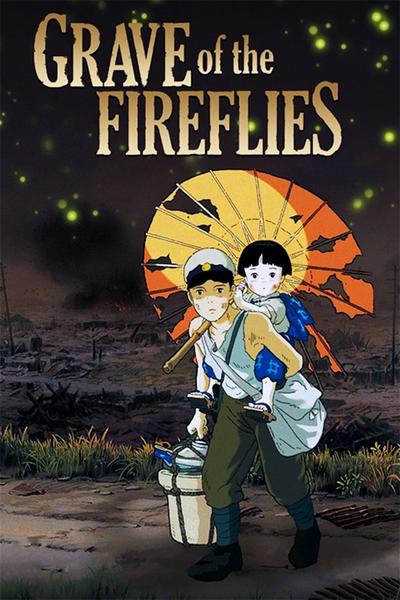

Continuing with my retrospective on Studio Ghibli films, I turn to Grave of the Fireflies (1988).

Released two years after Studio Ghibli’s debut feature Castle in Sky, Grave of the Fireflies is quite the contrast to Hayao Miyazaki’s rollicking science fiction adventure. Written and directed by Ghibli co-founder Isao Takahata, from a novel by Akiyuki Nosaka, Fireflies tells a largely naturalistic story with the simplicity of a fable. It is also one of the saddest, most haunting movies I have ever seen.

The plot is easily summarized. Set in Japan during the final six months or so of the Second World War, the movie follows a 14-year-old boy, Seita, and his 4-year-old sister, Setsuko. Their father is in the Imperial Navy and away fighting the American enemy. When the United States firebombs Seita and Setsuko’s home city of Kobe, their house is destroyed and their ailing mother is killed. The siblings briefly live with a strict aunt, but conflicts—especially about distribution of the household’s scarce, rationed food supplies—provoke them to leave the aunt and to try to fend for themselves. Seita and Setsuko live in a bomb shelter and try to survive from scavenging and using their mother’s savings. Eking out a living this way, which would be hard enough for two children under ordinary circumstances, proves impossible as the Japanese economy collapses because of the American blockade and bombing. The children succumb to malnutrition and illness and first Setsuko and then Seita eventually die.

That is Grave of the Fireflies’ story, in brief. And if, at this point in the review, you are stirring with irritation and about to complain that I just, without so much as a spoiler warning, revealed the movie’s ending, let me hasten to assure you that I have not. Nothing that happens in Grave of the Fireflies qualifies as a surprise or a twist. From the beginning, the siblings’ fate is clear. The opening scene is of Seita, reduced to begging in a train station, dying. The movie’s first line is “September 21, 1945… that was the night I died,” spoken in narration by him from beyond the grave. The rest of the movie is a series of flashbacks to the siblings’ final months. These flashbacks are interspersed with brief glimpses of Seita and Setsuko’s spirits observing their past actions as they travel to some unknown destination in the afterlife. Even the movie’s original trailer made it pretty clear this story does not end well. In short, Grave of the Fireflies is not a movie that can be “spoiled.”

Telling such a bleak tale of children perishing in a real historical tragedy is rife with potential traps for the filmmakers. I can think of two pairs of extremes that a creative team would have to steer a path between for a movie such as this one to work.

The first pair of extremes are tonal. A movie about children suffering and dying in war could go to a sentimental extreme, constantly playing up how adorable and innocent our protagonists are and how pitiable it is that these little angels must leave this world so young. Such a movie could also go to another extreme of being shocking and self-consciously “unsentimental,” piling on the horrors of wartime carnage and fatal starvation in graphic detail. Either a mawkish or gory approach could easily put off viewers through its sheer excess and induce distaste or even laughter rather than sorrow.

The second pair of extremes are of characterization. How developed should the child protagonists be as characters? If they have too little characterization, they become mere mannequins that are manipulated and tossed around from one misfortune to the next to make the point that children suffer in war. If they have highly complex characterizations, though, then the story’s focus becomes too much the struggles and relationships of these specific (fictional) people rather than the larger (real) event that they are enduring. (I think of movies such as Titanic and its many knock-offs, in which historical tragedy becomes just a backdrop for a romantic melodrama.)

For the most part, Takahata and his team find an approach to their story that avoids all these extremes. To be sure, they don’t always succeed. Grave of the Fireflies’ biggest flaw is how it sometimes veers into sentimentality: Setsuko has a rag doll that is used a few too many times to tug our heartstrings and after she dies we get a flashback montage of her playing while “Home Sweet Home” plays on the soundtrack (there is an in-movie reason for the song, but still). Seita’s unfailing patience with his sister also seems a bit too idealized; he never so much as snaps at her through all their sufferings. These minor missteps aside, however, Grave of the Fireflies does a remarkable job of finding both the right tone and the right characterization of Seita and Setsuko.

The movie’s dominant tone is neither sentimental nor lurid but rather a kind of sympathetic detachment. While we are clearly meant to be moved by Seita and Setsuko’s plight, the filmmakers nevertheless use various techniques to keep us at a distance from them. The narrative choice to reveal the children’s deaths at the start and to tell the whole story in flashback automatically replaces any element of suspense in the story with a sense of inevitability. The device of having the children’s ghosts be spectators to their own final days’ unfolding underlines the point: there is nothing to be done; just sit and watch.

This essential attitude is expressed one way or another by most of the other characters, particularly adults. After their mother is killed, helpful or villainous grown-ups are equally rare in Seita and Setsuko’s world. Their aunt is a scold and at one point an angry farmer beats up Seita for stealing from his field. Mostly, though, adults just seem indifferent or powerless. Another farmer is kind but confesses he doesn’t have any food to sell. A police officer lets Seita off the hook for stealing and even offers him some water but doesn’t do any more. A doctor diagnoses Setsuko with malnutrition but has no solution to the destitute children’s situation. Some men in town tell Seita that Japan has surrendered to the Allies and that the Imperial Fleet has been sunk (implying that their father is also now dead). When a panicked Seita asks for more news, he gets brushed off. The man who sells Seita the materials to cremate Setsuko’s body is cheerful and seemingly insensitive to the boy’s grief.

Occasionally the movie’s distance from the main characters involves a shift to other characters’ perspectives. Roughly midway through, we follow a group of school-age boys who discover Setsuko and Seita’s makeshift home in the bomb shelter. The meager provisions they find—including dried frogs, caught from the nearby river—and the boys’ resulting disgust underlines how desperate the siblings’ situation has now become. An outside perspective is taken in a still grimmer context in the movie’s opening scene. We first see passersby in the train station express scorn or pity for the dying Seita and then see station workers dispose of his body and remaining possessions. All these repeated displays of detachment or indifference reinforce the crucial point: in a country crushed by losing a war, where everyone is trying to survive, few can spare concern for two orphans.

That war’s most dramatic manifestation, the firebombing of Kobe early in the movie, offers a good example of Grave of the Fireflies’ measured approach to its bleak subject matter. We see American planes dropping firebombs as people flee for shelter; we see buildings burn; we see the burnt remains of city blocks. The filmmakers don’t linger too long over these sights, but they don’t avoid them, either: when showing the bombing’s aftermath, we get a brief but unmistakable shot of blackened human corpses lying piled up on the ground.

The movie takes more time showing us the children’s mortally wounded mother when Seita visits her at a first-aid station. The ordinary woman we briefly saw with the children at their home prior to the bombing is now a mummy, swathed in bloodstained bandages. We see, from Seita’s perspective, his mother’s bandaged face, of which only her closed eyes, part of her nose, and her withered lips are visible. Later, after she has died, we get a few very quick, blink-and-you’ll-miss-them shots of her body being taken away for cremation (including near-subliminal images of maggots crawling over her). These images are the stuff of nightmares, yet the movie soon moves on to more normal sights and situations.

These normal moments are when Seita and Setsuko try to maintain something like a routine, happy life together. Such moments make up most of Grave of the Fireflies’ middle portion and they prevent the movie from slipping too far into a relentlessly grim tone. With neither jobs nor school to occupy them, the brother and sister while away their time in various ways. They swim at the seashore, hang around in their room at their aunt’s house, and cook meals and wash dishes at their bomb-shelter home. This section of the movie includes perhaps its most famous scene, which also provides the title: the siblings gather scores of fireflies one night and release them inside the shelter, filling it with an ethereal light.

Through it all, Seita tries to keep his little sister happy with games and treats. The movie even uses this aspect of their relationship to play slightly with our expectations. One scene opens in a long shot, with Seita standing at a distance from an obviously distressed Setsuko. Has he told her about their mother’s death? No; she is upset because she cannot get the last fruit drop candies out of their tin. He gives the tin a couple good whacks and retrieves the fruit drops. Her spirits are restored.

Matching their generally successful approach to tone, Takahata and his team get the children’s characterization right. Seita and Setsuko are not truly developed characters: we don’t see them display a wide range of emotions or traits and learn next to nothing about their family or what their lives were like before the firebombing. Nevertheless, they have sufficient quirks and nuances in their behavior to provide a certain layering.

Their character design is well handled. While recognizably stylized “anime” characters, they lean closer to realism than those in Castle in the Sky or other movies. Their eyes are smaller, their faces more rounded rather than perfectly heart-shaped, and their bodies more realistically proportioned to look like those of actual 14- and 4-year-olds. Instead of the usual anime mop tops, Seita has cropped hair while Setsuko has an odd bowl cut.

The children’s body language and movement are also subtle triumphs of animation. When Seita playfully crawls on his hands and knees over to Setsuko, he does so with all the lazy insouciance of an adolescent. Setsuko demonstrates her excitement by stamping her feet, kicking, and clasping her arms to her chest in a recognizably child-like way. When she has to produce a little change purse she keeps hanging on a string around her neck, the animators have her engage in a believable amount of fumbling and false starts before she gets the purse out. When giving her fruit drops, Seita similarly has to pause to peel them off the handkerchief they have stuck to. All these little details give the characters a weight and believability.

The movie also allows them a few moments of unexpected behavior. When a melancholy Seita throws an affectionate arm over his sleeping sister, she stirs in her sleep long enough to roll away in irritation. Later, as their struggle to survive grows more dire, Seita takes advantage of the continuing American bombing raids to steal from people’s homes while they are seeking shelter. As he runs away from town, his shirt stuffed with stolen loot, a US plane flies overhead. Seita responds by fiercely punching the air in a burst of excitement: two bandits recognize each other on their respective raids. The cumulative effect of all this is to make the siblings more than mere symbols of suffering without introducing so much complexity as to be distracting.

Being animated is vital to the movie’s effectiveness. The fact the children are cartoons, suffering and dying in a cartoon world, introduces a further degree of distance and lessens both the potential soppiness and harshness of the story. We similarly don’t expect deeply textured characterization from cartoon characters as we might from flesh-and-blood characters played by live-action actors. The whole movie captures the feel of a simple but unflinching children’s book about real-life tragedy. (I was reminded of books such as Eleanor Coerr’s Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes or Junko Morimoto’s My Hiroshima.)

The Studio Ghibli animators also produce many vivid, haunting images. I have already mentioned a few of these and could probably go on for many paragraphs describing more. I will limit myself to mentioning just a few, though:

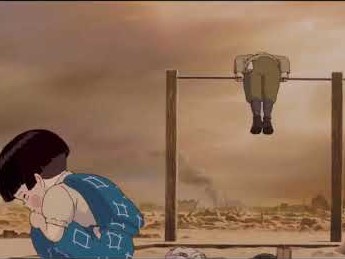

A recurring visual motif is to show Seita and Setsuko against some vast or hostile landscape, underlining their smallness in an indifferent world. Early on we see Seita carrying Setsuko across Kobe’s bombed-out cityscape. Later, the children are at the ruins of a city playground when Setsuko learns they will be separated from their mother. To distract his agitated sister, Seita does flips on the playground’s climbing bars. The filmmakers then give us a poignant long shot of the two alone in the ruins, Seita vainly doing acrobatics in the background while Setsuko, in the foreground, ignores him and cries.

Darkness is also a motif, with many scenes taking place at night or in darkened interiors. The dark also hems in and isolates the children: during the opening train station scene, Seita’s body lies in a single patch of light within the shadowy station.

Both these motifs carry through to Grave of the Fireflies’ final, powerful scene. Their story told to its bitter end, the children’s ghosts arrive at their final destination. They sit down on what appears to be a park bench. Setsuko curls up next to Seita, who says “Time for bed.” The filmmakers then cut to the movie’s final shot, a long shot of the siblings sitting alone in a park, with fireflies floating about them. As the camera tilts up, we see rising up around them one more vast panorama: the gleaming, night-time skyline of rebuilt, 1980s-era Kobe. And if your heart doesn’t break at that point, then you are made of sterner stuff than I.

Grave of the Fireflies is not an easy movie to watch and by no means for everyone. Those who do choose to watch it, though, will never forget it.

Leave a comment