I continue my Studio Ghibli retrospective with a look at one of the more obscure entries in the studio’s output.

Ocean Waves (1993) stands out among Studio Ghibli movies for several reasons. It was Ghibli’s first (and, until the forthcoming Earwig and the Witch, only) TV movie. Directed by Tomomi Mochizuki, Ocean Waves was the first Ghibli feature not directed by Hayao Miyazaki or Isao Takahata. Written by Kaori Nakamura and based on a novel by Saeko Himuro, the movie is also unusual for not containing any magical or fantastical elements. While even the ostensibly realistic drama Only Yesterday included ghost-like memories and a fantasy sequence, Ocean Waves sticks to a doggedly naturalistic approach to its story. Last and most sadly, Ocean Waves differs from most other Ghibli movies in being not very good.

To be clear, I didn’t find the movie egregiously bad. It was free of anything I would consider cringe-worthy (well, mostly; I will get to one notable exception). Yet I also found it fairly boring, because the filmmakers consistently chose to focus on the least interesting aspects of a promising story. Despite the movie being only 70 minutes, I found myself wondering how long it would be until it was over.

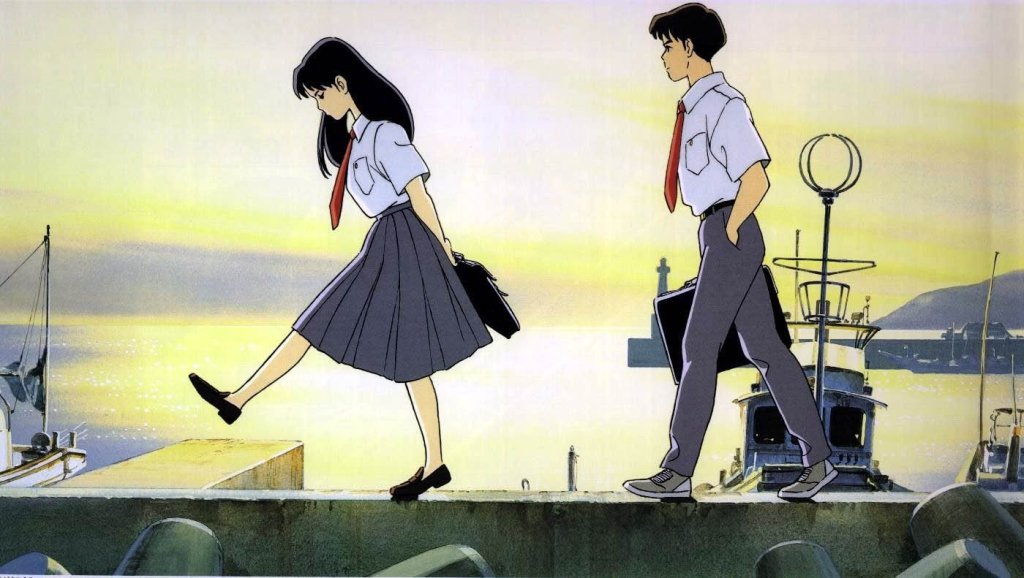

Ocean Waves looks at a trio of high school students in the city of Kochi. Rikako is the new girl at the school, having just moved to town from Tokyo following her parents’ divorce. She attracts the attention of a boy at the school, Yutaka. Meanwhile, Yutaka’s friend Taku is faced with a messy situation as he is drawn into Rikako’s complicated life and perhaps begins to develop feelings for her as well. All this is presented in flashback, as recalled by Taku, who narrates the movie. The framing device for the flashback is Taku, now a college student, returning to his hometown for a high school reunion.

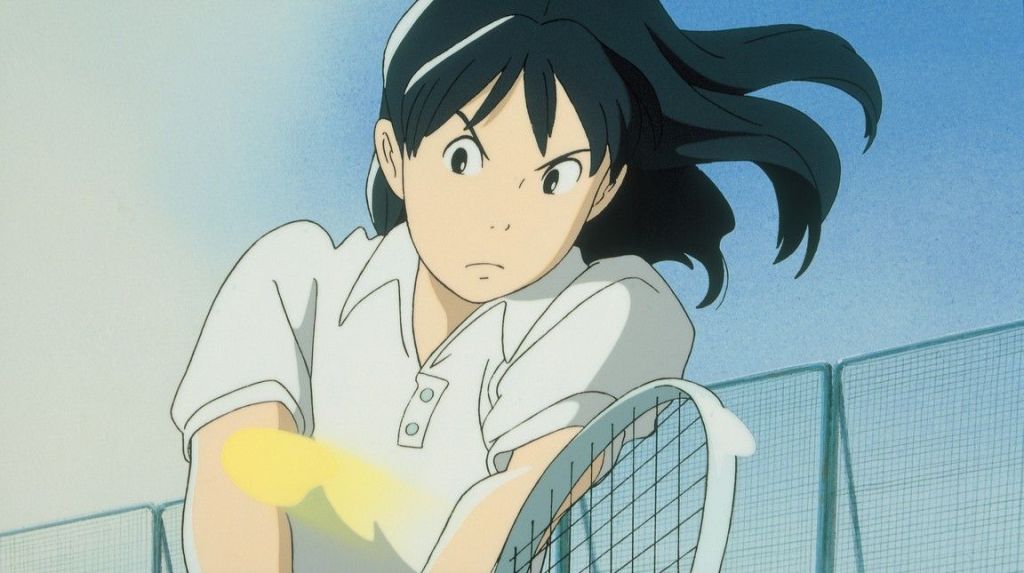

To give credit where it’s due, the movie finds some fresh angles on its very familiar romantic-triangle plot. The most surprising and striking aspect of Ocean Waves is how Rikako, far from being some fantasy “dream girl,” is a quite nasty person. She is good-looking, yes, and talented, both academically and athletically. Yet she is also spoiled, selfish, dishonest, and manipulative. Her first significant interaction with Taku is during a school trip, when she cons him out of a very large amount of money—and then she does the same to Yutaka. She gets Taku to pose as her boyfriend so she can impress an ex. She rejects Yutaka in a needlessly insulting way. And so on.

We are meant to understand that Rikako is a deeply troubled and angry young woman, wounded by her parents’ separation and her relocation to a new city, as well as the inevitable loneliness of attending a new school. The most interesting moments in Ocean Waves are ones that explore Rikako’s painful personal and family situation. The scene with her, Taku, and her ex provides some well-observed comedy in its contrast between Rikako and the ex’s smarmy, superficial friendliness and Taku’s growing irritation. Another scene, where Rikako visits her affluent father and encounters his new girlfriend, is a quiet, sympathetic study in embarrassment. Later, a distraught Rikako turns up at a hotel where Taku is staying, to seek comfort partly from him but mainly from his room’s minibar. The encounter seems likely to move either in a romantic or potentially creepy direction but ultimately has a more mundane, funny resolution. (Taku’s narration here explicitly calls out our expectations, as he observes “The whole thing was starting to feel like a bad soap opera.”)

These parts of Ocean Waves work well, and if the movie had been a family drama about Rikako’s unhappy situation, then it might have been pretty good. As it is, however, the movie is about the romantic triangle among Rikako and the two boys, and this part ultimately falls flat.

One problem is that the Rikako’s unpleasant behavior, while it makes her an intriguing character, also raises the question of why either Yutaka or Taku would be interested in her. Certainly even an adult, let alone a teenager, can fall for a toxic person. Nevertheless, the movie does very little to sell us on Rikako’s appeal—she doesn’t come across as charming or otherwise winsome—or to explore why either boy would allow her to string him along. I suppose the answer is meant to be her physical attractiveness, but that isn’t terribly interesting dramatically.

Moreover, the two boys are underdeveloped as characters, with our narrator, Taku, being the more ill-defined of the two. I cannot think of what Taku’s distinguishing characteristics are meant to be, apart from being hapless in the face of events. For example, he sometimes seems concerned about Rikako’s well-being and remarkably forbearing over her bad, demanding behavior. Is this an expression of a kind heart? A sign of a weak will? Just another reflection of his growing infatuation with her? I am not certain, because the character doesn’t register strongly enough for me to know what kind of person he is supposed to be. The movie seems to rely on his status as the point-of-view character to stand in for an actual personality.

Yutaka fares a little better, partly because we aren’t privy to his thoughts, and thus he comes across as somewhat enigmatic. Also, his active pursuit of Rikako makes him a more decisive character than Taku. Still, we don’t learn much about him. Taku tells us he admires his friend’s foresightedness, yet for the most part the movie doesn’t show us Yutaka doing anything especially foresighted or intelligent.

Ocean Waves’ central characters, especially the two boys, suffer from a writing problem certain movies can have that Roger Ebert identified many years ago. The characters seem concerned almost exclusively with the situations presented by the movie’s plot. Apart from Taku and Yutaka showing a bit of rebelliousness toward school authorities early on, neither of them appears to have any personal beliefs, interests, or passions. They are just preoccupied with their tangled relationships with Rikako and each other. Such limited characterization predictably produces less textured characters.

Worse, as the movie progresses it starts to descend into precisely the kind of “bad soap opera” Taku poked fun at earlier. Let me offer some advice to screenwriters everywhere: having one character in a drama hit another can be shocking and powerful if it happens once. When characters repeatedly hit each other in multiple scenes, however, then you are moving away from “powerful” and into “melodramatic” or even “unintentionally funny.” An overwrought, eye-rolling scene of this kind is a low point for Ocean Waves.

Notwithstanding the weak script, Mochizuki and his team do a good job animating the movie with Studio Ghibli’s customary knack for detailed, memorable visuals. In an early scene in a school art room, both the replicas of Classical statuary decorating the room’s walls and the late afternoon sunlight coming in through the windows are nicely rendered. I liked the glimpses we get of the restaurant where Taku works after school as a dishwasher: the gruff, hulking cook who carves up a vividly blue fish; and another cook (“a former gang member,” Taku says) who crouches in the alley behind the restaurant during his smoke break. We get a haunting shot of the sea at night-time, with the only illumination of the seascape the flashing light of a ship on the water. The animators also repeatedly do a good job with reflections: students reflected as they walk along polished school floors; Rikako faintly mirrored in a window; blue sky and clouds reflected in a pool (the fallen yellow leaves in the pool add an appropriately melancholy touch).

All the visual skill on display in Ocean Waves, however, paradoxically emphasizes the movie’s central weakness. The visual details are just so much more interesting than the main plot. The care taken with peripheral characters exemplifies this problem. I liked how in street or crowd scenes the “extras” moved or had significant little moments. During a school scene, we see a small child tarrying outside the school only for his mother to take his hand and lead him along the sidewalk. While Taku and Yutaka walk through the city, I was distracted by the man flipping through a magazine at a newsstand in the foreground. These bit players display a vitality lacking at the movie’s heart.

My choice for favorite image from the movie is a funny and poignant shot from the scene of Rikako and Taku’s awkward visit to her father’s. As she goes up to her father’s apartment, Taku is left waiting in the lobby. While he sits on a couch there, footsteps on the stairs signal the father’s irritated girlfriend, a stylish, sunglasses-wearing woman, exiting the building. We then get a shot of Taku staring stiffly ahead, studiously trying not to notice as the girlfriend sweeps past behind him.

My choice for favorite humanizing detail is a throwaway moment with one of those bit players. While Taku is waiting on a plane before take-off, we see in the background a little boy peering out the airplane window until a parental hand pulls him back. It’s a moment of recognizable behavior that brings a smile to my face.

Toward the movie’s close, a hint of an interesting theme emerges. At the high school reunion, one woman reflects about how she disliked Rikako when they were in school together but seeing Rikako now makes her feel nostalgic. Being out of the enforced communal life of school has softened her attitude. The comment is insightful and relatable and suggests yet another movie that could have been made from this material. The curious environment of high school and the love-hate relationships that can evolve among people who must spend their formative years together is a fruitful theme for drama. I would have liked to see that version of Ocean Waves.

Leave a comment