Next in my Studio Ghibli retrospective, I turn to Pom Poko.

Pom Poko (1994), written and directed by Isao Takahata, is a tale of magical tanuki, or “raccoon dogs” (a canine species native to East Asia that resembles the North American raccoon). The movie is set among a community of tanuki living in the forest of Tama Hills, an area outside Tokyo. Their way of life is threatened by humans gradually destroying the forest to build a suburb. In response, the tanuki launch a desperate effort to save their wooded home from the human development.

This premise is about as standard as the storyline of a cartoon about anthropomorphic animals can get. How the story plays out, however, is anything but conventional. What Takahata and his animators created in Pom Poko is a series of bizarre situations and an array of hallucinatory images that are clever, visually inventive, darkly comic, and rather sad. What they did not ultimately create, however, is a satisfying full-length movie.

In their campaign for their homeland, the tanuki rely on their preternatural ability to change form and assume the likeness of human beings, inanimate objects, and all sorts of fantastical creatures. The tanuki’s magical abilities are not the movie’s invention but part of Japanese folklore, in which magical tanuki play a significant role. Indeed, I learned from a bit of subsequent online reading that Pom Poko is rich with elements from Japanese mythology and folktales (most of which initially went over my head). The movie is thus a kind of modern-day updating of traditional stories, much like how western artists might re-tell European fairy tales with modern settings or sensibilities.

The movie’s title, in case you were wondering, is a Japanese onomatopoeia for the drum-like sound tanuki make when trying to intimidate others. The drum beat is created by beating on their bellies or other parts of their anatomy (more on that later).

We see the tanuki employ physical sabotage against the suburban construction, with some tanuki even advocating violence. Above all, they try to terrify the human workers and residents into leaving. Our canine heroes also seek out, from other regions of Japan, tanuki who are masters of shape-shifting in the hopes they can provide the magical powers necessary to win the struggle.

The movie’s two biggest strengths are the visual inventiveness with which the tanuki’s shape-shifting is portrayed and the complex, nuanced approach the filmmakers take to this material.

Even before we get to the shape-shifting aimed at intimidating humans, Takahata and his animators portray no fewer than three different forms the tanuki take just in their ordinary lives. Sometimes they are drawn quite naturalistically as four-legged animals that resemble real-life Japanese raccoon dogs. Presumably because this is how they appear to humans, the tanuki often take this form when lurking at roadsides or in other human-dominated settings.

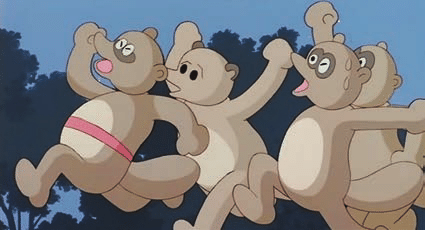

At other times, when dealing just with each other, they take the form of dumpy, two-legged creatures resembling overstuffed teddy bears. This seems to be their “default” state.

More rarely, in moments of extreme vulnerability (whether because of emotion or external circumstances), the tanuki become very simply drawn and almost doll-like.

The filmmakers also do a good job of finding details or features to distinguish the large cast of non-human characters from each other. Often the characters wear some simple article of clothing or have fur that resembles a mustache or glasses or otherwise have distinguishing characteristics that help us to keep all the tanuki straight. Community matriarch Oroku wears a red kimono and traditional hairstyle; the warrior Gonta is a hulking fellow with a red vest; dashing young Tamasaburo wears a blue scarf and sports a tuft of white fur on his head; and so on.

However, those already familiar with Pom Poko know that so far in my discussion of the character design I have avoided an elephant in the room (if that is precisely the metaphor I want to use). To a non-Japanese audience, the most striking aspect of the tanuki is that, in contrast to the bowdlerized way most anthropomorphic animals are drawn in cartoons, the male tanuki are drawn with large, prominent testicles.

You could call the characters “anatomically correct,” but that wouldn’t quite be right, since biological accuracy was definitely not the standard here. In keeping with the tanuki’s magical nature, the males’ testicles can take on whatever size or shape their owners wish. One aged tanuki turns his testicles into a giant rug. Another transforms his into a ship capable of carrying him and a crowd of fellow travelers. A squad of warrior tanuki mounting an aerial assault expand their scrotums to great size to serve as parachutes. (As Dave Barry would say, I swear I’m not making this up!)

All this is quite odd to an American viewer, but, like much of the movie, is in keeping with how tanuki are traditionally portrayed in Japanese art. More to the point, this detail of the male characters is just that: a detail that doesn’t really have much to do with the movie’s plot or themes. If you can adjust to the oddity, you will find it has very little impact on your experience of the rest of the movie.

The animation in Pom Poko really takes off when the tanuki start taking on forms other than their natural ones, to frighten and impress the humans around them. A scene in which the tanuki scare a security guard by initially pretending to be human only to remove their own faces is a mini-horror movie, as well as a riff on the mythical figure of the Noppera-Bo.

When some wizened master shape-shifters travel across Japan to help our protagonists, they travel in human form. Their human alter egos don’t look like ordinary people, though, but geriatric wizards/hippies/superheroes—and that description probably doesn’t do the character design justice.

The movie’s most spectacular sequence is when, after having been mentored by the shape-shifting masters, the tanuki stage a supernatural parade in the middle of the human Tama Hills community. They become foxes, skeletons, a great dragon, and a variety of other grotesque-looking mythical creatures. The parade is creepy and funny and also contains a few Ghibli Easter eggs.

Takahata and company even include a variant of that hoary old movie cliché, the drunk guys reacting to something fantastical, that manages to be amusing.

How the humans react to all this and the consequences of the tanuki’s actions is handled with the complexity that is Pom Poko’s other great strength. An aspect of the filmmakers’ subtle touch that I appreciated is how they don’t turn the struggle between tanuki and humans over Tama Hills into a simple good vs. evil battle. The movie contains no obvious villain—we never see some greedy, heartless tycoon plotting to destroy the forest. The human residents of the unfolding suburb and the construction workers building it are portrayed sympathetically as just ordinary people trying to live their lives. Some humans are greedy, but those characters come across as more buffoonish than evil.

Moreover, the various tanuki are not unambiguously good characters. We see how they are gluttonous, lazy, and often at odds with one another. While their basic goal of preserving their homeland is a good and honorable one, the methods they use in pursuit of this goal are often less admirable. The scaring of the security guard and certain other humans comes across as outright cruel. Worse still, when Ganta and other warrior tanuki attempt to sabotage a construction site the movie’s pulls no punches in showing us just how destructive they are: three human workers end up dead because of their antics. This dark turn of the plot is soon followed by a morbidly comic twist: after Ganta and his fellows return to the tanuki community in triumph, a crowd of agitated tanuki subsequently end up trampling Ganta, breaking his bones and leaving him bed-ridden for a year.

Beyond the morally murky nature of the tanuki’s campaign, the movie also shows the animals as having a certain ambivalence toward humanity. The tanuki may hate what humans are doing to their forest, but they like certain aspects of human society. Humans have developed chant-like songs about tanuki, and the tanuki have developed a custom of reciting the next verse when humans sing to them, in a call-and-response pattern. During one simple, oddly affecting scene, two young tanuki talk about humans’ violent nature and the harm they have done—but also admit they kind of like human songs.

Above all, the food-loving tanuki enjoy stealing human cuisine. In another scene, a group of tanuki rant and rave about how much they hate humans and want to wipe them out, only for someone to point out how delicious tempura and other human foods are. After discussing the matter further, the group agrees that maybe humans aren’t so bad and they should keep at least some of them around to make food. This scene plays rather like a canine version of the “What Have the Romans Ever Done for Us?” bit from Life of Brian.

The love-hate relationship between humans and tanuki extends to some tanuki having the ability to assimilate. They can use their shape-shifting power to transform into humans and live almost their whole lives within human society. Constantly taking a form other than their own requires considerable effort, however, and Pom Poko explains (in a nicely cheeky touch) that dark circles around the eyes of fatigued humans are really their underlying raccoon dog natures coming out.

A running theme is how in the modern age humans no longer recognize tanuki as creatures with magical abilities but view them simply as beasts. Thus, even when the tanuki stage frightening or fantastical displays of their powers, it has a minimal effect on the destruction of the forest. The humans mostly find ways to explain away the strange events in Tama Hills. The most striking example of this comes after the tanuki’s grand supernatural parade through town. As people try to sort out what happened, the owner of a local theme park grabs the media spotlight and claims the parade was all a promotional stunt for his new business. Whatever impact the tanuki expected to have on human behavior is lost as a result.

Pom Poko does a generally good job of juggling the comic and tragic elements of the story, finding a tone that is the right blend of whimsical and pessimistic and reminded me of Douglas Adams (although Takahata and his team show a basic compassion toward their characters that the notoriously heartless Adams lacked). The struggle between tanuki and humans eventually leads to an appropriately bittersweet conclusion.

The impressive visuals and complexity of the material could have made Pom Poko a great work…if it had been about an hour long. The movie is actually over 100 minutes long, however, and that is where the problem arises. For all their skill, the filmmakers just don’t have enough actual story to sustain a full-length movie.

Humans’ obtuse refusal to recognize the tanuki’s supernatural abilities, while thematically significant, also means that the plot cannot really advance. As the movie continues, it becomes quite static: tanuki stage a stunt to scare humans; the stunt has some minor success in holding up further construction; then humans forget about the incident and continue their environmental destruction; the tanuki argue about what to do before trying another stunt; repeat.

Moreover, Pom Poko is padded out with sub-plots that never go anywhere. Because the human construction has shrunk the woodlands available to them, the tanuki resolve to limit their population by not mating. They manage to do this for one springtime but by the next spring they give in and have a baby boom. This turn of events doesn’t have any impact on the story, though, apart from making the tanuki’s situation somewhat more difficult than it already was. The viewer is left wondering why the movie spent so much time on this story thread.

Later, we are introduced to another magical, shape-shifting animal and this new character promises a new twist in the plot. Yet this sub-plot just ends in an absurd comic scene and never affects the larger course of the movie. And these are only two examples of narrative dead-ends within Pom Poko. A viewer might be forgiven for eventually getting impatient.

If I had to pick a favorite image from Pom Poko, I would not choose any of the supernatural transformations or dream-like creatures but a very simple shot of a cherry blossom tree framed against the sky. As always, Studio Ghibli excels in depictions of the natural world, and the forest landscapes are beautiful, with this image being a stand-out.

As for favorite humanizing (or “raccoon dog-izing”?) detail, I am fond of a moment from an early scene where the tanuki steal an abandoned TV so they can learn about humans. As they walk off with their loot, one of the scavenging tanuki takes the TV’s antennae and places it on his head, playfully creating his own “rabbit ears.”

In evaluating Pom Poko, I don’t wish to sound overly negative. I give Takahata a lot of credit for trying something so different from his previous two Ghibli movies. Even if he couldn’t quite pull the elements together into an absorbing, satisfying feature, parts of the movie work quite well. That is a worthy accomplishment in itself.

Leave a comment