Next in my Studio Ghibli retrospective, I look at a real gem in the studio’s catalog, Whisper of the Heart.

One of life’s few certainties is the presence of uncertainty. We face uncertainty about what we want to do with our lives, what will make us happy, who (if anyone) we may end up sharing our lives with, and even who we really are. Such uncertainties can trouble people of all ages but are perhaps particularly acute in adolescence.

Moreover, those of us, adolescent and otherwise, who might cherish artistic aspirations face an additional set of more specific doubts: Are we any good at our chosen art form? Can we truly realize our creative ambitions? Is the promise of creating art worth the work and sacrifice involved?

Yet, despite all these uncertainties and challenges, sometimes our artistic yearnings and efforts bear fruit, and the result is wondrous.

All these experiences—uncertainty, especially adolescent uncertainty, about life; the struggle to create; and the joys of art—are captured beautifully in Whisper of the Heart (1995), directed by the late Yoshifumi Kondo from a screenplay by Hayao Miyazaki. Based on a manga by Aoi Hiiragi, Whisper of the Heart doesn’t contain overt magic or fantasy. The parts of life it dramatizes, however, are quite magical in their own way while also being warmly human and relatable. I found this movie made me smile as often as My Neighbor Totoro, except this time my smiles were prompted not by delight but rather recognition.

The movie’s heroine is Shizuku Tsukishima, a Tokyo junior high school student. An imaginative girl, Shizuku spends her days constantly reading books, especially fairy tales, and dabbling in writing. As the movie begins, she faces entrance exams for high school, but she is less interested in studying than her own pursuits.

Shizuku experiments with writing alternative Japanese lyrics to the English song her class will sing at their junior high graduation: the John Denver folk song “(Take Me Home) Country Roads.” She is also intrigued by a boy’s name that keeps appearing in the check-out cards of her library books: “Seiji Amasawa.” Who could this boy be who reads all the same books she does?

The early scenes follow Shizuku through her daily routine, at home with her parents and older sister; and at school where she must deal with classes, exams, and the usual social complications, in this case counseling her best friend Yuko about the latter’s interests in various boys. She also must deal with a tall, laconic boy who likes to tease her and has a knack for turning up at inopportune moments.

Shizuku’s life takes a new turn, however, while she is riding the train around the city and encounters a large white cat with no apparent human owner. Intrigued by the stray cat, she follows it down various streets and alleys and ends up in an unfamiliar neighborhood, where she discovers an antique shop. The shop is run by a kindly old man, Mr. Nishi, who shares Shizuku’s fanciful cast of mind. The shop also contains a mysterious statue of an anthropomorphic, dapper cat whom Mr. Nishi calls “The Baron.”

These odd encounters set in motion a series of events that cause Shizuku to confront all the uncertainties and to ask all the questions I mentioned above. She continues to explore her writing and the rewards it brings. She also discovers [minor spoiler alert] that the teasing boy she keeps running into is none other than the Seiji Amasawa whose name she found in all those books. As a mutual romantic interest develops between her and Seiji, Shizuku makes a crucial choice to pursue her literary ambitions.

One of Whisper of the Heart’s great strengths is how deftly and thoughtfully it weaves together the twin plot strands of early romance and artistic yearning. Both are significant concerns in our young heroine’s life and closely reinforce each other. Seiji turns out also to be an aspiring artist, with his art form being violin making. When Shizuku meets him, he already seems quite skilled in this craft, but he is determined to do better. His goal is to travel to Cremona, Italy, to learn how to make violins professionally.

Seiji’s determination and assurance impresses Shizuku, but also intimidates her, since she feels so much less accomplished and more aimless in her writing and life. Partly inspired by his example and partly desiring to prove herself to this self-confident boy she likes, Shizuku sets out, during the months Seiji is away in Cremona, to write a novel. The novel will be a fantasy, like the fairy tales she loves, starring the dashing cat the Baron.

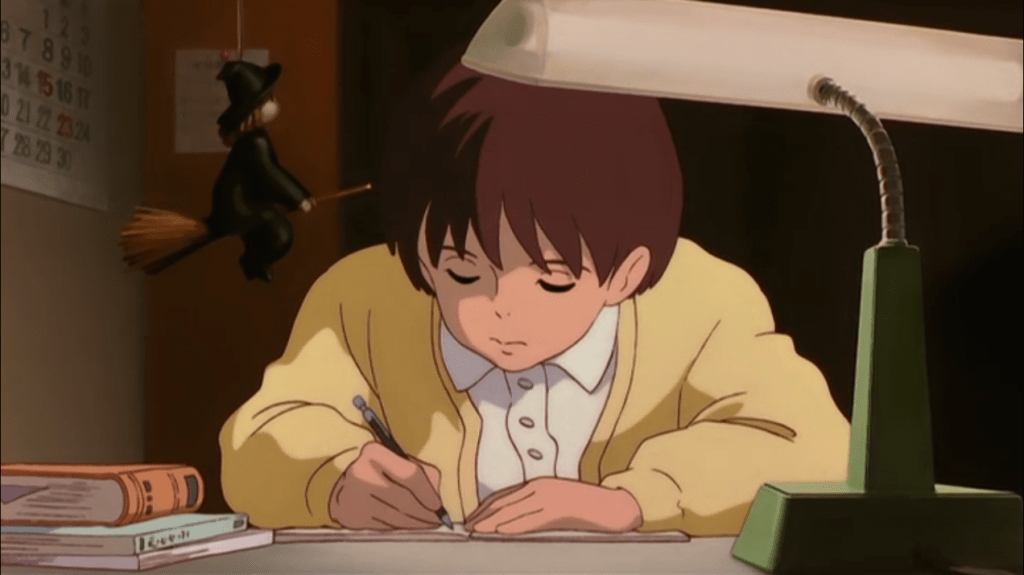

I love how the movie portrays the creative process. We see the excitement of initial inspiration (Shizuku narrates her unfolding story to herself as she runs down a hill), the necessity of discipline and a deadline (she forces herself to get the project done in two months), and how such work can dominate one’s life (she works around the clock, neglecting schoolwork and even regular meals).

I also love how Shizuku and Seiji’s respective artistic ambitions encourage their budding romance. A relationship based on similar interests and dreams, which have been established through careful characterization, is so much more believable and compelling than the usual lazy movie approach of “These two people are attractive and the leads so they must be in love!” These early adolescents are far more mature than many alleged adults on screen.

Several scenes stand out for how they memorably capture something about the characters, their relationships, or their art. At one point, Shizuku’s parents, concerned about her falling grades and distracted behavior, have a talk with her. Without giving many details on the novel-writing project, Shizuku insists on its importance and her need to pursue it. Her parents are puzzled by her obstinacy, but ultimately decide that if the project is that important to her, she should be free to focus on it. Shizuku’s father offers some sobering advice, though, on the dangers of following an unconventional path in life.

The scene finds the right, carefully measured tone for her parents to take, one that is neither harsh nor comforting. By portraying Shizuku’s mother and father as real human beings who aren’t rigidly strict but aren’t perfectly supportive either, the movie avoids falling into a clichéd or simplistic scenario. The scene also provides a valuable cautionary note on Shizuku’s dreams of a writer’s life. (She also seems aware at times of how her artistic pursuits may carry a price.)

While her parents are ambivalent about her artistic pursuits, Shizuku finds support from Mr. Nishi. Nishi, who is Seiji’s grandfather, becomes a mentor to Shizuku in her writing. Two key scenes between Nishi and Shizuku come at the beginning and end of Shizuku’s novel-writing project.

In the first scene, when she tells him of her book idea, Nishi encourages her and talks about the need for an artist to develop her talent through practice and effort. He shows her one of his shop’s curios, a seemingly ordinary rock that contains the mineral beryl inside. Nishi likens the process of honing one’s craft to bringing a precious gem out of a rock. This talk seems to help Shizuku, giving her the determination to pursue her project.

In the second scene, Shizuku brings Nishi her completed first draft and begs him to read it right away. After months of laboring over the work, she desperately needs someone else’s opinion on—and approval of—her efforts. He reads the manuscript while she waits, then finally praises the book. At which point the physically and emotionally exhausted Shizuku bursts into tears and confesses she thinks the book is bad, reciting all the flaws she sees in it. Nishi calms her down and reassures her that the book is good, just still a bit rough. It’s a touching moment.

Also, while Mr. Nishi plays a crucial role in Shizuku’s development as a writer and person, the filmmakers wisely don’t give him just a functional role. Like Shizuku’s parents, he is treated as a three-dimensional character, and we learn some of his own history and the regrets that tinge his life.

By far the best scene in Whisper of the Heart, however, which brings together the themes of love and artistry beautifully, is a scene involving Shizuku, Seiji, and Mr. Nishi. The lower level of Mr. Nishi’s store serves as a workshop where Seiji practices his violin making. One evening, he and Shizuku hang out in the workshop as Seiji works. Shizuku asks him to play something for her on the violin. Initially irritated, Seiji accepts the challenge and turns it around: Shizuku must sing along. He then begins playing “Country Roads” on his violin.

Taken aback at first, Shizuku hesitantly begins to sing along, using her own lyrics to the song. As Seiji plays and she sings, Mr. Nishi and some friends arrive at the workshop. Not missing a beat, they pick up musical instruments of their own from around the shop—Mr. Nishi plays the cello, his friends the tambourine, flute, and mandolin—and join in. Shizuku continues to sing, with Seiji and the others each doing their own instrumental solos.

The whole impromptu performance is an inexpressibly joyful moment. The spirit of the scene recalled for me Gene Kelly’s raptures amid a downpour. The underlying feelings are complex, though. The performance reflects romance, yes, but also the thrill of creativity and being part of a creative community. Moreover, Shizuku’s personalized lyrics are a frank admission of vulnerability: they deal with her uncertainty, her fears, her loneliness. The scene blends many different emotions.

Kondo and his animators also do an excellent job in this scene of portraying Shizuku’s changing reactions. We see Shizuku’s alarm at being asked to sing, then her alarm growing as she recognizes the song Seiji is playing, then her resolution to plunge ahead, then her growing confidence as she keeps singing and the others join in. Standing stiffly at attention at the start, she is at ease by the end, swaying and clapping along. It’s a lovely bit of animated “acting.”

Whisper of the Heart’s slice-of-life story of ordinary people dealing with real-world situations might not seem to allow as much room for memorable visuals as Studio Ghibli’s more fantastical movies. Yet Kondo and his animators find plenty of room for creative animation. They depart from strict realism at times, as when they portray scenes from Shizuku’s unfolding novel of the Baron’s magical adventures. These glimpses into our heroine’s imagination include backgrounds created by the surrealist artist Naohisa Inoue and feel like foretastes of some future Ghibli movie (as, in a sense, they would prove to be). We also get stylized depictions of Shizuku’s and Nishi’s dreams.

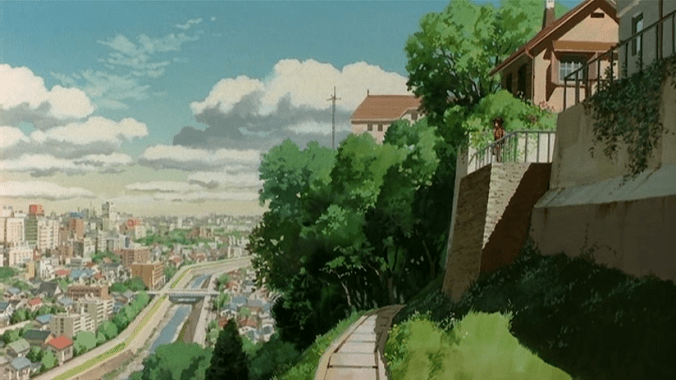

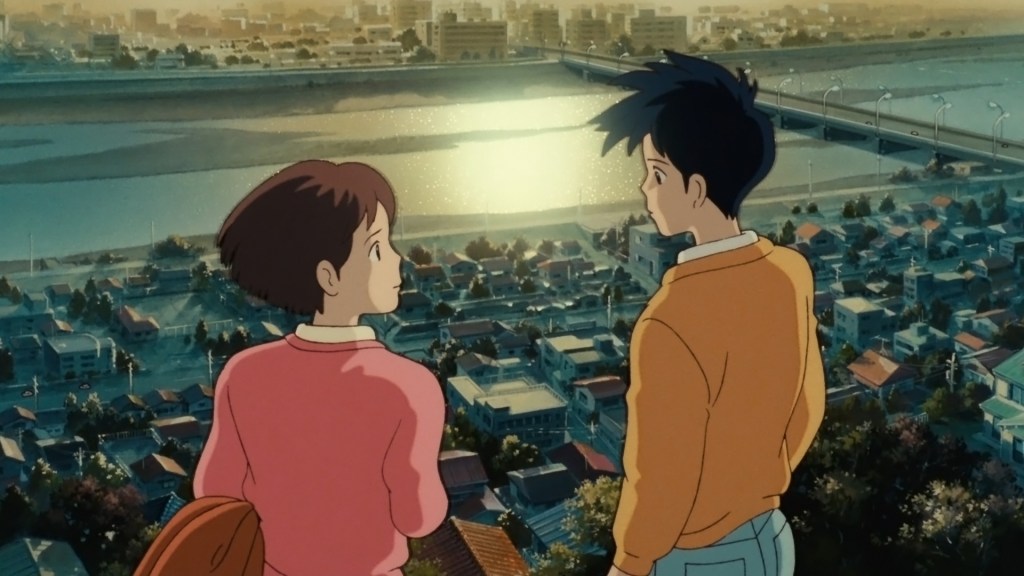

The aspect of the animation that made the biggest impression on me, however, was not primarily the forays into fantasy but the way in which the filmmakers portrayed then-contemporary Tokyo and its suburbs. While I cannot say for certain (never having been to the city), the movie feels like a bit of a love letter to Tokyo. The hilly terrain Shizuku must traverse in her daily routine gives her—and us—many stunning views of the cityscape. Indeed, it’s a running visual motif that she and other characters keep finding themselves looking down on the city, in sun and rain and at different times of day. This motif turns up most memorably in the movie’s gorgeous final scene, as Shizuku and Seiji look down to watch the sun rise over a still-misty city.

Moreover, having this rather idyllic-looking city serve as the backdrop for our imaginative heroine’s sometimes serendipitous adventures makes Shizuku’s urban environment seem as magical as the countryside does in Totoro. Watching Shizuku pursue the white cat down an alleyway made me think of Mei pursuing the miniature Totoros through the forest underbrush.

The movie’s English dub works well. Released in 2006, the dub features various familiar young American actors of the early 2000s as the adolescent protagonists. Brittany Snow is quite good as Shizuku, conveying the character’s many emotions with total sincerity. David Gallagher hits the right notes as Seiji, making him sometimes aloof yet basically good-hearted. Ashley Tisdale is amusingly histrionic as Yuko. The adult voice actors are also effective, especially Harold Gould, who conveys immense warmth and kindness as Mr. Nishi.

Also (dare I say it?), I think the English dub improves slightly on the Japanese original in its treatment of the final scene. The English dialog emphasizes the equal importance of Shizuku and Seiji’s artistry and also gives Shizuku an absolutely perfect, wry response to a big question from Seiji.

My choice for favorite image in Whisper of the Heart is a great shot that blends together Shizuku’s novel with her real life. We see the novel’s scene of Shizuku and the Baron flying through the sky, headed toward the horizon. Then the camera tilts down to reveal, at ground-level, the real Shizuku running excitedly down a hill as she makes up the story. The shift from imagination to reality within a single shot perfectly captures her state of mind, while the sight of (once again) the city spread out before the running girl reflects the vistas that her new creative endeavor has opened before her.

The movie abounds in humanizing details, so I have an embarrassment of riches to choose from there. I think my favorite detail comes during a brief scene when Shizuku is sitting in her room one night reading. The book, which she checked out from the library earlier, is a work of history, but we have no additional information about it. Yet as Shizuku reads the book, the movie cuts to a close-up of her face and we see that her eyes are filled with tears. What has she read that has moved her so? We never find out, and the movie never returns to the history book or this moment. Yet it’s a nice little example of what can happen between a book and a sensitive reader.

I must acknowledge that Whisper of the Heart will always be remembered not merely for its own merits but for its association with real-world tragedy. The director, Yoshifumi Kondo, would never make another film. He died three years later, at only 47, from a ruptured aneurysm. That anyone should die so young is heart-breaking enough. That Kondo was never able to apply his tremendous talent to making additional movies only deepens the loss.

Kondo was able to make one truly great movie, however, one which captures the struggles and hopes of so many artists. Whisper of the Heart‘s portrayal of the artist’s path has the power to inspire many either to follow that path for the first time or to renew their commitment to following it. A work like that is an extraordinary legacy to leave behind.

Leave a comment