I continue my Studio Ghibli retrospective with a look at the outstanding Princess Mononoke.

“This book is like lightning from a clear sky…[I]n it heroic romance, gorgeous, eloquent, and unashamed, has suddenly returned…here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron; here is a book that will break your heart.”

The passage above was written by C. S. Lewis in his 1954 review of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. If you substitute “movie” for “book,” however, every word would apply with equal force to the soaring triumph that is Princess Mononoke (1997), written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki.

Princess Mononoke contains many of the same elements as previous Ghibli movies: a preoccupation with Japan’s history; a concern for the relationship between humans and nature; and strong female characters. Yet Miyazaki has assembled these elements into a wholly different kind of movie from any previous Ghibli entry. Princess Mononoke is a full-blown fantasy epic, complete with gods and spirits; magic and curses; duels, battles, and quests; and the beauties of the natural world, all rendered with Studio Ghibli’s immense skills.

This movie also finds an overall atmosphere and tone that differs from previous Ghibli movies. We get a gravity that contrasts with the light-hearted adventure of Castle in the Sky or Porco Rosso, the childlike wonder of My Neighbor Totoro, or even the dark comedy of Pom Poko. Here we are watching a tragedy. Yet the tragedy is not primarily a personal one, as in Grave of the Fireflies’ raw, painful wartime story. Princess Mononoke is about a tragedy for the natural world and for all humanity.

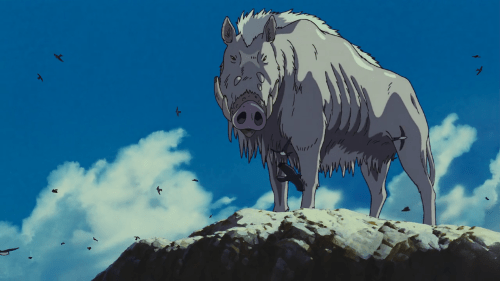

Set in Japan’s distant past, the story begins in the isolated community of an indigenous people, the Emishi. The community is threatened by a monster that emerges from the nearby forest, and an Emishi prince, Ashitaka, must defend his home against the creature. He kills it, but not before being maimed in the process.

The opening attack on the Emishi village is one of several great action sequences in Princess Mononoke. Miyazaki builds suspense as Ashitaka and the village watchman see signs of something moving amid the trees at the village’s outskirts. When the monster finally emerges, we get the first of the movie’s many extraordinary character designs. Resembling an enormous spider composed of innumerable wriggling black tentacles, the beast is terrifying to behold. Adding to its fearsomeness is how its touch blights the trees and grass around it.

Ashitaka, riding on a red elk named Yakul, tries to fell the monster with his bow and arrow. Here, the animators understand that speed and clarity about where all the characters are in relation to each other is crucial to making a chase or other action sequence exciting. The viewer sweeps along with Ashitaka and Yakul as they ride around the monster, trying to stay between it and the villagers.

The slain beast turns out to be a boar god that had become sick and accursed after being shot with an iron musket ball. (In the movie’s cosmology, gods are extraordinarily powerful but not immortal and invulnerable.) His wounding by the god-turned-monster means that Ashitaka is now also accursed and will inevitably fall prey to the same sickness. He leaves his community behind and begins wandering the country, trying to find the origin of the musket ball that caused so much harm.

Ashitaka’s quest leads him to the walled city of Irontown. Under the rule of Lady Eboshi, Irontown’s inhabitants make weaponry—guns and bullets—and are in the process of cutting down the surrounding forest as part of their industrial expansion. This has created conflict between the people of Irontown and the gods who live in the forest and take the form of giant animals such as boars, apes, and wolves. The mortal wounding of the boar god occurred at Lady Eboshi’s hands.

As the story unfolds, Ashitaka crosses paths with other notable characters. One is Jigo, a Machiavellian monk sent to Irontown by Japan’s emperor on a special mission. Another is the supreme deity of the countryside around Irontown, known as the Spirit of the Forest. Yet another is the titular princess, whose personal name is San (“Mononoke” means “spirit” or “monster”). San is a human woman raised as a wolf by the wolf-goddess Moro. As a result, San has renounced humanity and fights to protect the forest and the gods from Eboshi and the others in Irontown.

Amid all these competing and conflicting parties, Ashitaka tries to find some way to prevent further bloodshed and damage to the natural world. His efforts only gain in urgency as he begins to develop feelings for San.

Like all Ghibli movies, Princess Mononoke is visually spectacular. The lush green forests, fields, and mountains of Japan are rendered beautifully, as always. Character design is where the animators truly excel, though. In their drawing of the animal-gods and other supernatural beings, they succeed in creating characters who simultaneously look impressive and frightening.

We meet boar gods with enormous, grotesque snouts, tusks, mouths, and warts. Their elderly leader, Okkoto, is distinguished by his whitened fur and emaciated frame. Our first glimpse of the ape gods is at night, when they appear as a crowd of black silhouettes with glowing red eyes. Moro and her cubs (San’s “siblings”) boast white fur and massive toothy maws.

A clever detail of the animation is that the boars and wolves’ eyes are rendered with whites and pupils, like human eyes, while Yakul has opaque black eyes—the distinction subtly telegraphs the difference between intelligent supernatural animals and ordinary ones.

A less imposing, but still faintly unsettling, type of supernatural being is the kodama, spirits of the trees. The ghostly kodama resemble children and have heads that rattle mechanically when they shake them.

By far the best character in Princess Mononoke—indeed, one of the best characters in the whole Ghibli canon—is the Spirit of the Forest. Miyazaki takes time to introduce this being, carefully building mystery and anticipation. First, Ashitaka finds the Spirit’s tracks in the forest and then dimly glimpses the Spirit at a distance, through the trees, amid a haze of sunlight. Later, we see the form the Spirit takes at night, a colossal spectral figure known as the Night Walker.

Our first clear look at the Spirit comes about half-way through the movie. San has left a wounded Ashitaka in a sacred part of the forest, with the hope that the Spirit might heal him. After she has left, the Spirit approaches the unconscious Ashitaka. We see the Spirit’s feet, which are furry yet bird-like, enter the frame. As the Spirit walks, flowers and other vegetation spring up around him.

In a long shot, we see a creature like a great stag, but with a profusion of additional antlers, move toward Ashitaka. Then silence takes over the soundtrack as we cut to a close-up of the Spirit’s face, which is red and wizened and looks almost human.

The Spirit heals Ashitaka, yet we also see him wither a plant with a single breath. This being can give life and also take it away. As with Satsuki and Mei meeting Totoro at the bus stop, the encounter is essentially benign but has an air of danger and solemnity, as a human comes into contact with a being who is insistently, overwhelmingly Other.

Princess Mononoke has more to offer than spectacle, however. One of the movie’s great strengths is the complexity of its portrayal of the struggle between humans and nature (this is a strength it shares with Pom Poko, despite the two movies’ extreme tonal differences). While we are clearly meant to regard preserving the forest and its supernatural inhabitants—and by extension the natural world as a whole—as a worthy goal, Eboshi and the people of Irontown are not outright villains.

Rather, Eboshi is an intelligent, if ruthless, leader who has created a surprisingly just and humane society within the city she rules. Groups cast out of conventional society, such as former prostitutes and lepers, find employment, freedom, and some dignity within her arms industry. We get to know some of these people, as well as others in Irontown, such as a rather hapless laborer named Kohroku and his sharp-tongued wife, Toki. We are invited to sympathize with the city’s people.

Meanwhile, Moro, Okkoto, and the other nature deities are ambiguous figures. Their size and power give them a definite grandeur. Moreover, they have clearly been wronged by Eboshi and other humans’ destruction of their land, to say nothing of the physical suffering they endure from human weapons. Yet they are not kind or merciful beings, and they are largely indifferent to human lives and pain. As noted above, even the Spirit of the Forest, while radiating an unearthly serenity, can take life and can be quite destructive if unchecked. Like the natural forces they embody, the gods in this story are awesome but dangerous.

Princess Mononoke’s complexity carries through to Miyazaki’s carefully crafted resolution to this story. The battle between nature and human technology plays out as viewers in the late 20th and early 21st centuries know it inevitably must. The conclusion is tragic but not unremittingly bleak. By the end, much has been lost, but some good has been preserved and the worst possibilities have at least been delayed for a time. The movie’s final shot appropriately strikes a small, quiet note of hope. Again, I was reminded of Tolkien: “there was sorrow then, too, and gathering dark, but great valour, and great deeds that were not wholly vain.”

Lest I make the movie sound too solemn and weighty, I will hasten to add that Princess Mononoke also has some thrilling action sequences. I already mentioned the opening monster attack on the Emishi village. Another exciting sequence comes when San mounts a nighttime attack on Irontown.

Dressed in wolf skins and a painted wooden mask, she darts and jumps across the city’s rooftops, resembling both a human and animal at once. The accompanying sound design provides the marvelous detail of her feet clattering against the wooden roof tiles. As Eboshi and her people mount their defense against the intruder, we then get one of the movie’s single best shots: San appears atop a building, against a backdrop of smoke and firelight from the weapons foundry, like an avenging angel.

Gunfire seems to subdue San, yet she is soon up again and heading for Eboshi. This leads to a brief but forceful duel between the two women, with San wielding a dagger against Eboshi’s katana.

In the moment just before the duel, the camera assumes San’s perspective and we rush headlong toward Eboshi, as the latter prepares to fight.

The movie’s climax is yet another well-done sequence, which brings together all the major players, human and supernatural, in a final confrontation both with each other and a wholly new danger.

The English dub—which was written by Neil Gaiman!—is good, and the English-language voice actors are generally effective. Billy Crudup gives a committed, passionate performance as Ashitaka, making him the stalwart hero he should be. Claire Danes is fine, if not especially memorable, as San. Two stand-out performers are Minnie Driver as Eboshi and Billy Bob Thornton as Jigo. Those managing the dub wisely allowed the actors to use their natural accents, and that helps tremendously here. Driver’s British accent nicely conveys Eboshi’s aristocratic hauteur, while Thornton’s drawl gives Jigo a kind of folksy slyness.

While Princess Mononoke is a triumph, I must acknowledge that it is not perfect. In identifying the movie’s flaws, in ascending order of seriousness, I would first note that the plot is sometimes hard to follow. I couldn’t quite figure out what a group of hunters in boar skins, who appear in a late scene, were doing or what their role in the human characters’ plans were (they do look impressive, though).

A second, more serious, problem is the handling of the ostensible romance between Ashitaka and San. Whatever Miyazaki intended, their on-screen relationship is pretty much a vacuum. Little that we are shown occurring between them in the movie would believably lead to them falling in love.

San hates all humanity and hates Ashitaka specifically for intervening to stop her from killing Eboshi. She has enough conscience to refrain from killing him and even helps save his life. Later, because they share a common goal, they work together. All this is still a far cry from romance, however.

Ashitaka’s attitude is still more puzzling, as he seems to fall for San immediately. When he first sees San, we even get one of those tired “love at first sight” movie moments, where he stares at her while emotive music plays on the soundtrack. The clichéd scene is made doubly odd by how decidedly unappealing San looks at the time. She has just paused from helping her adoptive mother, Moro, who has been shot, by trying to suck the musket ball out of Moro’s open wound. The already pretty wild-looking San is spitting blood and also has blood smeared across her face, which seems an improbable context for a Some Enchanted Evening-style moment.

Apparently we are to understand that Ashitaka just really has a thing for blood-soaked, feral wolf maidens (which admittedly is such an oddly specific kink that I suppose I can’t blame him for pursuing her right away).

The final and biggest problem with Princess Mononoke is closely related to one of the movie’s strengths. Because this is essentially a tragic story that marches to its near-inevitable conclusion, little room is left for character development. Ashitaka, San, Jigo, and others remain much the same people at the end as they were at the beginning. San goes from loathing all humans to caring for Ashitaka but, even setting aside the unconvincing nature of their relationship, this is a fairly minimal change.

The only character who does change is Eboshi, who learns something about respecting nature. She is a secondary character, however, and one suspects she would have learned this lesson regardless of anything our hero Ashitaka does (although his efforts allow her to apply this lesson in the future). The largely static nature of the characters and the modest impact they have on each other’s actions makes the story a bit hard to relate to emotionally.

Still, none of these weaknesses are serious ones for me. I can even forgive the somewhat impersonal nature of the story because, as I see it, what Miyazaki has made in Princess Mononoke is fundamentally a myth (in much the same sense as Lewis defined the term in his Experiment in Criticism): a fantastical tale not about particular characters so much as larger concepts, in this case nature and humanity. Viewed in that light, I can appreciate it on its own terms.

I have already singled out the shot of San atop the roof, and that might well be my favorite image from the movie. The first close-up of the Spirit of the Forest would also be a contender for that distinction. Moreover, the movie is so overflowing with great visuals that innumerable shots stick in the memory.

My favorite humanizing detail comes in the opening battle between Ashitaka and the boar god/monster. After loosing his first arrow, as a warning, Ashitaka prepares to mount Yakul and give chase to the monster. As he does, he restrings his bow. The restringing is just a little throwaway detail, which very few people would have missed had it not been included. Yet the fact it was included is another sign of the care and dedication the Ghibli animators put into their work.

Because of how extraordinary this movie is, I feel justified in supplementing the usual favorite humanizing detail with two extra favorite details. In keeping with Princess Mononoke’s theme of giving due respect to nature, I must mention my favorite detail of how the natural world is rendered.

During an early scene, we see Ashitaka, Yakul, and Jigo traveling along the road. A nearby stream and its bank occupy much of the foreground of the shot. As the characters walk by, a crane reacts to the nearby noise and movement by flying off. Again, no one had to include this naturalistic detail, but it adds to the reality of the story’s world.

Last, I must mention a detail that is simply in a category all its own. During the movie’s climactic sequence, Eboshi confronts the Spirit of the Forest and aims a musket at him. The Spirit turns his head to look at her and his not-quite-human face smiles. As he smiles, the wood of Eboshi’s musket begins spontaneously to sprout green shoots and flowers. The moment perfectly captures the clash between Eboshi’s technological means of death and the Spirit’s abundant natural life.

In Princess Mononoke, Miyazaki and his team have created a work that is beautiful, powerful, and unforgettable. The movie is easily one of Studio Ghibli’s best works.

Leave a comment