Twice in a generation, Disney has tried its hand at the tale of Mulan; let’s see how these efforts compare! In this dual review, I look at Mulan (1998) and Mulan (2020).

The Ballad of Mulan is a Chinese poem, from the fifth or sixth century C.E., of a young woman who disguises herself as a man to fight in her father’s place as a soldier—and wins great honor for herself in the process. This story, at least in its bare outlines, would become familiar to American audiences when Disney did a feature-length animated adaptation in the late 1990s. More than 20 years later, Disney has returned to the Ballad of Mulan to produce a live-action version of the story, the latest installment in the studio’s current effort to remake its classic animated movies in (more or less) live-action form.

Slated for release in theaters at the end of this March before the Covid-19 pandemic put a stop to that, the 2020 Mulan was available for a while on the Disney+ streaming service for the hefty sum of $30. Being too cheap to spring for that, I am just getting to the movie now that it has become available as part of the regular Disney+ service. Rather than tackle only one movie version, I figured I would review both the animated original and the recent live-action remake.

The original Disney Mulan, directed by Barry Cook and Tony Bancroft from a screenplay by Rita Hsiao, Christopher Sanders, Philip LaZebnik, Raymond Singer, and Eugenia Bostwick-Singer, came at an odd time in the studio’s history. A decade earlier, and after their wilderness years following Walt Disney’s death, Disney had come roaring back as a maker of animated movies aimed at children with the Little Mermaid (1989). That movie launched the so-called Disney Renaissance, and other much-beloved movies, such as the Oscar-nominated Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), and the Lion King (1994) followed.

These movies reinvigorated the formula for profitable kids entertainment that Walt Disney pioneered (dubbed “the Midas Formula” by Edward Jay Epstein): a young protagonist goes on a magical adventure that features romance, at least one cute animal sidekick, and multiple musical numbers. For a while in the 1990s, Disney was on quite the winning streak.

By the start of the 21st century, however, the Disney Renaissance seemed to have run out of steam. The studio would have to do some creative re-tooling and depart from its traditional formulas (and fully embrace computer animation) before it regained the kind of success it enjoyed in the early 1990s.

Viewed in this context, Mulan is odd hybrid: an attempt to tell a different kind of story but somehow fit it into the old Disney formula. So, we get all the standard elements—romance, cute sidekicks, songs—and, in my judgment, they don’t work very well. The usual elements don’t fit with the story and the tone such a story requires. However, the original Mulan does boast a strong, memorably complex central character and some moments that capture the kind of epic quality this story should have.

To summarize the crucial plot points, our heroine is Fa Mulan, a young woman who is adept at horseback riding and schemes for managing her family’s farm. However, her outspokenness and general lack of social graces mean that she is not a promising future bride. (Or at least I think that’s meant to be her problem—the movie speeds through the early scenes of home life so quickly that precisely what makes Mulan such a misfit is left a bit vague.) Mulan’s oddity embarrasses her parents, much to her great sorrow.

Meanwhile, China is threatened by invading forces from the north (who are called “Huns” in the movie and vaguely resemble an historical people called the Xiongnu), and the emperor establishes a draft to muster the forces necessary to fight the invaders. Among those called up is Mulan’s father, the aging Fa Zhou. Because military service is a probable death sentence for her father, Mulan runs away from home and, as in the original poem, pretends to be a man and enlists in forces commanded by the young Captain Li Shang.

Among the standard Disney elements included in the animated Mulan, the biggest problem is Mulan’s chief General Issue Sidekick, a bumbling dragon named Mushu that is among the supernatural guardians of the Fa family. The spirits of Mulan’s ancestors attempt to send a guardian to watch over her during her time in the army and because of a Comical Mix-Up™ that guardian ends up being Mushu, despite his having disgraced himself after his incompetence previously caused one of the ancestors’ deaths. (Hilarity, folks!)

Part of the problem with Mushu is the vocal performance of Eddie Murphy, who does a loud, motor-mouth smart aleck shtick similar to Murphy’s own comic persona. Murphy is funny at times, but the whole tenor of the performance is so late-20th-century American and sometimes so at odds with the intended drama that it pulled me right out of the story.

The bigger problem, though, is that if you take much time to think about his behavior, Mushu is not lovable but completely awful. Mulan’s ancestors simply want the guardian to bring her home safely. However, Mushu, who doesn’t seem to have learned much from his past mistakes, deliberately keeps Mulan in the army and gets her to march off to war because he thinks making her a war hero will enhance his own standing with the ancestors and take away his past shame. This doubly risks her life, as she could be killed not only by the Huns but as punishment for impersonating a soldier, should she be discovered. Also, to get Mulan into battle, Mushu fabricates orders for Captain Li’s forces to march off to the war when they aren’t supposed to do so. And his antics later alert the Huns to the army’s presence, leading to a battle. Further, Mushu faces no real consequences for these life-endangering actions, apart from making a rather perfunctory apology late in the movie.

The Mushu character is the most prominent element of Mulan (1998) that should have been left out, but I can think of a few others as well. Too much of the movie, especially in the first half, is taken up with galumphing bits of slapstick and other alleged comedy: Mulan’s meeting with a matchmaker goes disastrously wrong; Mulan gets into a brawl with a Three Stooges-like trio of soldiers; Mulan’s attempt to bathe in a river leads to farcical complications, etc. These are the parts of the movie that had me checking how much longer the runtime was. I suppose the rationale for these moments is that they’re “for kids,” but if so I think the filmmakers underestimate kids.

The musical numbers are all fine. “I’ll Make a Man Out of You” in particular is a rousing song to motivate even the most apathetic among us (also, it gave us a fun music video with Jackie Chan). Still, I am not sure the movie strictly needed them.

The romance between Mulan and Li Shang is under-developed—they interact very little in the movie—but, in fairness, the movie as much as acknowledges this. They don’t get together at the end; we are simply given the possibility of a future relationship. That’s smarter than a lot of Disney movies.

So, those are the elements of the animated Mulan that don’t work well. What does work very well, however, is our heroine. Mulan as a character is portrayed with a subtlety that I appreciated.

Mulan’s motivations for risking her life in the army and the war are complicated. She certainly wishes to find a path for herself outside the traditional roles allowed to a young woman in her position, a path more in keeping with her own character. Her stronger motive, though, is devotion to her parents. She wishes to keep her father safe from the war and more generally wishes to make her parents proud. This sense of filial devotion is a somewhat unusual motive for a heroine in this type of adventure story, compared to the pursuit of more familiar goals such as realizing one’s dreams or finding romantic love. To me, it makes Mulan a more interesting protagonist.

Consistent with the central role concern for her parents plays, Mulan’s relationship with her father is the most interesting one in the movie. Fa Zhou is dismayed by his daughter’s unconventional personality and even scolds her at times, yet he is not fundamentally unkind to her. He tries to encourage and comfort his daughter in a key moment of distress.

Meanwhile, Mulan is solicitous of her father’s health and well-being even before the war looms as a danger. In an early scene, she provides him with the medicinal tea he needs—a gesture echoed later, after the draft call comes, when they tensely drink tea together. Her concern for his safety is emphasized in two wordless moments in which Mulan simply watches Zhou: first when he slowly, aided by a cane, walks across the courtyard of their family home; and later when he attempts to practice swordplay in his room—only to be betrayed by age.

Other important details about Mulan’s character are similarly established without words—a tribute to the filmmakers’ sense of visual storytelling. Several moments show us Mulan’s strong problem-solving and spatial reasoning abilities. To spread chicken feed around the yard, she ties an open bag of feed to the family dog and rigs up a bone in front of the dog to get him to run around, trailing feed. While walking through town, Mulan intervenes in two men’s board game to show one of them how to make a winning move. She passes a pivotal test during her army training by leveraging two heavy weights to her advantage.

The skills on display in all these little moments prepare us for an important scene later where Mulan figures out how to use the geography of her surroundings to win a seemingly hopeless battle.

I must mention another nice dialog-free moment. At one point, Mulan watches two little boys in her hometown playing soldier as they run past a little girl playing with a doll. Mulan smiles and shows heightened interest when she sees the boys. The obvious choice here would be to focus on the contrast between what is acceptable play for boys and girls, as well as Mulan’s reaction to that. Yet that is not how the moment unfolds: instead, the boys snatch the doll away from the girl and an irritated Mulan stops them and gives the girl her doll back. Rather than zero in on Mulan’s frustration with traditional girls’ roles, the filmmakers use the moment to highlight her basic sense of fairness and decency.

Beyond their effective building of Mulan’s character, the filmmakers also do well with some of the later dramatic scenes dealing with the war against the Huns. Once the slapstick and songs end, the movie gains in power and interest. The charred ruins of a village destroyed by the Huns is rendered in eerily effective animation. Silence and music is also used effectively in that same scene, as Li Shang deals with a tragic discovery (there is also a quiet moment with Mulan and a doll that echoes the earlier scene with the girl back home).

A battle on a snowy mountain slope is quite exciting and makes good use of both hand-drawn and computer animation techniques to give a sense of great hordes of soldiers sweeping along.

These scenes evoke the feel of the original poem’s lines,

She crosses passes and mountains like flying.

Northern gusts carry the rattle of army pots,

Chilly light shines on iron armor

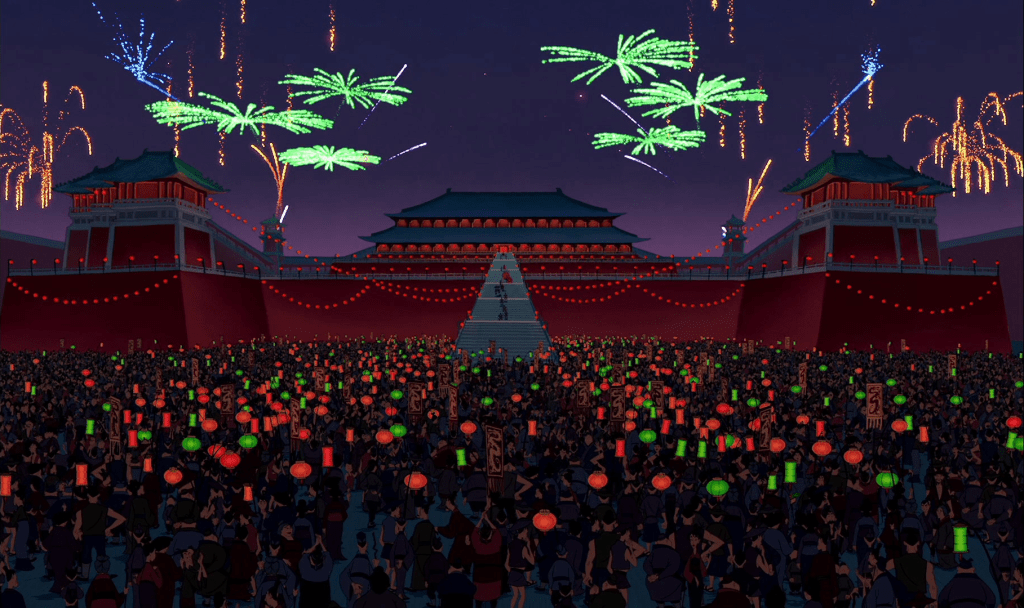

The final climactic sequence in the Imperial City also features striking animation. Again, different techniques are blended to create huge spaces filled with crowds, and we get an array of fireworks in this sequence, as well. (I also liked the detail of how Mulan uses a fan as an improvised set of nunchakus.)

A visual touch I appreciated was how, in keeping with the “Reflection” song, the filmmakers use the recurring image of Mulan’s face reflected on various surfaces: the polished ancestral tablets of her family; pools of water; and (twice) the blade of a sword. Shadows are also used well, as when Zhou’s faltering is conveyed by the sight of his shadow on the wall or when a great bird’s shadow soars across a battlefield below.

More than the filmmakers’ visual finesse, however, I appreciated how they paid off the movie’s best relationship in the final scene of Mulan and her father seeing each other again. This scene is Mulan’s emotional climax and was genuinely moving.

All the best elements of Mulan (1998) convey a sense of better, more powerful movie struggling to escape from the Disney formula. That other movie would have dispensed with the comedy and music and licensable characters and focused on the epic war story and the family drama that provides Mulan’s suspense and heart.

Disney had a second chance to make that other version of Mulan when they gave the movie the live-action treatment. How well does this new attempt at the story fare?

Mulan (2020), directed by Niki Caro from a screenplay by Rick Jaffa, Amanda Silver, Elizabeth Martin, and Lauren Hynek, gets a lot of things right. The movie corrects many of the flaws of the animated version, while still providing a strong main character and getting the central daughter-father relationship right. The re-make contains its own share of memorable moments and a great deal of visual flair. I would pronounce it good rather than great, though. This version still struggles against some of the limitations of the original.

For the most part, the new movie closely follows the original’s story but has streamlined it by leaving out almost all the elements that I found most tiresome in the animated version. Mulan (2020) is not a musical, has dramatically fewer attempts at comedy, and has reduced the romantic part of the story—already pretty minimal—to a mere hint. Above all, the movie contains no Mushu, and the screenwriters should win an Oscar for that alone. Mulan does have a magical protector sent by her ancestors, a phoenix. The filmmakers wisely give the phoenix only a few appearances, though, and do not have it voiced by an American comedian.

China is again threatened by invaders, this time a group known as “Rourans,” based on a real people of that name. The emperor’s draft again falls on Mulan’s family, here called the Hua family, and she secretly goes to war in her father’s place. A notable change, though, is the nature of Mulan’s misfit status and her gift as a soldier.

In the live-action version, Mulan is gifted with a special talent to channel chi, or life force, which makes her preternaturally fast, agile, and strong. This makes her naturally adept at fighting. In other words, Mulan is now essentially a Jedi. (Although since the concept of the Jedi was ultimately borrowed from Chinese Taoism by way of martial arts movies, I can’t really fault the movie too much for this.) The very chi sensitivity that makes Mulan a natural warrior, however, also makes her suspect to others, who are likely to label a woman with such abilities a witch.

Mulan’s gift of chi also leads to the creation of a wholly new character, Xianniang, an older woman with a similar gift who has been outcast as a witch and now serves Bori Khan, the leader of the Rourans. Xianniang uses her powers, which including shape-shifting as well as fighting, to help the Rourans infiltrate cities and otherwise triumph in battle. She does this despite the obvious contempt Bori Khan holds for a woman like her, as her exile from normal society leaves her with few other options.

I have mixed feelings about these changes. By giving Mulan magical abilities, the filmmakers provide a much clearer reason here than in the original for why she doesn’t fit into the conventional role expected of her. An early, disastrous encounter with a matchmaker, which parallels a scene in the original, this time involves Mulan unexpectedly displaying her abilities (although, as in the original, the encounter’s unhappy outcome is more the result of a bizarre series of accidents than anything Mulan does wrong). Still, I think I preferred the more cerebral version of Mulan’s abilities in the original.

Xianniang is an interesting idea for a character, a dark counterpart to our heroine who plays a crucial role in Mulan’s development while also getting her own appropriate arc. Nevertheless, the character doesn’t quite work on screen. She gets too little screen time and her interaction with Mulan is limited to only a couple brief scenes together. That isn’t enough to develop a convincing character. The great Gong Li cuts an impressive-looking figure in her black, armor-like dress and crown—which evoke Xianniang’s favored shape-shifting form of a hawk—but sadly she doesn’t get a wide range of emotional notes to play, mainly just being stern and menacing.

If Xianniang doesn’t succeed as a character, the far more important character of Mulan does, however. Yifei Liu gives a nicely restrained performance as our heroine. Mulan’s uncertainty about her place in life, as well as her later imposture, requires her to be guarded—yet at crucial moments Liu conveys the emotions beneath the surface.

Two scenes I especially appreciated were a pair of conversations that Mulan, in her masculine disguise, has with Tung, her commanding officer. In both exchanges, Tung’s words are rich with irony that he is not aware of but Mulan (and we) are. In close-ups during these scenes, Liu conveys a deep discomfort and shame through her eyes. I also liked a significant early scene when, in contrast to her later reserve, we see Mulan at greater ease and smiling more than at perhaps any other point in the movie: when she is riding on horseback alone. (This scene also includes a glimpse of a pair of rabbits that prompts an allusion to the original ballad.)

As in the original, filial devotion is at the heart of the new movie, and Tzi Ma captures the right mix of strictness and warmth as Mulan’s father Zhou. Also, like Liu, Ma finds the right undemonstrative approach to his character. One of the movie’s best scenes is a quiet conversation between father and daughter where they talk indirectly about the prospect of going to war without directly saying quite how they feel. Liu and Ma similarly do a fine job with the final reunion scene—although I must confess it did not pack quite as much of an emotional punch for me as in the animated version.

After Liu and Ma, the most notable performance is from Yoson An as Honghui, Mulan’s fellow soldier and (kind of? maybe?) future love interest. An has a low-key charisma that fits the role well.

If most of the main actors correctly underplay their roles, the movie’s visual style has no such restraints. The new Mulan is awash in vivid colors. This is most apparent in the characters’ costumes, which are a great treat to look at, from Mulan’s scarlet red cloak to the solid black worn by Bori Khan and his troops to the yellow, green, and gold robes of the emperor and his courtiers to the multi-colored attire (green, yellow, pink, red, among others) of many of the female characters.

The movie also boasts an array of impressive landscapes: the lush green fields of Mulan’s home village, the yellow desert and steppe, snow-covered mountains, and the vast Imperial City. Even locations we glimpse for only a moment are striking: I was particularly taken by the misty bamboo forest Mulan travels through on her journey to the army camp.

Caro and her cinematographer, Mandy Walker, have not just made Mulan beautiful to look at, though, but found an appropriate overall style for the movie. While no longer a musical, this movie is nothing if not operatic. The filmmakers are willing to go for big, dramatic imagery that heightens the larger-than-life feel of the story. To list just a few of the great images they create:

- Xianniang first emerging out the desert like a mirage

- Bori Khan and his men charging across the steppe—and Khan’s black scarf flying up into the air as they do

- A single figure walking down the immense steps of the imperial palace

- Hero shots of Mulan in red against a backdrop of white snow

If the animated original only sometimes captured the ballad’s feeling of high, solemn adventure, the new live-action version evokes that feeling more often.

The big moments are also balanced with some good small ones. When Mulan accomplishes a notable task that has taken her to the top of a mountain, the camera stays with her as she pauses and just stands there for a moment, contemplating her achievement. Later, in the seconds before a battle begins, she and Honghui exchange a brief glance and he gives her the faintest ghost of a smile.

For all its stylistic boldness and willingness to depart from the animated original, however, I think the new Mulan doesn’t go quite far enough.

One problem is that while it’s longer than the animated version (2 hours to the original 90 minutes), the movie still feels a bit rushed. I already noted the under-development of Xianniang and Mulan’s relationship with her. We similarly don’t get enough time between when Mulan joins the army and the movie’s climax to build real relationships between her and the other soldiers. As tedious as I found the animated version’s comedy with the bumbling soldiers, those soldiers at least emerged at memorable characters. Here, we get just a few brief scenes with her, Honghui, and the other soldiers, with a few comic snippets thrown in, and that’s about it. This robs the later scenes of wartime peril of some of the weight they should have.

The other problem is that while Mulan is a wartime story with clear martial-arts-movie influences (reinforced by the presence in the cast of such martial arts veterans as Jet Li, Donnie Yen, and Cheng Pei Pei), the action sequences are…well, kind of boring. Whether because Yifei Liu and some other cast members were not the most accomplished stunt fighters or (more likely) because of current Hollywood conventions, the fight scenes are chopped up with endless quick cuts that deny us a chance to see clear, compelling action. This approach is especially unfortunate in the final sequence in the Imperial City, where we get some inventive action scenarios—a battle in a tightly enclosed corridor; a duel amid precarious scaffolding—that are not filmed lucidly enough to reach their full potential.

Also, for a war movie, everything remains pretty bloodless, sanitized, and Disneyfied. Not a single recognizable comrade of Mulan’s dies in the movie. She never has to grieve over losing someone important to her, nor does she ever seem to grapple with the emotional weight of having killed other people. I am not demanding the filmmakers pile on the gore or give Mulan PTSD, but this relatively light-weight approach to combat works against the epic tone the movie is trying to strike. For a comparison, see Sergey Bodrov’s Genghis Khan biopic Mongol (2007), which also takes a stylized approach to violence yet still gives the story the high stakes of a world in which death is real.

My final verdict would be that I like both Mulan (1998) and Mulan (2020), but I also think both have serious flaws. The more recent version generally improves on the original, even as it doesn’t quite reach the heights it could have attained. I enjoyed it, though—and anxiously await the next remake Disney does in another 20 years.