoko gets lost at the mall and the rest of the family freaks out as a result. Another longish bit about various Yamadas being absent-minded and leaving home without bringing along various personal items fell similarly flat. Still, good or bad, none of the vignettes last all that long: as in an anthology of cartoons, if one entry isn’t to your liking, you can just go on to the next one!

My favorite image from My Neighbors the Yamadas is from that episode where Takashi must return home from the train station in the rain. In portraying the city streets at dusk, the animators capture how the rainfall diffuses the light of the street lamps and storefronts to create a rainbow-like shimmer. This effect, when combined with the minimalist drawing, gives the movie a lovely watercolor look.

My favorite humanizing detail is from an episode where Matsuko stops Noboru, who has just returned home, to ask what is it that her son bought at the bookstore and has now brought home in a brown paper bag? Noboru freezes in place and, as Matsuko approaches, mutely hands his mother the purchase. We don’t see Noboru’s face at the moment of hand-off but just watch him from behind as he stands rooted in place, his stiff posture broadcasting embarrassment and dread. It’s a funny, pitiable bit of body language. (That his bookstore purchase turns out to be far more innocuous than we might expect is in keeping with both the movie’s penchant for defying expectations and overall wholesome tone.)

My Neighbors the Yamadas is not a great Ghibli movie, by any stretch. It’s as insubstantial as a soap bubble and doesn’t have anything more complex or unusual to say than “Members of a family can love each other—even while they drive each other crazy!” (Indeed, that is pretty much the message of a laughably inept wedding toast Takashi gives at the conclusion.) Still, the movie is cute and sweet and finds a tone that is both relaxed and relaxing. And, if nothing else, it again demonstrates Takahata’s effort to try something dramatically different in each movie he made.

Leave a comment