In this review, I look at two animated movies, made more than 30 years apart, that each follow a young person struggling to survive amid war, including nuclear devastation.

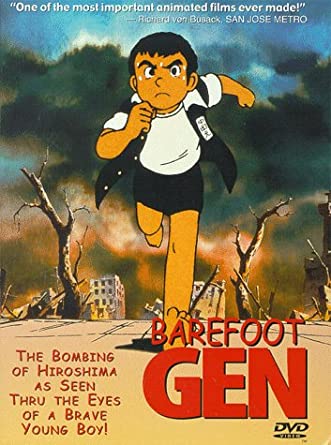

The world recently marked the 75th anniversaries of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th and 9th, respectively. To remember these cataclysmic events, I decided to watch two Japanese movies that deal with the Hiroshima bombing: Barefoot Gen (1983), directed by Mori Masaki, and In This Corner of the World (2016), directed by Sunao Katabuchi.

Barefoot Gen is based on a manga series by Keiji Nakazawa, who survived the Hiroshima bombing when he was a child. The movie tells the story of Gen Nakaoka, an elementary-school-age boy who lives in Hiroshima. Gen is the second child of a poor man who makes a living as a farmer and cobbler. Gen has an adolescent sister, Eiko, and a toddler brother, Shinji, while their mother is pregnant with a fourth child when the movie begins.

Roughly the first third of the movie is devoted to scenes of Gen’s life in the summer of 1945. We witness the family’s poverty and their struggle, amid rationing and other hardships of the Second World War, to obtain enough food. Keeping the mother and her unborn child nourished and healthy is a particular concern. We see other effects of the war on daily life: the movie begins with the Nakaoka family huddled in a bomb shelter to avoid an American air raid. Later, we see a small, flag-waving parade of people send a soldier off to the war.

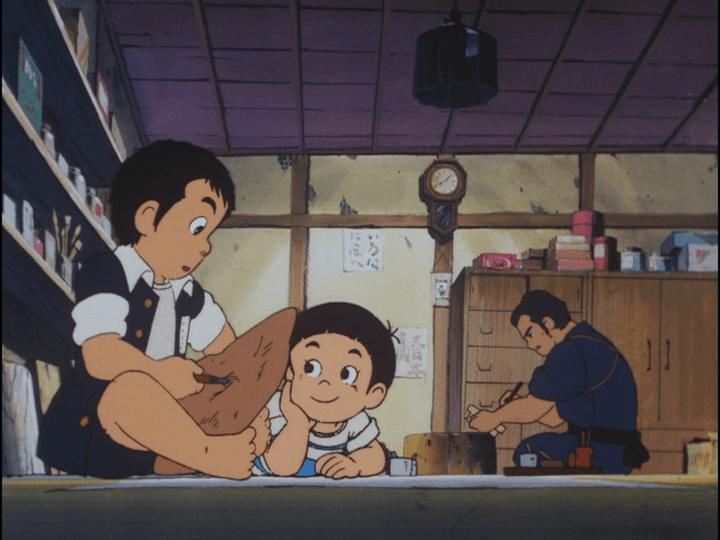

Despite these hardships, Gen behaves likes an ordinary rambunctious boy, running around town and fighting with his younger brother. One memorable episode involves Gen and Shinji trying to get food for their mother by stealing a fish from a wealthy man’s pond. In another, touching, moment, Gen and Shinji huddle close to their mother to feel their sibling kicking inside her. Although they can only sketch in the characters and their relationships, these warm early scenes nevertheless provide a sense of this family and how much its members love each other. Meanwhile, Gen and Shinji’s antics and bickering prevent the family scenes from getting too treacly.

Perhaps because of its age, the movie’s animation might seem unimpressive to contemporary viewers, at least at first. Compared to the vivid, detailed visuals of recent anime, Barefoot Gen’s imagery looks less polished, with relatively muted colors and rougher draftsmanship. The design of Gen and Shinji is similar to what you might expect in a newspaper cartoon strip. The movie even uses some comic strip effects: when Gen fights another boy, their brawl is enveloped in a huge cloud of dust with stars flying out of it; when the other boy cries, fountain-like springs of water come out of his eyes.

Despite these superficial limitations, though, Masaki and his animators show considerable visual inventiveness throughout the movie. While much of Barefoot Gen unfolds in a series of fairly static long shots, medium shots, and close-ups, with some tracking shots thrown in, the filmmakers include a few startling moments where the “camera” swoops or spins around the characters. These dramatic, attention-grabbing shots underline moments of action or emotion: Gen leaps into the air, in a shot that introduces the title card; Gen chases Shinji through the house; Gen and Shinji approach their parents, expecting punishment, and receive a very different response.

We also get moments where the filmmakers depart from realism to illustrate the characters’ thoughts or memories. When Gen and Shinji think about stealing the fish, we cut to a sunlight-drenched shot of the fish leaping through the air, as the boys imagine their enticing quarry. A more ominous image comes later, when Gen’s mother recalls a girl who was shot by an American plane. We see the killing unfold in a brief sequence rendered in an ultra-minimalist style, almost at the level of a line drawing, that uses just a few colors. The shift in style signals that this violence is unfolding in the character’s mind, even as the scene remains frightening and foreshadows events to come.

The second third of the movie is taken up with Hiroshima’s bombing and its aftermath, and this is when Barefoot Gen achieves the height of its power.

When we reach the morning of August 6, 1945, the movie cuts back and forth between the Nakaoka family starting their day and the Enola Gay’s flight to the city. Again, Masaki and his animators shift their style to depict the plane and its crew. The American pilots’ character design is not like that of our Japanese protagonists but has a somewhat more realistic look that resembles images from an American comic book. The different visual style emphasizes the sense that this plane represents not only a different nation but also a radically different reality that is about to intrude on the people below.

On the ground, tension builds as Gen walks to school. The skies are blue and clear, apart from the plane’s vapor trail. Gen and a schoolmate notice the plane overhead and pause to watch as sunlight flashes off it. Then the Enola Gay releases the Little Boy bomb, and for almost 20 seconds we watch it slowly fall toward Hiroshima.

To call what follows “nightmare fuel” would be an understatement. The soundtrack initially goes silent and time slows down as we witness the bomb’s effects. The flash of light briefly turns everything into a kind of photo-negative image. Windows shatter, buildings collapse. We see a series of solitary images of various city inhabitants—a child, a soldier, an old man, a mother with a baby, a dog—being incinerated. The sequence, which lasts about three minutes, ends on an animated recreation of a famous photograph taken after the bombing.

Two details from this sequence especially stick in my mind. One is how, as the mother and her baby burn up, the woman falls on top of the child in a vain attempt to save her. The other is how, as Gen and his schoolmate are hurled through the air by the explosion, we briefly see that half the schoolmate’s face has been burned away.

Scenes of the bombing’s aftermath follow, and the filmmakers pull no punches in their depiction. We see the dying and wounded. Some of them Gen first dimly glimpses walking toward him out a haze of smoke, in an image out of a zombie movie. Others we see sprawled across the cityscape in various grotesque tableaux. Some people seek haven from the fires by fleeing to the city’s rivers, only to drown there. Later, the movie doesn’t flinch from showing the grisly process of gathering and burning the bodies, nor from how the bomb’s lingering radiation affects those trying to provide aid. Amid all this suffering, Gen must deal with his own wrenching personal losses, yet still find a way to struggle on.

The fact Barefoot Gen is animated is crucial to the power of these scenes, which would not work as well if they were live action. A live-action recreation of this extreme level of death and destruction would be so gory as either to be unbearable or to risk seeming like something out of a splatter flick—or might just look fake. When done as very simple hand-drawn animation, however, all the images of burnt and bloodied dead and wounded instead have an eerie power that induces a kind of horrified silence. I was reminded of the drawings by Hiroshima survivors reproduced in the book Unforgettable Fire.

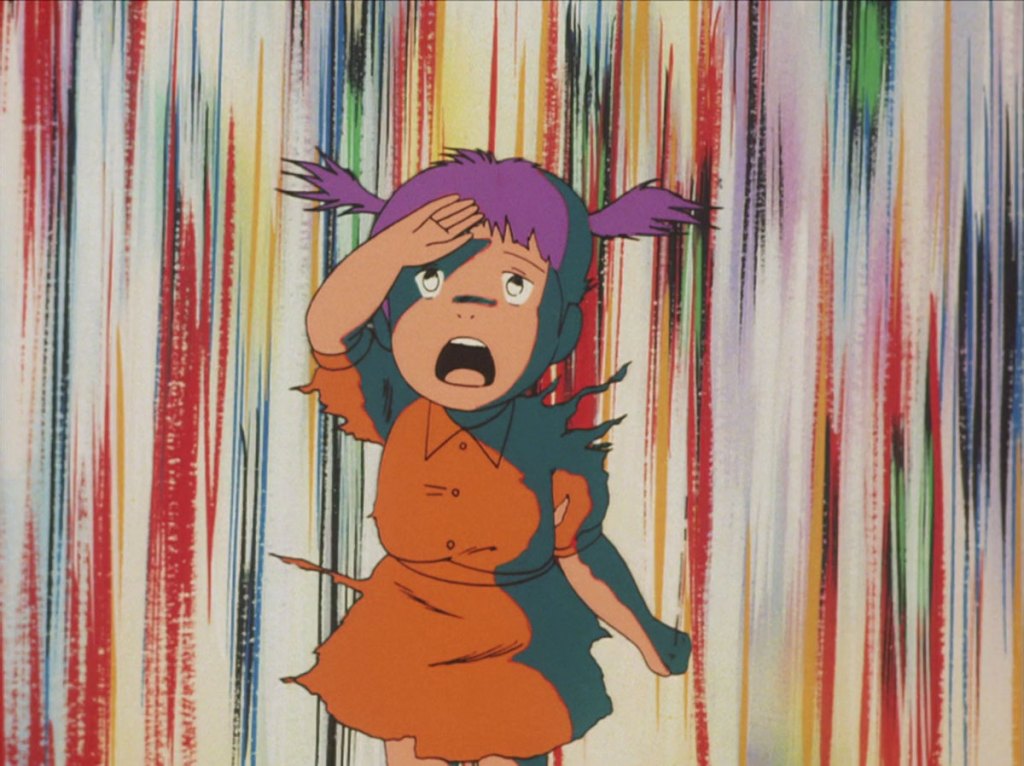

Indelible images fill this central section of the movie. During the scenes of the bombing’s aftermath, Masaki and his animators again employ the method of spinning the camera around a character to emphasize a moment: here, the circling shot is of a very young child framed against a landscape that is simply consumed in flames in every direction. Later, we get a montage of people, bowing or on their knees, listening to the emperor’s announcement of surrender over the radio—only for the montage to end in a savagely ironic contrasting image.

The movie’s final third deals with post-war life and our young hero’s attempts to survive in the remains of a war-shattered society. Here, I think Barefoot Gen stumbles. Perhaps the inevitable problem with these later scenes is that any additional events must be anti-climatic after the passages dealing with the bombing. Also, the story becomes a bit rushed. New characters, such as an urchin named Ryuta or an artist who was severely maimed by the bombing, are introduced and then have their stories resolved a bit too abruptly for them to have the intended emotional impact.

During this section of the movie, the filmmakers strain to find the right tone and veer uncertainly from grim to sentimental or even comical and back again. Sometimes this seems intentional, as when a moment of seeming triumph is undercut by a cruel loss. In general, though, the movie’s last half hour or so suffers from this inconsistency and doesn’t work as effectively as the earlier sections. However, the movie ends on the perfect note, with a scene of Gen and other characters memorializing the dead. The filmmakers once again show their visual skill, in a great final shot of Gen and the others framed against a richly colored twilight sky.

In This Corner of the World was written and directed by Sunao Katabuchi, based on a manga by Fumiyo Kono. The movie’s protagonist, a woman in her late teens named Suzu, lives in a small town close to Hiroshima. Her family harvests seaweed for a living, but Suzu is a dreamy, impractical sort who just loves drawing and painting the world around her. Some childhood vignettes early in the movie show us that her art and fantasies often seem more real to her than her actual surroundings, which frequently leads to her getting lost in her comings and goings about town.

In 1944, she consents to what is essentially an arranged marriage to a young man named Shusaku and goes to live with his family in the city of Kure, a major naval shipyard. Suzu tries to make the best of her new situation, despite the awkwardness of her relationship with Shusaku and her own difficulties adapting to life as a homemaker. Yet the ongoing war and the United States’ looming threat to the Japanese homeland eventually become inescapable for her and her family.

In This Corner of the World uses a fairly minimalist style of animation. The drawing is spare and simple: all the characters look rather small and stick-like, and their faces are often rendered as just as few lines and squiggles. The color palette tends toward light pastels that have a hazy quality and sometimes—as in a shot of the seashore at dusk—make for noticeably beautiful images. Overall, the movie has the feel of a watercolor painting done by an exceptionally skilled child; indeed, it feels just like one of Suzu’s own works.

The way the animation reflects Suzu’s view of the world is taken to an extreme in select moments where the external world and her art blur together. When Suzu, as a girl, encounters a romantic interest and paints a picture for him, the boy and the surrounding landscape become a living watercolor in her mind. Later, when her neighborhood comes under attack from American planes, the planes and bombs become a kind of living painting to her, with explosions as blotches of paint against the blue sky. Later still, at one of our heroine’s lowest points, her jagged mental state is expressed as just a series of crude chalk drawings drifting across an otherwise blank screen.

While conveying our artistic heroine’s psyche, the delicate, misty animation also perfectly fits this story’s subtlety. In contrast to Barefoot Gen, which deals in equally unabashed sentiment and horror, In This Corner of the World is a far more complex tale, about complicated relationships, where even wartime suffering is presented with a certain restraint.

The movie’s scenario of a woman in an arranged marriage, living with her in-laws, portends all kinds of domestic unhappiness and even abuse. Yet Katabuchi avoids the obvious conflicts or villains that the story might lend itself to in other hands. Shusaku is not a brute, but a decent, somewhat shy man who is kind to his wife and tries to make her happy. Suzu, while ambivalent about the marriage, welcomes his attentions and does her best to be a good wife. While sometimes strained and even stormy, their marriage isn’t miserable, either.

Shusaku’s family are similarly not portrayed as demons. His ailing parents are friendly to their daughter-in-law, despite her spaciness and lack of social graces. The one character who is initially hostile, Shusaku’s widowed sister-in-law Keiko, gradually becomes sympathetic as we learn more about her own problems and difficult family life. Meanwhile, Suzu forms a bond with Keiko’s little daughter, Harumi.

An episode about midway through the movie where Suzu’s childhood crush, now grown into a swaggering sailor, visits her household is exemplary of In This Corner of the World’s sophistication. The quasi-love triangle of Suzu, Shusaku, and the sailor could have led to a melodramatic turn in the story, but that is not what happens. All three characters deal with the situation not like characters in a soap opera but like flawed, adult human beings.

Katabuchi and his animators show great skill in their composition and staging of scenes, often hiding characters’ faces so we have to guess at their real emotions. They also inject a fair amount of humor into the story, often setting up an apparently dramatic moment only to undercut it with a comic reversal. In one scene, a character collapses in an apparent tragic turn of events, only for the reason for the collapse to be revealed as wholly innocuous. When Suzu’s drawing of the coastline gets her into trouble with the military authorities, we expect it will be an occasion for shame and anger from her in-laws. Their actual reaction is quite different and makes for a funny yet poignant moment.

Overshadowing all these familial intricacies, however, is the war, which grows into a bigger and bigger presence in our characters’ lives as Japan’s fortunes worsen. While Barefoot Gen suffers from a riveting central passage followed by an anti-climactic final chapter, the longer and more slowly paced In This Corner of the World effectively builds dramatic momentum as it moves toward its inevitable conclusion.

Early in the movie, the conflict makes its presence felt in small ways: naval operations are a constant part of life in Kure; Suzu has to help with rationing in her neighborhood; the family home is equipped with a cloth to obscure a lamp during blackouts. As 1944 turns into 1945, rationing becomes severe, American air raids become a regular part of life, and Suzu receives terrible news from her family back home.

What began as a domestic drama becomes a story of a family’s struggle to survive. A late scene, which is both sad and grotesquely funny, sums up the shift in focus. Suzu and Shusaku find themselves quarreling in the middle of an air raid, and they end up seeking shelter in a ditch even as they continue to yell at each other. In one striking shot, the feuding couple lie in the ditch, at the lower left of the frame, while the shadow of an American plane darkens the area around them. Our protagonists’ marital woes have been literally pushed to the margins by the war. (One small, touching detail of the scene is how, after Shusaku pushes Suzu down and covers her with his body, she reaches up and puts her arm around him, in an embrace.)

Three significant air attacks occur in the final section of the movie. The first is an attack on downtown Kure, which ends in a unexpected, devastating tragedy for our characters. (What happens is so abrupt and shocking that I reflexively gasped when it happened.) The second is the firebombing of the city, in which the movie’s watercolor look is turned to a more ominous use, as pale yellow lights illuminate the night sky. The third and final is of course the bombing of Hiroshima. Unlike in Barefoot Gen, we don’t actually see the bombing, but the filmmakers make the event present through a few significant, chilling details.

While they are both animated tales of family life set against the historical backdrop of World War II and the atomic bombings of Japan, Barefoot Gen and In This Corner of the World are ultimately too different for me to attempt an evaluation of which is the better movie. Barefoot Gen directly shows the bomb’s terrible consequences in their full horror, while In This Corner of the World portrays the bomb, and the larger war’s, effects more obliquely. Barefoot Gen, perhaps consistent with its child hero, evokes simple, strong feelings while In This Corner of the World, in keeping with its adult characters, deals in more complicated, nuanced emotions. In This Corner of the World is probably a more dramatically successful whole, but Barefoot Gen’s extraordinary power makes up for its flaws.

Like Isao Takahata’s masterful Grave of the Fireflies, these movies provide stunning portraits of humanity amid a great historical tragedy. All are impressive displays of what movies, and animated movies in particular, can achieve.

NOTE: Part of this post previously appeared on the blog of Rehumanize International.