Continuing with my Studio Ghibli retrospective, I turn to Porco Rosso.

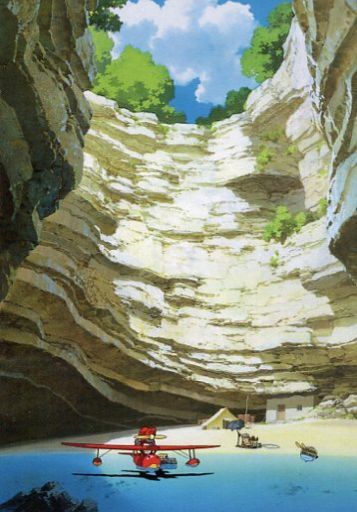

The opening shots of Porco Rosso (1992), written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki, are a masterclass in economical storytelling. We begin with a shot of a blue sky, glimpsed from within a ravine. The camera tilts down the ravine cliffs to reveal a small cove on the ground below. Moored in the waters lapping at the cove’s beach is a bright red seaplane. There’s a small encampment on the beach, and a man sleeps in a beach chair. As we get a closer look at the plane, we see that the Italian flag is painted on its tail.

The sleeper, who is dressed in a pilot’s jumpsuit, has his feet up on a table littered with cigarette butts, a bottle of wine and a wine glass, a half-eaten apple, and an old-fashioned radio playing a wistful song in French. As we cut to the first close-up of the sleeping man’s face, we see it is covered by a glossy popular magazine dated “1929.”

A phone by the man’s chair rings. Without moving much, he answers it. On the other end, we hear an anxious report: a band of seaplane pirates are trying to rob a boat carrying gold! The pilot’s services are needed! He doesn’t seem very interested, though, and gives non-committal answers. Then the caller provides some more information: the threatened boat also has a group of schoolchildren on board.

The pilot gruffly replies “It will cost you,” and rouses himself to remove the magazine from his face. At which point we see that this pilot doesn’t have a man’s face but that of a pig. The pig-man pilot then gets up and charges off to save the boat and the children on board.

So begins a bizarre but undeniably charming movie from Studio Ghibli. Our flying porcine hero, we subsequently learn, is Marco, an ace pilot who flew with the Italian air force in World War I but fled Italy after Mussolini’s rise to power. Now he makes a living along the Adriatic coast, amid the borderlands between Italy and Yugoslavia, as a bounty hunter. And somewhere along the line he was magically cursed to live as an anthropomorphic pig. His nom de guerre is “Porco Rosso”—the Crimson Pig.

Like the opening shots, the early scenes tell us much about the movie we are watching. The seaplane pirates whom Marco flies off to combat are a bunch of hairy, none-too-bright goons who do indeed kidnap the troupe of schoolgirls aboard the boat they are robbing. Rather than being frightened, however, the girls are excited by this new adventure and soon are running amok, “Ransom of Red Chief”-style, aboard their captors’ plane. When Marco engages the pirates in a dogfight, some of the girls invade the pirates’ machine-gun turret, to watch and comment on the action. Marco prevails, without anyone being so much as wounded, and retrieves the kidnapped schoolgirls and stolen gold. He leaves some gold with the pirates, though, so they can repair their damaged plane.

We thus quickly learn that this story takes place in an emphatically light-hearted, unrealistic world in which violence is mainly on the level of slapstick and dangers are not meant to be taken too seriously. This aspect of the world is reemphasized in later scenes, such as one where an unarmed, outnumbered teenager wins the respect of a huge gang of bloodthirsty thugs with a single corny speech, or one where tossing a hand grenade into a crowd causes as much actual carnage as in a Loony Toons short.

The conflict between Marco and the seaplane pirates is similarly unserious, being more like a rivalry between two schools’ sports teams than a genuine blood feud. After fighting each other, both sides retire to the area’s favored watering hole, the Café Adriano. The Café’s proprietor, the beautiful Gina, is a childhood friend of Marco’s and the widow of his best friend, who was killed in the war. Marco and Gina are clearly romantically interested in each other, but neither speaks up about it.

Meanwhile, a new arrival in town threatens to shake things up. Curtis, a dashing hot-shot American pilot, plans to challenge Marco for dominance of the skies—and win Gina’s hand in the process. In a dogfight, Curtis shoots down Marco, leaving him unharmed but crippling his plane. Marco travels to Milan to get the plane rebuilt, calling on the services of a little old engineer named Piccolo. Piccolo delegates the task to his granddaughter Fio, a bright and enthusiastic young woman with a genius for airplane design. As Fio, Piccolo, and their family work on the plane, Marco must evade the Fascist secret police, to whom he is still a dangerous fugitive.

Through it all, our hero remains the quintessential cynical, world-weary “tough guy,” unimpressed by Curtis, Fio, and pretty much anyone else he meets. He’s sort of Rick Blaine crossed with Snoopy’s World War I fighter ace persona (and, you know, a pig). In the English dub, the character is expertly voiced by Michael Keaton, who provides the necessary low, growling delivery.

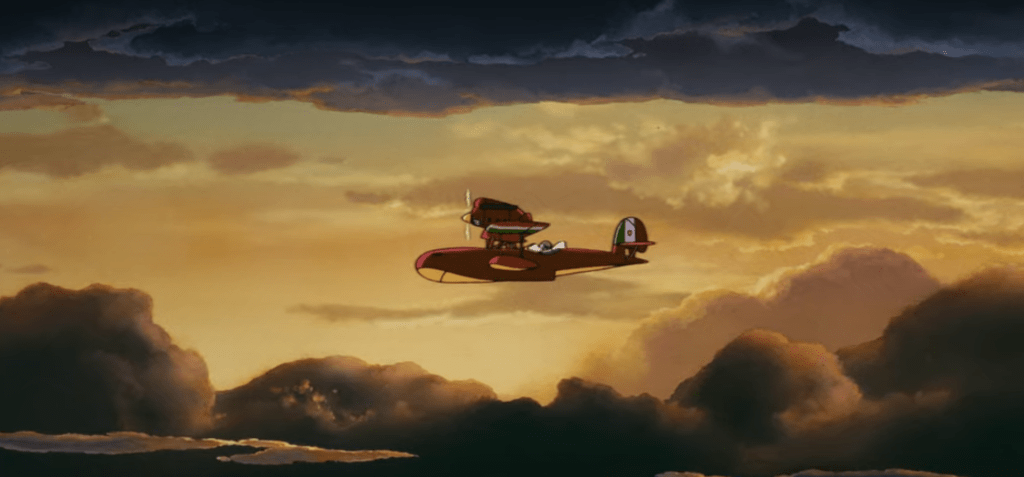

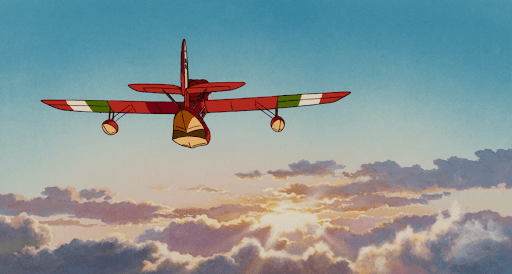

Miyazaki and his animators take full advantage of this story’s visual possibilities, giving the viewer plenty of gorgeous southern European coastal backdrops and great flying sequences. I am especially fond of how the wings of Marco’s plane flash in the sunlight. The bright red plane framed against the Milanese cityscape makes for several striking images.

While maintaining their essentially comic approach to this material, the filmmakers also hint at more serious matters. This is, after all, a tale that takes place amid the Great Depression, Fascism, and the looming specter of World War II, and Porco Rosso occasionally acknowledges these realities. Characters grouse about how little paper money is worth. When Piccolo enlists all his female relatives, including elderly women, to re-build Marco’s plane, he explains that all the men in Milan have gone elsewhere for work. Mussolini’s officials remain a recurrent danger to Marco through the movie.

Marco and Gina’s complicated relationship and history also provides an undercurrent of real emotion. Above all, though, the movie’s central grotesque conceit—Marco’s pig-man status—points toward some deeper significance. Miyazaki never explains how or why the once-human hero ended up part beast. Is Marco’s condition a metaphor for his status as a political outcast? Is it a joke about his sometimes retrograde attitudes toward women? Or does it mean something else? Porco Rosso, probably wisely, never spells it out.

Two genuinely affecting moments occur in the middle sections of the movie. The first comes when Marco flies his plane past the Café Adriano and performs aerial acrobatics for Gina’s entertainment. A brief flashback shows how the display echoes a similar episode from their youth. More than that, though, the moment shows Marco—who one doubts was very emotionally demonstrative even when fully human—expressing love in the only way he knows how.

The other moment comes when Marco tells Fio a strange, grim tale of his wartime experiences. We get a flashback to the event, which culminates in a mysterious vision of a great convoy of planes in flight. This haunting convoy is my choice for favorite image in the movie.

A favorite humanizing detail in Porco Rosso is harder to identify, perhaps because the characters and situations are generally so much larger than life. Still, I might choose one detail from the opening scene: as he dozes, Marco uses his legs to pull the table on which his feet have been propped up a little closer to him. It’s a nice bit of indolent body language.

While the movie offers some glimpses of dramatic material, that is ultimately all they are. Porco Rosso is largely a comedy-adventure, which is probably a strength. Previous Miyazaki movies have not always balanced the silly and serious so well. Despite its many good qualities, I thought Castle in the Sky suffered from the presence of the comically bumbling pirates. Here, similar characters work much better since they are more of a piece with the overall light tone. Kiki’s Delivery Service stumbled because its realistic emotional drama was at odds with the action-heavy resolution. Porco Rosso keeps its drama far more subtle and fleeting and thus its action-packed climax can be accepted more easily on its own terms. Whether the larger conflicts in Marco’s life will be resolved is kept open at the end. Even when the movie strongly implies the resolution of one issue, it is left to the audience to decide what that means.

What I think Miyazaki and his team achieved with Porco Rosso is something like what Quentin Tarantino dubbed a “hang-out movie”: a movie that you watch simply because it is fun to hang out with the characters. Marco, Gina, Fio, and Piccolo are entertaining to watch as they banter and bicker. Moreover, the movie’s beautiful settings and buoyant mood generally allowed me to set aside the serious personal and historical issues at stake and just enjoy being in this sunny, seaside world replete with pasta and red wine. This is the Ghibli movie to have on in the background some lazy afternoon—ideally while you are cooking some Italian food.

As it happened, this little gem marked the start of something of a sabbatical for Miyazaki. Having directed four feature-length animated films for Studio Ghibli between 1986 and 1992, he would now take a break from filmmaking for the next four years. At the time, fans could only hope that when he returned with a feature, it would be something memorable…

Leave a comment